St. Tikhon’s Orthodox University in Moscow is celebrating its twentieth birthday. Here its rector, Archpriest Vladimir Vorobyov, tells its story – one that shows in microcosm the renewal of church life in Russia after the fall of communism.

Fr. Vladimir Vorobyov

People thirsted for the word of faith

When perestroika began and freedom came, several Moscow priests – Fr. Dmitri Smirnov, Fr. Alexander Shatov (now Bishop Panteleimon [of Smolensk and Vyazma]), Fr. Alexander Saltykov, Fr. Valentin Asmus, and I – began giving short lectures in various parts of Moscow. At first we gathered in movie theatres. As soon as the lectures were announced, the theaters would be jam-packed. People hungrily listened to the lectures and asked questions – it was living, intense interaction.

After a certain amount of time, it was suggested that we offer an annual course of lectures. We agreed to rent the magnificent hall at the Central House of Culture for Railway Workers on Komsomolskaya Square, where we gave weekly lectures for an entire year. We attracted several more priests, including Fr. Gleb Kaleda, who at that time was still hiding his priesthood and would come simply as a professor and PhD.

After a certain amount of time, it was suggested that we offer an annual course of lectures. We agreed to rent the magnificent hall at the Central House of Culture for Railway Workers on Komsomolskaya Square, where we gave weekly lectures for an entire year. We attracted several more priests, including Fr. Gleb Kaleda, who at that time was still hiding his priesthood and would come simply as a professor and PhD.

Elevation of the memorial cross

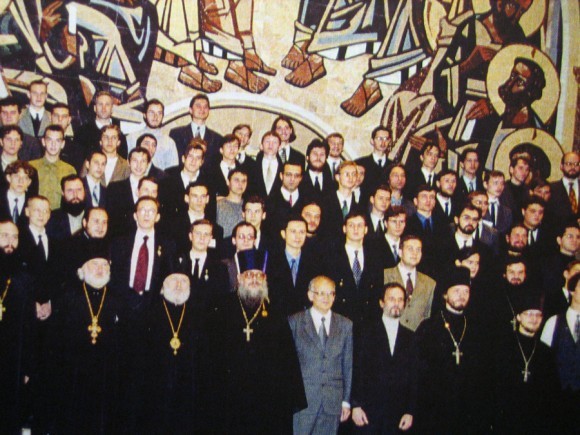

At the origins of St. Tikhon’s. Center: Fr. Vladimir Vorobyov and Fr. Alexander Saltykov

The presentations continued to draw many people: they became famous throughout all of Moscow. Entrance was free. We did this for two years. In the spring, when the lectures were over, people began asking us to start courses – they wanted to receive at least a little theological education.

At this time Orthodox brotherhoods began forming, normally initiated by priests and laypeople. Due to the instability of the political situation, the higher ecclesiastical authorities were in no rush to respond to the new opportunities generously offered by the times. Seeing this indecision, the laity united independently. We, too, founded the Brotherhood of the All-Merciful Savior, which held talks.

The Patriarch decided to create a Union of Orthodox Brotherhoods so that the brotherhood movement would not move away from the Church.

The Union of Orthodox Brotherhoods was organized by activity into fifteen sectors. Everyone was able to choose which sector they wanted to work in. We, of course, chose the education sector. We decided to open catechetical-theological courses and chose Fr. Gleb Kaleda as our rector, to help him legalize his priesthood. Fr. Gleb had been secretly ordained in 1972 by Metropolitan John (Wendland) of Yaroslavl and Rostov who, for reasons of safety, had not put a date on his ordination papers. When Fr. Gleb later took this document to the Patriarchate, they did not accept it because there was no date. We thought that being rector might help Fr. Gleb in this situation.

Fr. Gleb Kaleda became rector of the courses. He very quickly found accommodations. We sat down together, put together a curriculum, and assigned classes. The courses began to operate in February 1991.

Another sector that began active operation was the charitable sector. In those years a great wave of humanitarian aid came to Russia from the West, which then needed to be distributed to various parishes, monasteries, and schools. Fr. John Ekonomtsev suggested to His Holiness, Patriarch Alexy, that two synodal departments be created: one for religious education and catechesis and the other for charitable work.

Another sector that began active operation was the charitable sector. In those years a great wave of humanitarian aid came to Russia from the West, which then needed to be distributed to various parishes, monasteries, and schools. Fr. John Ekonomtsev suggested to His Holiness, Patriarch Alexy, that two synodal departments be created: one for religious education and catechesis and the other for charitable work.

