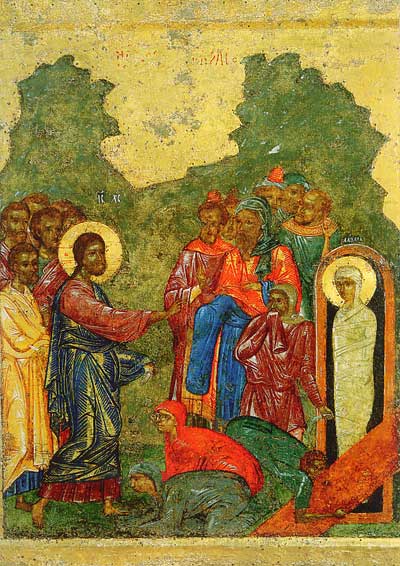

The joy that permeates and enlightens the service of Lazarus Saturday stresses one major theme: the forthcoming victory of Christ over Hades. “Hades” is the Biblical term for Death and its universal power, for inescapable darkness that swallows all life and with its shadow poisons the whole world. But now — with Lazarus’ resurrection — “death begins to tremble.” A decisive duel between Life and Death begins giving us the key to the entire liturgical mystery of Pascha. Already in the fourth century Lazarus’ Saturday was called the “announcement of Pascha.” For, indeed, it announces and anticipates the wonderful light and peace of the next — The Great — Saturday, the day of life-giving Tomb.

Lazarus, the friend of Jesus, personifies the whole of mankind and also each man, as Bethany — the home of Lazarus, — stands for the whole world — the home of man. For each man was created as a friend of God and was called to this friendship: the knowledge of God, the communion with Him, the sharing of life with Him: “in Him was Life and the Life was the light of men” (John 1:4). And yet this Friend, whom Jesus loves, whom He has created in love, is destroyed, annihilated by a power which God has not created: death. In His own world, the fruit of His love, wisdom and beauty, God encounters a power that destroys His work and annihilates His design. The world is but lamentation and sorrow, complaint and revolt. How is this possible? How did this happen? These are the questions implied in John’s slow and detailed narrative of Jesus’ progression towards the grave of His friend. And once there, Jesus wept, says the Gospel (John 11:35). Why did He weep if He knew that moments later He would call Lazarus back to life? Byzantine hymnographers fail to grasp the true meaning of these tears. “As man Thou weepest, and as God Thou raisest the one in the grave…” They arrange the actions of Christ according to His two natures: the Divine and the human. But the Orthodox Church teaches that all the actions of Christ are both Divine and human, are actions of the one and same person, the Incarnate Son of God. He who weeps is not only man but also God, and He who calls Lazarus out of the grave is not God alone but also man. And He weeps because He contemplates the miserable state of the world, created by God, and the miserable state of man, the king of creation… “It stinketh,” say the Jews trying to prevent Jesus from approaching the corps, and this “it stinketh” can be applied to the whole of creation. God is Life and He called the man into this Divine reality of life and “he stinketh.” At the grave of Lazarus Jesus encounters Death — the power of sin and destruction, of hatred and despair. He meets the enemy of God. And we who follow Him are now introduced into the very heart of this hour of Jesus, the hour, which He so often mentioned. The forthcoming darkness of the Cross, its necessity, its universal meaning, all this is given in the shortest verse of the Gospel — “and Jesus wept.”

We understand now that it is because He wept, i.e., loved His friend Lazarus and had pity on him, that He had the power of restoring life to him. The power of Resurrection is not a Divine “power in itself’,” but the power of love, or rather, love as power. God is Love, and it is love that creates life; it is love that weeps at the grave and it is, therefore, love that restores life… This is the meaning of these Divine tears. They are tears of love and, therefore, in them is the power of life. Love, which is the foundation of life and its source, is at work again recreating, redeeming, restoring the darkened life of man: “Lazarus, come forth!” And this is why Lazarus Saturday is the real beginning of both: the Cross, as the supreme sacrifice of love, and the Common Resurrection, as the ultimate triumph of love.

“Christ — the Joy, Truth, Light and the Life of all and the resurrection of the world, in His love appeared to those on earth and was the image of Resurrection, granting to all Divine forgiveness.”