Boredom is one of those self-defining words. For me, the experience of ‘bore-dom’ feels like something boring a hole through my soul, like a hand drill boring a hole through wood. Boredom is a suffering, yet a suffering caused not by something happening, but by nothing happening.

(Just as I am editing this article to publish my 9 year old son is balled up in our livingroom literally crying over how bored he is.)

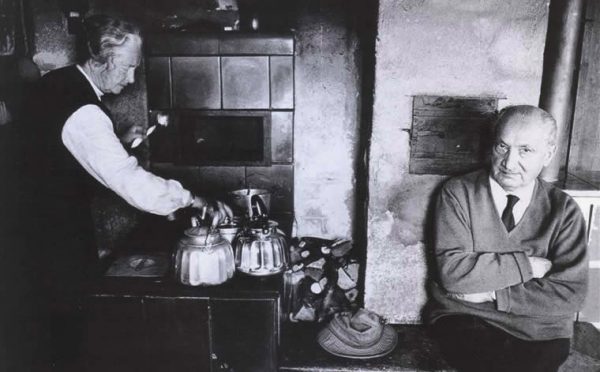

Boredom is an acute encounter of existence stripped of its distractions. And it is this experience with naked existence which accounts for the anxiety it produces, causing one to cling all the more to his chosen distractions. Martin Heidegger wrote, “We should not be at all surprised if the contemporary man in the streets feels disturbed or perhaps sometimes dazed and clutches all the more stubbornly at his idols when confronted with this challenge and with the effort required to approach this mystery.”

Considering the fact that boredom is a universal human experience one would think there would be endless writing on the subject trailing back for centuries. This is not the case. When Heidegger wrote in the early 20th century, he was perhaps the first philosopher to work a thorough investigation of boredom. Spanning roughly 200 pages, Heidegger teased out all the attributes of boredom and discovered that there were at least 3 varieties: (1) becoming bored with something, (2) being bored with something, and (3) profound boredom.

He discussed the final form—profound boredom—in such a way that during my first reading of it I felt that I was having a mini-enlightenment (granted I was simultaneously smoking an amazing cigar so there may have been some cigar buzz crossover).

A blog article is no place to attempt a study worthy of Heidegger’s treatment of profound boredom; with all of the unique terms and layers of thought upon which he builds, it is nearly impossible to lift a few quotes and safely transplant them into an article such as this without completely butchering the whole thing. But not all hope is lost. After reading the text several times and using his thoughts in my own practice, I’ll give a quick example of the feeling produced by profound boredom to which hopefully the reader will easily relate:

If you’ve ever sat alone at the beach, or in the mountains, or the country, or sat gazing at the fully illumined night sky and had that deep sense of your own smallness, of your own seeming triviality in the broad scope of existence, and yet rather than crushing your soul it gave you a sense of calm wonder, a sense of spiritual ordering, then you’ve likely had the experience of profound boredom as Heidegger described it.

In short, what I found so powerful in the notion of profound boredom is that boredom has the power to grant a person “attunement” to oneself and to existence as a whole—or more properly speaking, attunement to Being as a whole—in a truly spiritual manner. Rather than causing torment, boredom, if used properly, can be at once a guide to peace and a guide to the very mystery of being.

If boredom creates a panic response, a depression, or any sort of neurotic avoidance it’s a signal that something is off. As Pascal said, “The sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his room.” If I experience boredom as oppressive—that is, if being in my own company is oppressive—then, clearly, I am not at peace with myself.

By the way, I do not mistake myself for an authority on this. I run from boredom as fast as the next person. The only advantage I have being a psychotherapist is a daily diet of clients dealing with this very thing, which keeps me keenly aware of my own situation. Sometimes just as I turn to run from boredom I am able to catch myself in the act and discover what is lacking. Nearly every time I find that the anxiety felt in the presence of boredom is a perfect measure of my distance from the presence of God. From there it is a simple adjustment of focus.

Perhaps “simple” is too simple a word choice. It’s very likely that such an “adjustment” is the very thing that requires a lifetime of discipline to acquire.

At any rate, perhaps the best use of an article of this size for a topic this dense is to give a few basic steps in accessing and using profound boredom. My thoughts on this is still a work in progress so feel free to let me know in the comments if you have anything to add:

1. Don’t wait for boredom to find you—search it out.

Turn off every device you own, find an empty space, and allow boredom to set in. Experiment with what it feels like to be a human-being rather than a human-doing. This is not meditation per se, but a mere willingness to be undistracted. If you have access to nature, use it. Being in nature is always a shortcut. Turning the tables on boredom might be all it takes to get yourself into an attunement with the immediacy of existence.

2. Once there, allow boredom to reveal its message.

Boredom always comes with a message about yourself and your relationship to being. One way to tap into it is to simply notice what happens to you: Does anxiety increase? Does sadness increase? Is there any anger, frustration, fear? Does your body react to it? (if so where and how?) We moderners rarely encounter naked existence which can make a brush with it feel like a leap into the dark. Let the encounter be what it is for however long it lasts (maybe its an hour, maybe its 20 seconds) and then get up and do something else—return to your distractions.

3. Repeat the above.

Repeat this preferably on a daily basis until you build up an acquaintance with boredom to the point that the negative reactions cease; do it until it becomes a place of rest and not of fret. This is essentially what the Taoist philosophers would describe as creating a void and allowing nature to fill it. Having constant, intentional encounters with the “void” allows growth to happen in ways unmatched by any other means.