Our courses went well and the new synodal department picked up Fr. Gleb. Then Fr. John asked His Holiness the Patriarch about Fr. Gleb, and the Patriarch received him into the ranks of clergy. Our goal had been achieved.

But in the spring of that year Fr. Gleb, who was already visibly ill, said that it was difficult for him to fulfill all his duties: he was rector of the courses, and he headed the main sector of the synodal department, and was a parish priest with a large flock. He was sorry to leave the courses, but he nonetheless asked that he be replaced as rector. Then I was chosen rector of the courses.

From courses to an institute

It soon became apparent that the courses needed to be turned into an institute. This was by request of the students, for whom two years did not seem like long enough to receive a religious education. The academic council of the courses voted in favor. In March 1992 we were registered as a theological institute, founded by Patriarch Alexy and the Holy Synod.

It soon became apparent that the courses needed to be turned into an institute. This was by request of the students, for whom two years did not seem like long enough to receive a religious education. The academic council of the courses voted in favor. In March 1992 we were registered as a theological institute, founded by Patriarch Alexy and the Holy Synod.

Our presentation as a theological institute took place in the autumn of 1992. A joint agreement was signed by Patriarch Alexy and Viktor Sadovnichiy, rector of Moscow State University. But the Minister of Justice said that a state university cannot found a religious educational institution, even jointly with the Patriarchate.

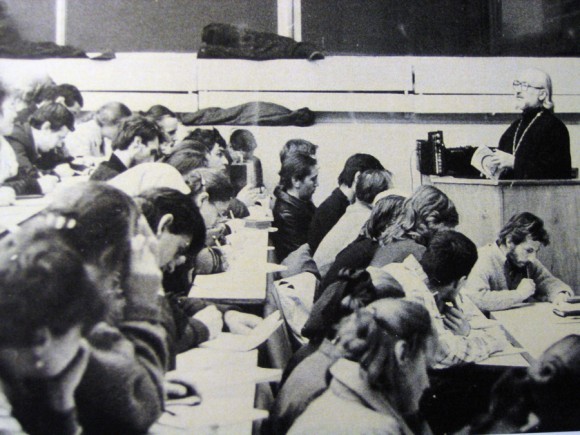

Lecture in the First Humanities Building, Moscow State University

By motion of the academic council, the institute was named after the Holy Patriarch Tikhon. During the first years, Fr. Gleb Kaleda taught a course in scientific apologetics, of which he was very fond. But his strength declined and he gave up teaching. Fr. Gleb died in 1994.

Some of our students spent the night in train stations

The people attending our catechetical courses, which were then moved to the second and third years of the new institute, became our first students. For the first year courses we recruited parishioners of our church (St. Nicholas of Myra in Lycia, Kuznetsk Sloboda) and other Moscow churches. At first there were only evening students, from whose ranks very many good priests later came. We did not have enough teachers and we had no money. It would happen that a capable student would study in the third year while teaching in the first and second years. The future priests Oleg Davydenkov and Alexander Prokopchuk were student teachers. Teachers had to work for little or no pay.

There were instances when students coming from afar, who had not been able to find housing, spent the night in train stations and then came to lectures in the morning. We opened a charity canteen to help support them. A commission organized by the Department for External Church Relations was able to receive a grant from the World Council of Churches. With that grant money we put together a canteen out of several trailers behind the St. Nicholas Church in Kuznetsk. We obtained foodstuffs from humanitarian aid: we fed students with instant mashed potatoes from America or with rice without oil. The students were grateful for even this.

Fr. John Meyendorff’s final lectures

Once, in the spring of 1992, during the reading of the canon at the Sunday vigil, a caretaker came to the altar and said: “They’re calling you to the phone – there’s some priest named John from America.” (This was before the days of cell phones.) I understood immediately who this Fr. John from America was and ran to the caretaker’s lodge. I picked up the receiver and heard the voice of Fr. John Meyendorff coming over the phone: “Fr. Vladimir, I’m in Russia! How can I be of service?” Here was yet another miracle! Fr. John had long been barred from Russia. And then he suddenly arrives when we were organizing our first conference, memorial readings for Archpriest Vsevolod Shpiller, and even offers his help! Of course, I asked him to take part in the conference. He came and gave several talks.

