It seems remote, the Russian steppe on that July evening of 1015. Tents were being pitched. A prince, Boris, Vladimir’s son, was camping for the night with his retinue of a few hand-picked men. They were particularly conscious that evening of their limited numbers since earlier that same day a whole army had been marching with them. Now it had gone: the army had deserted its prince. The enemy, moreover, was on its way.

When Boris had ridden out earlier in the month to face the nomad enemies of Kiev, it had been Vladimir, the Grand Prince of Kiev, who had sent him. Now he was dead, and the first step toward the settlement of the disputed succession had already been taken in Boris’s absence. His brother Svyatopolk, had been conveniently placed at Vyshgorod, a few miles along the river from Kiev, under his father’s surveillance, having only two years earlier been imprisoned for conspiring with the Prince of Poland, his father-in-law, against Vladimir. He had not hesitated to seize the throne.

Boris, it was felt, was not going to accept this coup d’etat and withdraw. There was certainly no need to. The people of Kiev, it seems, were more in his favor; a fair-sized army was at his disposal, eager to be of service.

The astonishing fact is that Boris refused to fight his brother for the throne. A recent study of these events finds this “absurd” and “inexplicable.” Indeed it seemed so to Boris’s army, for it was at this point that it deserted him.

Boris’s decision was in no way strategic; it made no sense in the eyes of the world. He was resigning his chances as a Grand Prince: more than that, he was putting his life in danger. For “I believe my brother [Svyatopolk] is obsessed by worldly cares,” he says in the Tale of his life, “and thinks of killing me.” It was true enough; Svyatopolk had already despatched men of Vyshgorod with orders to kill him. Yet Boris was well aware of what his course of action ought to be. “If he attempts to kill me” continues the Tale “I shall be a martyr to my Lord, since I shall not resist… For the Apostle says: ‘If any man say, I love God, and hateth his brother, he is a liar’.” (Three accounts of the lives of Boris and Gleb have come down to us: the Tale; the Chronicle account; and the Reading by the monk Saint Nestor. It is disputed which text is the earliest. Quotations used here are from the Tale unless otherwise stated.)

It is all very well for him, we may say. That is the way for a saint to talk in his life, it is natural for him. But the Tale is a welcome corrective to this attitude. It shows us that the decision was by no means easy for Boris, no easier than it would be for us. It shows us Boris in tears, full of regret for the lost pleasures of life, full of sorrow for his own fine body that was soon to be cut down. Concern for the pleasures of life, for his physical self was nothing out of the ordinary.

But Boris did not stop at that: he combated his sorrow by considering the ephemeral nature of the “glory of this world,” of “rich food and swift horses, great possessions and honors innumerable.” After all, his ancestors had all these, “yet for them already these things are now as if they never existed.”

To this reappraisal of what the world has to offer he added contemplation of his own eternal destiny.

Though he lay down to sleep after Vespers, his thoughts gave him little rest. He thought of “how to surrender himself to suffering; how to suffer, and so end the race, so sustain the faith, as to receive the prepared crown from the hands of the Almighty.”

The murderers arrived when it was still dark: but Boris, as they could hear, was already up and at prayer. “O Lord Jesus Christ, who in this form didst come down to us on earth” (he was praying before an icon) “and who of thine own free will didst deign to be nailed upon the cross and endure suffering for our sins: vouchsafe me also to end suffering.”

He had not long to wait. The murderers broke in and he was wounded but they granted him a last few minutes for prayer. From prayer he turned to them in tears. “Brethren, approach and complete your work; and peace be with my brother and with you, brethren.”

He was cut down and carted off, apparently dead. When later he showed signs of life, he was given a final stab in the heart. They took him to Vyshgorod and buried him.

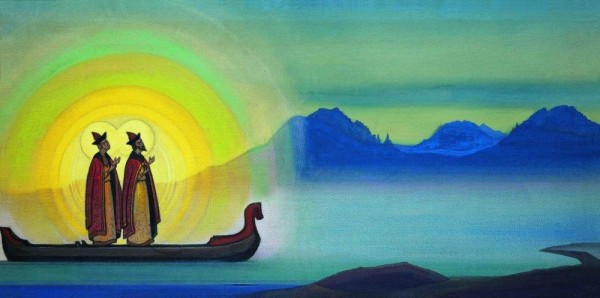

Svyatopolk now turned his attention to Boris’s younger brother, Gleb. A message was sent to him, inviting him to Kiev. Gleb set out for the capital from a distant province where he ruled. Another message reached him en route, warning him of Svyatopolk’s treachery. He was none the less completely unprepared for the murderers when he saw them, coming in their boat to meet his. In his innocence, he had not the slightest suspicion that anything was amiss. The murderers “when they saw him grew morose and rowed toward him: yet he hoped to receive a friendly embrace from them. [But] when [their boat] was level the villains began to jump into his boat, with naked swords in their hands which glittered like the water.”

Boris had prepared for his death and attained a certain calm before he had come face to face with his murderers. Gleb was granted no such opportunity. None the less, in miniature, he passed through the same stages as his brother.

At first, like Boris, he prayed for life. This was the period of the greatest upheaval and the greatest frailty. In his distress he turned to prayer, and it was through prayer that Gleb, like his brother, gained increasing confidence and strength. “I am being slain,” was his prayer, “and I do not know the reason… But this I know: O Lord, my Lord, Thou knowest.” At the end he was able to submit calmly. “Cursed Goriaser ordered his throat to be cut quickly. And Gleb’s cook, Torchin by name, drew his knife and with it slaughtered the blessed one, a meek lamb… And be was brought to the Lord a pure and fragrant sacrifice.” His body was thrown onto the river bank and left to the beasts. (Six years later the body, found uncorrupted and unharmed, was taken to Vyshgorod and buried by the side of Boris.)

I suggested earlier that these events seem remote. Do they not concern us at all then?

There are different ways of looking at the lives of saints. We may deny they ever happened. We may admit they happened yet deny their relevance for us. Or we may accept their relevance and learn from them. What can we learn from the lives of Boris and Gleb?

We see them facing death. Are not we, with them, awaiting death? How do they face it? At first, alone and — like us — afraid. There is no one at hand to help them. They are not immediately willing to submit. There is no cheap victory when it comes. The agony of Gethsemane precedes the submission of Gethsemane.

Yet no sooner have they submitted than they find they are no longer alone in their agony, they are under Christ’s yoke, he is lifting the weight off their shoulders. He is their partner under the yoke; they walk through the valley of the shadow of death, and they fear no evil: His rod and His staff comfort them.

Under this yoke, it is not for them to fight: “I am a soldier of Christ,” in the words of St. Martin of Tours, “I am not allowed to fight.” But Svyatopolk is evil, says the world. Oppose him; you have the force, use it, your cause is just. You will live and rule your people wisely. Even the justice of their cause does not provoke them: was not the most just of causes defended by Peter in Gethsemane, and was he not rebuked? Could not the Son of God have called down more than twelve legions of angels to His defense? Yet He submitted.

Boris and Gleb, in these last moments, link their lives with Christ’s, and, with Thomas the Apostle, they are able to say: “Let us also go with Him, that we may die with Him”

Let us go then, to die, for as Fr. Lev Gillet remarked, “even if there be no prospect of immediate death, we should die in detail for others.”