No book on the history of the Russian Church in the twentieth century can be complete without including the name of St. Athanasius (Sakharov), Bishop of Kovrov, a catacomb bishop who reunited with the Moscow Patriarchate in 1945. We will not, however, discuss the historical events in which he participated, but rather how holiness exists in time – all the more so, since we are considering the twentieth century, which is nearly contemporary.

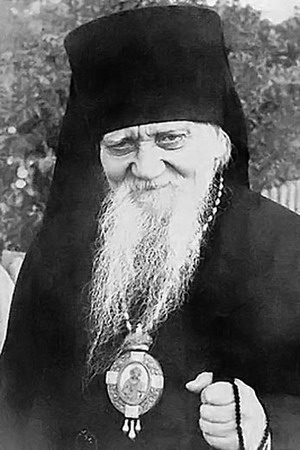

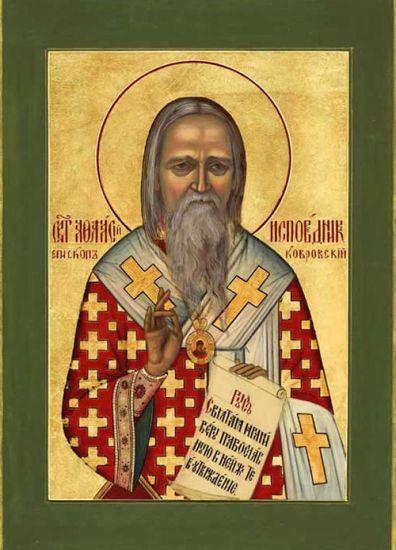

Icon of St. Athanasius (Sakharov) the Confessor, Bishop of Kovrov. The icon was painted in 2006 for the Church of the Protection of the Theotokos in the Butyrskaya prison from donations from the parishioners of the St. Nicholas Church in Biryulyovo.

Almost Our Contemporaries

The beginning of the Church-wide veneration of the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia allowed us the entirely unique experience of witnessing the attainment of holiness. Not long ago, our lives were separated from the earthly lives of the saints by centuries. While reading about early Christian martyrs, the temporal distance deprived us of the ability to relive their struggles. In the lives of the saints we studied historical details, searching for moral lessons while enjoying the exquisite style of Byzantine hagiography. We could not do one thing: experience for ourselves the fear and pain of a person thrown into an arena teeming with wild beasts.

It has been centuries since people forgot how to read the lives of saints as eyewitness accounts. Not incidentally, literary historians have noted a fundamental abstraction in hagiography and the refusal of authors to specify historical details. D.S. Likhachev[1] once pointed out that the authors of the lives of Russian saints wrote descriptively and without political terminology about very specific details. Instead of “burgomaster” [posadnik] they wrote of “a certain nobleman” or of “an elder,” and instead of “Prince,” they wrote of “a ruler of that land.” The names of episodic characters were eliminated and replaced with the descriptive “a man,” “a certain maiden,” etc. In practice, glorification by the Russian Orthodox Church took place after a considerable time. However, the glorification of the New Martyrs and Confessors made it impossible to leave out historical specificity.The new saints are practically our contemporaries. They are the contemporaries of our grandparents or great-grandparents, and so their lives belong to a time we know about not only from books, but also from the stories of our older generations. In these accounts, the abstract words “ruler of the city” cannot appear, simply because the portraits of these rulers hung in the schools our parents attended. And children with red scarves [i.e., Young Pioneers], whose descendants we are, brought these rulers flowers on the anniversaries of the revolution.

An Unnoticed Revolution

The difference between the approach of historians and hagiographers is well known. The historian describes the life of a person, his biography, while the hagiographer writes a description of his holiness. The short span of time separating us from the New Martyrs allows us the opportunity to see this difference.

Sergei Sakharov was born into a family with a traditional, provincial way of life. As a child he went to church joyously and was very fond of solemn hierarchal church services, and at home played “church” in bishop’s robes constructed from his mother’s shawl; he imitated the service, by censing, blessing, and so on. As he matured he had the ability to bypass, and perhaps even to ignore, the temptations of his times. Very indicative in this respect are the years the saint spent studying at the seminary in Vladimir. His memories of seminary life were always very warm. An historian, however, might reconstruct the seminary life of those years as anything but idyllic.

