Not many of the faithful know much about this feast. Apart from the clergy and a few lay people who have close ties to the Church, many don’t even know of its existence. Few attend church on the day and most people have no inkling that, on the Wednesday after the Sunday of the Paralytic, the Church celebrates a great feast of the Lord, that of Mid-Pentecost. And yet, at one time, this feast was celebrated on a grand scale in the Great Church of Constantinople and was attended by large numbers of people.

All you need to do is to open the Έκθεσις περί της βασιλείου τάξεως (‘Treatise on the order of ceremonies of the realm’, usually ‘On Ceremonies’) by Emperor Constantine Porphyrogennitus to see the formal order of service for the feast, as it was celebrated until Mid-Pentecost in the year 903 in the church of Saint Mokios in Constantinople. In other words, until the day of the assassination attempt against Emperor Leo VI, the Wise (11 May, 903). This contains a detailed description of the magnificent order of service, which takes up numerous pages in the text, and, in the well-known strange Byzantine terminology, defines how, on the morning of the feast, the emperor would set out in his official imperial garb. Accompanied by his retinue, he would leave the royal palace and head for the church of Saint Mokios, where the divine liturgy was to be celebrated.

Soon afterwards a procession arrived headed by the patriarch*. Emperor and patriarch would then have entered the church in a show of great pomp. The divine liturgy was celebrated with all the usual magnificence of Byzantine festivals. After the dismissal, the emperor hosted a breakfast at which the patriarch was chief guest. With the multitudes crying aloud ‘May God bring your reign many and prosperous years’ and with many intermediate stops along the route, the emperor returned to the royal palace.

And in today’s liturgical books, too, in the Pentikostario, we can see traces of the old grandeur. The day is presented as being a great feast of the Lord: with its wonderful hymns and double canons, works of the great hymnographers Theofanis and Andrew of Crete; with the readings; with the influences of the preceding and following Sundays; and with the extension of the feast for eight days, in accordance with the rule for the great feasts of the Church year.

But what is the theme of this unique feast? Not any great event in the Gospel story. The subject is entirely festal and theoretical. The Wednesday of Mid-Pentecost is the 25th day after Easter and the 25th day before Pentecost. It marks the mid-way point in the fifty days of celebration which follow Easter. In other words, it’s a stage, a dividing-line.

So, without having its own special theme, the day is associated with the events of Easter on the one hand and the descent of the Holy Spirit on the other. It also adumbrates the glory of the Lord’s ascension, which will be celebrated in a fortnight. Precisely because it is in the middle, between the two great feasts, it brings to mind a Hebrew epithet for the Lord ‘Messiah’, which was translated into Greek as ‘Christ’. But the sound of ‘Messiah’ is reminiscent of ‘middle’ [as it would be in English if we called the feast Meso-Pentecost]. Thus, in the hymns and synaxario, this false etymology is exploited to present Christ as the Messiah- the mediator between God and humankind: ‘our mediator and reconciler with his eternal Father’. Nikiforos Xanthopoulos notes in the synaxario: ‘For this reason we celebrate the present feast, calling it Meso-Pentecost and we hymn Christ the Messiah’.

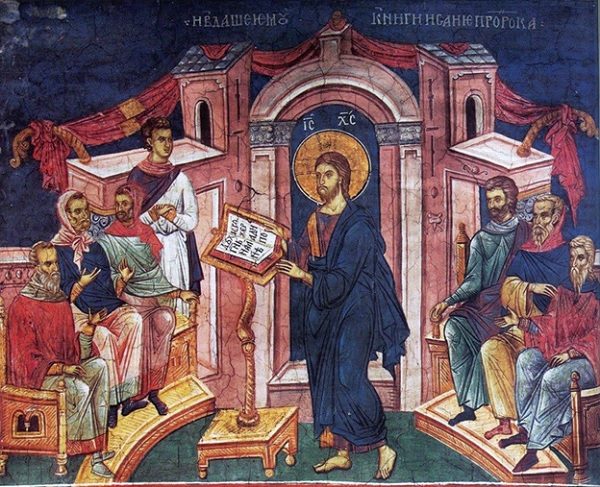

Contributing to this is the Gospel reading selected for the day. About the middle of the Jewish feast of the Passover, Christ went up into the temple and taught. His teaching aroused admiration, but also lively dispute between him and the people and the teachers. Is Jesus the Messiah or not? Is his teaching from God or not? Now a new issue was added: Jesus was the Teacher. Although he not had any education, he had the fullness of wisdom, because he was the Wisdom of God, who created the world. It is from this dialogue that many of the hymns for the feast derive. He who taught in the temple, in the midst [meso-] of the teachers of the Jewish people, at the mid-point [meso-] of the feast is the Messiah, the Christ, the Word of God. He who was derided by the allegedly wise men of his people, is, in fact, the Wisdom of God.

A few lines further down in the Gospel of Saint John, immediately after the excerpt containing the Lord’s dialogue with the Jews ‘at the middle of the feast’, there comes a similar dialogue between Christ and the Jews ‘on the last day of the great feast’, that is Pentecost. It begins with the Lord saying: ‘Let anyone who is thirsty come to me and drink. Whoever believes in me, as Scripture has said, rivers of living water will flow from within them’. And the Evangelists comments ‘By this he meant the Spirit, whom those who believed in him were later to receive’.

It’s of no significance that these words of the Lord weren’t spoken at Mid-Pentecost but a few days later. By poetic licence they are put into the mouth of the Lord in his homily at Mid-Pentecost. In any case, they’re so fitting as regards the theme of the feast. No more apt image could be found to show the nature of Christ’s teaching work. The teaching of the Lord came to the thirsting human race like living water, like a river of grace cooling the face of the earth.

Christ is the source of grace, ‘of water welling up to eternal life’ which slakes and waters the souls of people ceaselessly tormented by thirst. Which transforms those who drink into springs: ‘rivers of living water will flow from within them’. ‘And it will become in them a spring of water welling up to eternal life’, as the Lord said to the Samaritan woman. It has transformed the wilderness of this world into a divinely-established paradise of evergreen trees planted by the streams of the waters of the Holy Spirit. This fertile theme provided fresh inspiration for ecclesiastical poetry and adorned the feast of Mid-Pentecost with exceptionally beautiful hymns.

This, briefly is the feast of Mid-Pentecost. Lack of any historical foundation has deprived it of the folk character necessary to make it popular with most people. And its entirely theoretical theme is of no help to Christians lacking the theological requirements to see through the surface and delve into the fêted glory of Christ the Teacher, of the Wisdom and Word of God, of the source of never-failing water. Something similar has occurred in the case of churches dedicated to the Wisdom of God. Instead of honoring the name of Christ as the Wisdom of God, to whom they were dedicated when they were built, they now normally celebrate the feast of Pentecost, or the Holy Spirit, or the Holy Trinity, or the Entry or Dormition of the Mother of God. Or even the martyr Saint Sophia and her three daughters, Faith, Hope and Charity**.