Egyptian President Mohammed Mursi assumed office on June 20, 2012. Mursi represents the pan-Islamic Muslim Brotherhood, which is recognized in a number of countries (including Russia) as extremist. Forecasts of a radical Islamization of Egypt do not therefore appear to be unfounded. Due to the strong inter-confessional conflicts that accompanied the revolution in Egypt, this development could endanger the peaceful and prosperous existence of Coptic Christians, who make up the second largest religious group in the country. Contrary to expectations, however, the first civilian president of Egypt announced even before his inauguration that he would appoint a Christian as one of his deputies.

Are Egyptian Christians in danger? What are Mursi’s prospects? Will peace return to Egypt? Alexander Shumilin, director of the Center for the Analysis of Middle East Conflicts at the Institute for U.S. and Canadian Studies at the Russian Academy of Sciences, and Konstantin Eggert, international journalist and radio commentator for Kommersant FM, respond to these questions.

Alexander Shumilin: Mursi’s mission is to pacify radicals and extremists

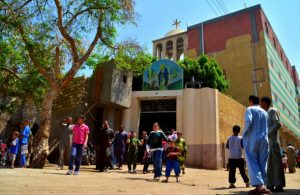

Egypt’s Coptic Christian community is quite large, constituting 10% to 15% of the country’s population. This community is an integral part of Egypt and its history. In Cairo there is a cathedral on the location where, according to tradition, the Holy Family found refuge during Herod’s persecution. On the territory of Cairo in general there are quite a few churches, which form part of the city’s landscape.

Stable relations between Copts and Muslims are the key to social peace in Egypt, while interaction between the two communities is the key to the country’s progress.

President Mursi will therefore appoint a Copt as his deputy and a woman as his second vice-president. This decision should not be the cause of criticism from his supporters: the Islamists have already won, gaining the upper hand, and will show mercy and understanding. This is precisely Mursi’s mission in Egypt’s Muslim community: to pacify radicals and extremists.

If Muslims, especially the militaristically minded, had previously seen the Copts as enemies, or at least as rivals, they now nonetheless have grounds to accept them – even if they are adherents of a different faith – as fellow citizens who are at a disadvantage. Finishing off the vanquished is not only looked down upon in every religion, but it is simply inhumane and amoral.

It goes without saying that this combination – Mursi as Islamist president with two vice presidents, one Copt and the other a woman – is compatible with Egypt’s Supreme Military Council. The generals have maintained a significant amount of power in order to keep the balance and not allow the country to slide into radical Islamism.

This past presidential election was the first such experiment in Egyptian society. The winner should understand that he is not the absolute winner, as is evidenced by the minimal margin of votes between candidates. Mursi understands this, which is why he is taking such steps.

It is important that the democratic election process is gradually becoming established in Egypt, moreover with the Supreme Military Council overseeing the development of democratic mechanisms. Mursi took an oath on the country’s constitution to observe it and other rules of democratic order during his presidential term.

The defeated have the chance to take revenge during the next election cycle and attempt to bring to power a different kind of policy and ideology – but most likely not another religious faith.

Konstantin Eggert: Egypt’s best option is to follow the Turkish model

So far the new Egyptian president’s public statements encourage optimism. His affirmation that Egypt will remain a secular government and that he will appoint a Copt and a woman as deputies is of great symbolic importance. Mursi is indeed not very radical. He studied in the United States. One can conclude from the news coming from Egypt that he has reached some sort of mutual understanding with the army. Following the transfer of power from the Supreme Military Council to the president, Field Marshal Mohamed Tantawi will be named minister of defense. Which means that the army will in fact retain the position it had under President Murbarak.

Today one can confidently say that the Muslim Brotherhood has no chance of taking full power in Egypt; and, most likely, if the chance does arise it will be no time soon. The elections demonstrated that the country is seriously divided and that any attempt to impose the Islamist model would cause strong resistance from both the army and secular forces – namely, those citizens who voted for former Prime Minister Hosni Mubarak Ahmed Shafiq in the second round of presidential elections. Turnout was low, but votes were divided almost equally: Mursi won by only a few percent.

In the short turn, one will need to look at how relations develop between Mursi and the army and at Egypt’s international relations. I do not think that Egypt will withdraw from peace talks with Israel any time soon, although relations may cool. The Muslim Brotherhood and President Mursi cannot afford an agenda that is too radical, since Egypt’s revenues actually come from three main sources: tourism, tariffs for use of the Suez Canal, and American aid, which will continue as long as Egypt remains an element of stability and predictability in the Middle East – which includes maintaining relations with Israel. So I do not think there will be any surprises here.

As for domestic policy, no sudden shifts are expected here either. Mursi will likely gradually replace officials and officers with more loyal ones, but that process will take many years. Today Mursi and his Islamist supporters are in a rather difficult situation. They are now in power and have to take responsibility for two things that bother Egyptians: security and the economic situation. In such a situation it is in the Egyptian government’s interests to defend the rights of Christians and to prevent confessional conflicts, because blame for any such conflict will now be placed on the government.

Christians in Egypt are always in danger: the conflicts that took place between Muslims and Copts under Mubarak and Sadat will likely continue into the future. But I do not think there is any danger of mass repressions against the Copts. Any inter-religious violence would bring the army back to power.

If the country begins to slide into chaos, the army will return, saying: “You wanted democracy – have a look at what came of it. The experiment failed. Thank you, and you are free to go.” They still have the power to do this. The army is an independent (which is not to say “ideal”) player in Egypt. Army officers control much of the economy. One of their primary objectives is to maintain their privileges, their high-ranking position, and their untouchable caste in Egypt.

Even in countries that do not really know democracy (such as Egypt for the past sixty years) concepts such as legitimacy and accountability of power still exist. Having gained political success, the Muslim Brotherhood is going to have to guide a very complex country.

It seems to me that the best option for Egypt would be to follow the Turkish model, in which the military and the moderate Islamist government coexist. On the other hand, Turkey differs considerably from Egypt in a whole variety of ways, from the population’s literacy levels to state and societal institutions. But at the very least I can say that the Turkish model from the end of the 1990s to the early 2000s – when balance was maintained between the army and the Islamists – could serve as an example for Egypt today. There is a relatively high level of democratic freedom in Turkey and it is a stable country with a much clearer idea of itself and a much more responsible political class than in Egypt.

Translated from the Russian