A small group of a dozen or so young medical professionals were sitting around a table, munching cookies and downing soft drinks. They were all mainline Protestants or Evangelicals. Some were very much connected to their church tradition; others were thirsting for something else, which clearly meant something more. They had asked us to come and talk about Orthodoxy. Most of them had never been to an Orthodox worship service, and they were as curious as they were welcoming. Overall, the atmosphere was warm and cordial.

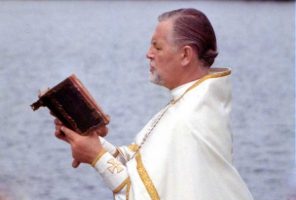

They raised the usual question: “What’s the difference between your faith and ours, between the Orthodox and, say, Baptists?” Several of them had asked this kind of question to other Orthodox Christians, only to receive confusing and unsatisfying answers. Both priests and laypeople had given them the impression that the differences concerned either “things”—ecclesiastical trappings—or dogmas, usually wrapped up in obscure theological jargon. They had pointed to vestments, fasting, long services, incense, icons, and cupolas. Some had stressed the importance (and unavailability to the “heterodox”) of Communion and Confession. Others had talked in more theological terms of the Orthodox view of the papacy and of the “filioque” clause added to the Nicene Creed. A few had focused on the interpretation of Romans 5:12 and the “transmission” of sin and guilt. And nearly all of them had denounced the “Protestant” notion of “Once saved, always saved,” while they belittled long sermons, revivals and social activism.

People in the group looked at us and wanted to know if there wasn’t more to it than that. For over two hours we exchanged thoughts about our respective beliefs and traditions. Finally we parted with warm handshakes, while a few asked if we could continue with this kind of exchange.

At home later that evening, I picked up the local paper and turned to the Religion section (a popular feature in Charleston, the “Holy City”). One column offered thoughts of two clergymen on the question of “miracle healings.” What should a sick person do to receive one? An answer, provided by the pastor of the “Unity Temple on the Plaza” in Kansas City, contained an admission—a virtual confession of faith—that made me realize how inadequate my answers had been to questions raised earlier in the evening about the differences between Orthodoxy and other traditions. While most Protestants would not agree with this pastor’s remarks, they are nevertheless representative of an overall attitude widespread in America’s post-Christian culture.

“I don’t believe that God intervenes in our lives,” the good cleric wrote, “but I do believe that God Spirit [sic] is in every one of us, and the more we awaken to that power, the more we are able to utilize it for physical, emotional and mental healing.” It reminded me of experiments recently undertaken by an atheistic professor at Harvard’s medical school, to determine the usefulness of prayer for healing various illnesses.

What are the chief differences between Orthodoxy and other expressions of religious or, more specifically, Christian faith? It would take far more space than is available here to begin an adequate reply. There is one thing, though, that is too seldom talked about, yet seems to be among the most significant differences. That is the matter of perspective, of a world-view that beholds the presence, purpose and power of a loving and compassionate God, in all of creation and in every aspect of our personal life and experience. What does this mean for us and for our “life in Christ”?

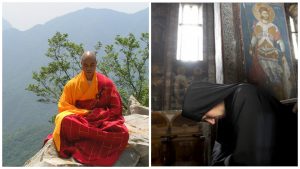

Orthodox spiritual elders have often made the point that the uniqueness of Orthodoxy lies in its call to holiness: to a thoroughgoing transformation of the human person that leads to “the likeness of God.” God intends that our life be a pilgrimage, an extraordinary adventure, that can lead progressively through stages of growth known in the monastic tradition as “purification,” “illumination” and finally “deification”: a real and eternal participation in the Life of the Holy Trinity. A quest for the “likeness” of God is a quest to be holy as our heavenly Father is holy, to strive not for our own perfection, but for His. It is to allow the Holy Spirit to re-create us in the Divine Image, to lead us from a self-centered state of sinfulness, corruption and death to one of righteousness, peace and joy, as we dwell in eternal and intimate communion with the Lord of all things.

Our Protestant colleagues are right: we can never make that kind of pilgrimage on our own. We can never attain holiness, never achieve sanctity, through our own actions or merits. Call it “salvation,” or call it a quest for theosis or “deification.” In any case, the possibility and initiative lie wholly in the hands of God. If there is sanctification in this life, if there is any realistic hope for sharing in “eternal glory,” it comes as a pure, undeserved and unearned gift.

In Orthodox experience, however, that gift is communicated to us in very specific ways, ordained by God Himself. These include entering into and making our own the Faith of our Fathers: the convictions about God and the human person that led many of those Fathers to sacrifice their lives rather than compromise their beliefs. They include active participation in the Body of Christ: its worship, its sacraments, and its self-giving service to God’s world. This means that everything from vestments and incense to particular doctrinal positions have their place and their significance. Yet all “things,” like all dogmas, serve a higher end. They serve our life and our growth, our pilgrimage, which leads toward the holiness that only God embodies and can convey.

The next time I share cookies and Coke with these Protestant friends, I hope I’ll remember to begin and end where Orthodoxy itself begins and ends: with the notion of pilgrimage, of transformation and endless growth in the Spirit. Bishop Kallistos Ware began his marvelous little book The Orthodox Way with the story of an old woman who lived as a recluse in Rome. Asked by St Serapion why she spent her time just sitting in her room, she replied, “I am not sitting. I am on a journey.”

If we are to behold the presence and power of God in our life and in all creation, it can only be by embarking on just that kind of journey. For those who do—who take up, with faith and love, an ardent quest for holiness—their very life reveals the most significant differences that set Orthodoxy apart from other expressions of faith (including “nominal Orthodoxy”). Their life becomes a powerful witness that draws others into the same pilgrimage, the same adventure of faith and love, that they themselves are on. And more than the splendor of vestments or the beauty of liturgical music, more than any persuasive arguments about doctrine and ecclesial praxis, that witness will lead others to move beyond “the differences” and toward an appreciation of Orthodoxy in its essence and at its heart.