Here are the memories of seminary life in Vladimir of Metropolitan Evlogy (Georgievsky), who was a supervisor there from 1895 to 1897: “I took vodka away from the seminarians and reprimanded them severely, though not publically. While moving tables, the caretaker of the diocesan dormitory found a forged bottom shelf (an armful of banned books fell out of it), and I investigated the matter privately. It happened that sometimes in the evening I would go around the dormitories and suddenly hear, ‘Oh, what if I slipped you an ace!’ Obviously, the seminarians were quietly playing cards. I broke the silence: ‘Yes, yes, good move!’ Confusion then followed.”

In 1903, when the future saint studied there, the seminary in Vladimir had a secret cell of the Social Democratic Party, which broke up after one of its organizers was killed by the careless handling of explosives. An underground seminary congress gathered there in the summer of 1905. In December of the same year the seminarians went on strike.

Characteristically, Sergei Sakharov, who was a witness of these events, did not talk about them at all. One gets the impression that social life and political passions did not particularly interest him. Remembering his seminary years, he often spoke of Archbishop Nicholas (Nalimov) of Vladimir, a strict ascetic who was an expert on the divine services. It seems that the rest passed by unnoticed and did not have much significance for the saint.

After seminary he studied at the Moscow Theological Academy (here Sergei Sakharov was tonsured a monk with the name of Athanasius). He also taught and participated in the Local Council, after which the monk Athanasius returned to the Vladimir Diocese.

“We Need Not Fear Prison…”

He became a bishop in 1921. Before his consecration to the episcopacy the future hierarch was summoned to the GPU[2] and threatened with repression if he agreed to become a bishop. Before the Revolution, being a bishop meant having many significant social benefits, but by 1920 a hierarch was guaranteed persecution and deprivation.

St. Athanasius was arrested for the first time just seven months after his consecration. By his own count, over the years he spent only two years, nine months, and two days in diocesan service, yet “in bonds and bitter work” (i.e., prison and exile) he spent twenty-one years, eleven months, and twelve days.

We know much about prisoner life. In reading the letters of St. Athanasius from the camps and the memories of people who saw him there, one is struck by his incredible ability to ignore the inhumane living conditions and by his strength to remain a monk in the face of it all.

Here is an excerpt from a letter to his mother from the Taganskaya prison, where he was awaiting exile: “Now I see here bishops and priests who are in prison for Christ. I hear about Orthodox pastors in other prisons who are all complacent and calm. <…> We need not fear prison. It is better to be here than to be free, and I am not exaggerating. Here is the true Orthodox Church. We are inside as if in isolation during an epidemic, though we do experience some restriction. Yet how many sorrows you have! <…> Constantly waiting to be called to visit those whom you do not want to visit. <…> And trying to stand firm. We are almost guaranteed not to experience this. So when I receive condolences on my present situation, I am very embarrassed. The plight of free Orthodox Christians that carry the banner of Orthodoxy is much greater. Help them, O Lord.”

His letters from camp resemble those of a pilgrim writing from a distant monastery. Here is his description of a 1940 Nativity service held in a shack on bunks in the White Sea-Baltic Canal (Belomorcanal) camp and of his visit to the graves of people close to him: “This night, with some breaks (I fell asleep … woe to lazy me…) I served a festive vigil. After the service I went to glorify the newly-born Christ at the graves of the departed and the cells of the living. Here and there I sang the festal troparion and kontakion, then the augmented litany, changing only one petition, and then the special dismissal, after which I congratulated the living and departed, ‘all ye for Him are still alive.’ As if I saw everyone and was comforted by collective prayer. And how many places I visited spiritually… I started, of course, with the grave of my sweet mother, and then visited my father, my Godmother, and then traveled around Holy Russia, first to Petushki, and then to Vladimir, Moscow, Kovrovo, Bogolyubovo, Sobinka, Orekhovo, Sergiev, Romanov-Borisoglebsk, Yaroslavl, Rybinsk, St. Petersburg, and then to places of exile: Kem, Ust-Sysol’sk, Turukhansk, Yeniseisk, Krasnoyarsk…”

To comment on this “Christmas portrait,” it should be added that this letter was written by a fifty-one-year-old man with heart disease, who could barely breath when walking, but had to walk daily five kilometers to his workplace. The work consisted of unloading firewood, logging, snow removal, and more. Any Church-related items were not permitted in camp. Everything was taken away, not only books but even a hand-painted Easter egg received by mail. Despite official permission for imprisoned priests to keep their long hair, the hierarch was forced to cut his hair.