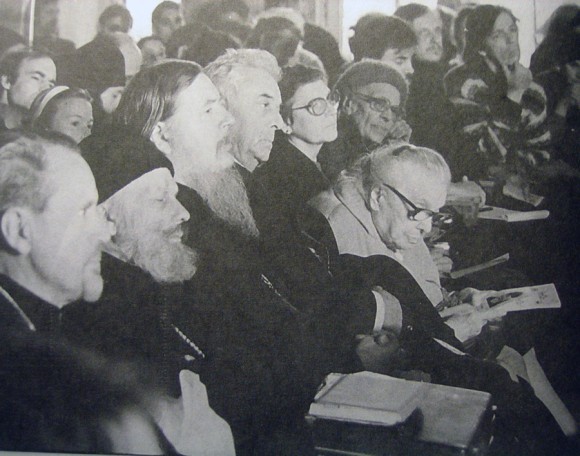

Fr. John Meyendorff, Fr. Gleb Kaleda, Fr. Dmitri Smirnov

The lectures took place in the Church of the Tsarevich Dmitri at City Hospital No. 1 – we had nowhere else. We set up chairs right in the church. Fr. John came and presented his lectures, talked with us, and responded to questions. This was such precious fellowship! Fr. John said that he would like to leave his position as dean of St. Vladimir’s Seminary in New York, move to Russia, and lecture at the Moscow Theological Academy and our institute, which had just opened, and translate his books into Russian so they would become available here.

Our fellowship with Fr. John Meyendorff was so lovely, warm, and amazing that it is difficult to put it into words! On his last day in Moscow we got together at my home, some young priests came, and we had an unforgettable discussion with Fr. John. Everything was somehow especially filled with grace… But then he returned to America and two months later suddenly died of cancer. It turned out that the lectures he gave here were the last of his life…

Thanks to the fact that Fr. John had shown us so much attention and interest, Patriarch Alexy also visited us and spoke here, so the institute received a certain recognition in the eyes of church people. The future Fr. Cyprian (Yashchenko), who was then working in the Department for Religious Education and Catechesis, organized the Christmas Educational Readings on the model of our Shpiller memorial readings.

Thanks to the fact that Fr. John had shown us so much attention and interest, Patriarch Alexy also visited us and spoke here, so the institute received a certain recognition in the eyes of church people. The future Fr. Cyprian (Yashchenko), who was then working in the Department for Religious Education and Catechesis, organized the Christmas Educational Readings on the model of our Shpiller memorial readings.

Christmas Educational Readings

At first the Patriarch’s blessing was received in absentia. Later I went to His Holiness the Patriarch when we needed to re-register our charter in connection with the name-change. I remember our warm conversation with His Holiness the Patriarch, who asked me with a smile: “What, do you really want to create competing theological schools?” I replied that healthy competition is useful and will also help the development of the theological schools.

He agreed with this and signed our charter.

Competition is a good thing when it is done without jealousy. There should also be brotherly cooperation. When you see a friend achieve success in something and you decide to try to keep pace with him, then everything comes out well.

Competition is a good thing when it is done without jealousy. There should also be brotherly cooperation. When you see a friend achieve success in something and you decide to try to keep pace with him, then everything comes out well.

The Moscow theological schools looked at us, and we looked at them. We decided to organize theological education on the university model, while the theological schools had a traditional education of the closed type. Closed education has its own strengths and weaknesses, as does open education.

The Moscow theological schools looked at us, and we looked at them. We decided to organize theological education on the university model, while the theological schools had a traditional education of the closed type. Closed education has its own strengths and weaknesses, as does open education.

Twenty years

I think that the existence of our institute has helped the reform of the theological schools.

The first religious standard for Theological Studies was worked out at the St. Tikhon’s Institute (this was before it had university status). Later this standard managed to gain state approval. Without this standard, the licensing of theological schools and the law on their accreditation, which was recently passed, would never have been possible. The development and approval of a state-policonfessional standard in Theological Studies is an important milestone in the development of theological education in Russia – in the development, moreover, of education that is specifically confessional, not atheistic or agnostic. Our university, I think, made a considerable contribution to overturning Lenin’s “Decree of Separation of Church and State and of School and Church.”

The first religious standard for Theological Studies was worked out at the St. Tikhon’s Institute (this was before it had university status). Later this standard managed to gain state approval. Without this standard, the licensing of theological schools and the law on their accreditation, which was recently passed, would never have been possible. The development and approval of a state-policonfessional standard in Theological Studies is an important milestone in the development of theological education in Russia – in the development, moreover, of education that is specifically confessional, not atheistic or agnostic. Our university, I think, made a considerable contribution to overturning Lenin’s “Decree of Separation of Church and State and of School and Church.”