In some camps the prisoners were allowed to have books. Here is how E.V. Apushkina describes the arrival of Hieromonk Hierax (Bocharov) to the Mariinsky Camp in 1944: “The door opened. There was the sound of rolling dice, swear words, and prison jargon. The air was blue with smoke. The rifleman nudged Fr. Hierax and pointed out his bunk. The door slammed shut. Stunned, Fr. Hierax stood at the doorstep. Someone said to him: ‘Go over there!’ Going in the indicated direction, he stopped at an unexpected sight. On the lower bunk, his legs tucked up, surrounded by books, sat Bishop Athanasius. When he raised his eyes and saw Fr. Hierax, whom he knew, His Grace was not surprised and did not greet him, but simply said: ‘Read! Tone such-and-such, troparion such-and such!’ ‘Can we read here?’ ‘Yes we can, we can! Read!’ Continuing the service with the bishop, Fr. Hierax noticed that all anxiety and all heaviness that had been pressing on his soul were immediately gone.”

“Prayer Will Save You All…”

The retired bishop spent the last years of his life in the city of Petushki, Vladimir region. He was denied political rehabilitation. During the Khrushchev period former Soviet party functionaries arrested during the purges were politically rehabilitated. Church leaders were still considered enemies of the people, so the authorities did not question the correctness of their condemnation.

St. Athanasius spent the remainder of his life after his return from the camps in Petushki. The house where the saint reposed has been preserved. Pious parishioners turned this house into a small museum. In the room are his personal items: a bed, desk, icons, embroidered vestments, and a wooden Panagia, carved and painted by him.

In 1958, the prosecutor of the Vladimir region wrote that since Bishop Athanasius had for over thirty years not concealed that he was “a believer and servant of the Church, and so could not agree with the atheistic authorities in matters of religious views and worship,” his sentence was therefore fair and there was no reason for rehabilitation.[3]

The bishop, during his last years, could serve only at home in his cell – which had its advantages, not only because of the widespread reduction of church services, which greatly distressed Bishop Athanasius, but because only in his cell could he pray before icons of the last Tsar and his family and of Patriarch Tikhon, both of whom he greatly venerated. Only where the saint was devoid of prying eyes could he strictly fast and pray for Russia each year on November 7 and 8(Soviet holidays dedicated to the October Revolution).

The saint’s forced isolation was not reclusion. He kept up correspondence with spiritual children and people continually came to him with their questions and problems. Church historian M. E. Gubonin,[4] who visited Bishop Athanasius in 1958, compared the hierarch with the bishops exiled during the Ecumenical Councils. He wrote: “Looking at him you can vividly imagine that remote epoch of dogmatic and iconoclastic troubles in Byzantium, when young hierarchs and monks, zealots for pure Orthodoxy, were exiled and forgotten by all, and after decades had passed they stood before the eyes of the younger generation like people from another world, gray-haired and with trembling hands, but with an unconquerable, strong spirit still blazing with the flame of their unshakable faith in the beliefs to which they so readily sacrificed their oppressive exilic life.”

St. Athanasius died on October 28, 1962. His last words were “Prayer will save you all!” He was buried in the cemetery of the Presentation in Vladimir, adjacent to the barbed wire fence of the Vladimir prison that he repeatedly had to visit. After his glorification in the autumn of 2000, the saint’s relics were transferred to the Monastery of the Nativity of the Mother of God, of which he had been superior in 1920. For a long time the monastery housed the Vladimir Cheka.[5] The procession with the relics went along the same path that Bishop Athanasius followed when led from prison for interrogation.

The Right for An Anachronism

Here we are attempting to speak of a saint, not of a historical figure. Therefore, we do not write about St. Athanasius’ participation in the Local Council of 1917-1918, nor about his struggles against the Renovationists,[6] nor about his break with Metropolitan Sergei (Stragorodsky),[7] and then, after the Second World War, his reunification with the Moscow Patriarchate, nor of his many years as a corrector of liturgical books. We are not interested in him as an historical person, but rather in how sanctity triumphs over historical time.