Russian legislation is still not free from the influence of Soviet law. According to the law on freedom of conscience, there is secular education and there is religious education. Religious education, as defined by the law, has as its goal the training of clergy – these are the theological schools [i.e., seminaries]. All other education is secular. To this day, secular education in our country, in the vast majority of schools, still corresponds with a standard (or, previously, with the state educational curriculum) that is based on an atheistic worldview.

Russian legislation is still not free from the influence of Soviet law. According to the law on freedom of conscience, there is secular education and there is religious education. Religious education, as defined by the law, has as its goal the training of clergy – these are the theological schools [i.e., seminaries]. All other education is secular. To this day, secular education in our country, in the vast majority of schools, still corresponds with a standard (or, previously, with the state educational curriculum) that is based on an atheistic worldview.

The law is silent on this point, but this is the case de facto. When we told the Ministry of Education that the standard for Theological Studies, of which the ministry then approved and which had been written in the context of scientific atheism, did not suite us whatsoever since it was a parody of theology, they told us: “Then write a different standard!” We replied: “You do understand that a standard of Theological Studies cannot be atheistic, but can only be confessional?” They replied that there are many confessions in the country and suggested that we create one standard for all religions. We replied, naturally, that this is not possible – since it is impossible to combine Christian theology with, say, Islamic theology. They said: “What, do you want to make many different standards? So that everyone would have their own standards: Catholics, Muslims, and Protestants? That’s impossible!” Then we offered to make a single policonfessional standard arranged like a “bundle” of standards sharing a common foundation: modules of humanities, economics, social sciences, and natural sciences. And each religion can then write its own confessional modules.

The law is silent on this point, but this is the case de facto. When we told the Ministry of Education that the standard for Theological Studies, of which the ministry then approved and which had been written in the context of scientific atheism, did not suite us whatsoever since it was a parody of theology, they told us: “Then write a different standard!” We replied: “You do understand that a standard of Theological Studies cannot be atheistic, but can only be confessional?” They replied that there are many confessions in the country and suggested that we create one standard for all religions. We replied, naturally, that this is not possible – since it is impossible to combine Christian theology with, say, Islamic theology. They said: “What, do you want to make many different standards? So that everyone would have their own standards: Catholics, Muslims, and Protestants? That’s impossible!” Then we offered to make a single policonfessional standard arranged like a “bundle” of standards sharing a common foundation: modules of humanities, economics, social sciences, and natural sciences. And each religion can then write its own confessional modules.

This was done, but the ministry was in no hurry to approve the new standard, saying that according to the constitution our education is secular and that this standard supposedly violates the constitution. It took several years to demonstrate that the teaching of theology, and of religion-based education in general, can also by secular – that “secular” does not necessarily mean “atheistic.” This took much time and effort, but the work was crowned with success.

This was done, but the ministry was in no hurry to approve the new standard, saying that according to the constitution our education is secular and that this standard supposedly violates the constitution. It took several years to demonstrate that the teaching of theology, and of religion-based education in general, can also by secular – that “secular” does not necessarily mean “atheistic.” This took much time and effort, but the work was crowned with success.

As a result of this victory, religious education has begun to develop very rapidly. Today there are already about fifty theological faculties in Russia, with more than half of them in state universities. The vast majority of them are Orthodox, but there are also Islamic and Jewish faculties.

This standard was the first legitimate act put into law by cooperation of Church and state. There had been such cooperation in other spheres, but without legal grounding. It is written in the standard that teachers of doctrinal subjects should by chosen by recommendation of the Church. That means that from now on our schools are no longer separate from the Church, since religious education without the Church is impossible.

This standard was the first legitimate act put into law by cooperation of Church and state. There had been such cooperation in other spheres, but without legal grounding. It is written in the standard that teachers of doctrinal subjects should by chosen by recommendation of the Church. That means that from now on our schools are no longer separate from the Church, since religious education without the Church is impossible.

Many other new initiatives have been implemented over these years, but if we were to speak of them in detail our conversation would go on for quite some time.

Transcribed by Alexander Filippov. Photographs by Julia Makoveitchuk, Mikhail Moiseev, and from the archives of St. Tikhon’s University.