The phenomenon of the New Martyrs began to be understood only in the 1960s (in 1981 the New Martyrs of Russia were glorified by ROCOR and in 2000 by the Moscow Patriarchate). But the words “New Martyr” first appeared in documents of the Local Council of 1917-1918, when no political analyst could possibly have predicted the scale of church persecution. In 1918, St. Athanasius, together with Professor B. A. Tourayev,[8] was commissioned by the Local Council to compose the “Service to All Saints of the Russian Land,” which included this troparian to the New Martyrs:

O ye holy hierarchs, royal passion-bearers and pastors,

monks and laymen, ye countless new-martyrs and confessors,

men, women and children, flowers of the spiritual meadow of Russia,

who blossomed forth wondrously in time of grievous persecutions,

bearing good fruit for Christ in your endurance:

Entreat Him, as the One that planted you,

that He deliver His people from godless and evil men,

and that the Church of Russia be made steadfast

through your blood and suffering,

unto the salvation of our souls.

When these troparia were being written, the Bolshevik war against the Russian Church was just beginning and few believed that this persecution would only increase. An historian analyzing the trends of these times might say that things could have evolved differently. Yet holiness is a victory over time and the holy hagiographer can afford to write what the historian would call an anachronism.

[1] Dmitry Sergeyevich Likhachov (November 28 [O.S. November 15], 1906, St. Petersburg – September 30, 1999, St. Petersburg) was an outstanding scholar who was considered the world’s foremost expert in Old Russian language and literature. He has been revered as “the last of old St Petersburgians,” “a guardian of national culture,” and “Russia’s conscience.”

[2] The State Political Directorate was the secret police of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1934. Formed from the Cheka, the original Russian state security organization, on February 6, 1922, it was initially known under the Russian abbreviation GPU–short for “Gosudarstvennoye Politicheskoye Upravlenie of the NKVD of the RSFSR” (Государственное Политическое Управление НКВД РСФСР). Its first chief was the Cheka’s former chairman, Felix Dzerzhinsky.

[3] Rehabilitation (Russian: реабилитация, transliterated in English as reabilitatsiya or reabilitacija) in the context of the former Soviet Union, and the Post-Soviet states, was the restoration of a person who was criminally prosecuted without due basis to the state of acquittal.

[4] Mikhail Efimovich Gubonin (June 24, 1907 Moscow province – October 9, 1971 Moscow) — Russian artist, church historian, archivist, author of several literary works.

[5] Cheka (Chrezvychaynaya Komissiya, Extraordinary Commission) was the first of a succession of Soviet state security organizations. It was created by decree on December 20, 1917, by Vladimir Lenin and subsequently led by aristocrat-turned-communist Felix Dzerzhinsky. After 1922, the Cheka underwent a series of reorganizations into bodies whose members continued to be referred to as “Chekisty” (Chekists) until the late 1980s.

[6] The Renovationist Church (Russian: Obnovlencheskaya Tserkov), a reform movement supported by the Soviet government, was a federation of several reformist church groups that took over the central administration of the Russian Orthodox church in 1922 and for over two decades controlled many religious institutions in the Soviet Union.

[7] Seeking to convince Soviet authorities to stop the campaign of terror and persecution against the Church, Metropolitan Sergei sought means of peaceful reconciliation with the government. On July 29, 1927, he issued his infamous Declaration, in which he professed the absolute loyalty of the Russian Orthodox Church to the Soviet Union and to its government’s interests. The Declaration, albeit well intentioned, sparked immediate controversy among Russian churchmen, many of whom (including many notable and respected bishops in prisons and exile) broke communion with Sergei. Later, some of these bishops reconciled with him, but St. Athanasius and many other bishops remained in opposition to the “official Church” until the election of Patriarch Alexei I in 1945.

[8] Boris Aleksandrovich Turaev (Born July 24 [Aug. 5 O.S.], 1868 – July 23, 1920, in Petrograd (St. Petersburg). Russian Orientalist. Founder of the Russian school of the history and philology of the ancient East. Seminal figure in Russian Egyptology and Ethiopian studies. Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences (1918; corresponding member, 1913).

Translated from Russian by Sophia Moshura.