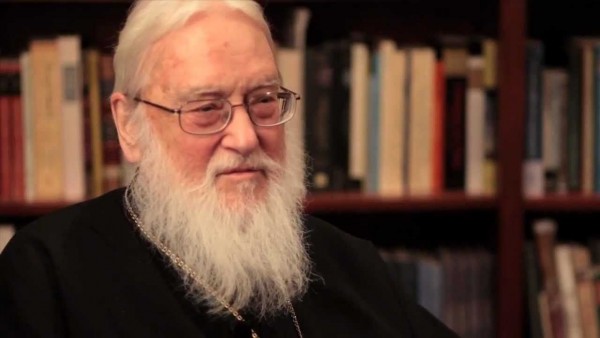

David Frost: Ladies and gentlemen, I really am not going to attempt, for the umpteenth time to introduce Metropolitan Kalistos Ware. But I would like to thank him for making a trip, which I know he does not enjoy, from Oxford to Cambridge; what I would consider a holy and monastic hour coming way over here and going back.

I wake up at night wondering what we are going to do when the times comes, he decides he must stop traveling and teaching to the extent he does. But thank God my lack of faith is once again defeated. He seems to be able to go on indefinitely to this kind of service for us, and it is wonderful. So without more ado, I will introduce him and his topic, which is the $50,000 question as to What is Theology?

Met. Kalistos Ware: Thank you very much, David. One of the great tragedies of my life; one of the larger tragedies has been that in the year 1967 the railway line between Oxford and Cambridge has been closed and just at the time when I would begin to need to use it. And for a long time I used to travel over here by bus, which I found infinitely tedious because I can’t read on a bus. I don’t feel well.

So now I go through London. And train journeys are always enjoyable, but this train journey is interrupted, and I have to go from one terminus to another. This morning however, it was very enjoyable. As I set out from Oxford, the sky was just beginning to light up – a pale blue. And then, between Oxford and Reading, the sky turned red. And by the time we entered London, the sun had just risen. All of that was enjoyable as I looked out across the fields covered with frost; white in color. So I have nothing to regret.

Now when I am working at my desk, I have always two books within easy reach. The first is the Holy Bible. The second is The Concise Oxford Dictionary, which I usually have in two editions – the fourth and the sixth edition. So I looked to these volumes for help in answer to the question “What is theology?” I got no help at all from the Bible, because the word theology never occurs in Holy Scripture. It is not a Biblical term.

However, The Concise Oxford Dictionary was more helpful. The fourth edition defines theology curtly as, “science of religion.” The sixth edition is more expansive. It says, “study of all system of religion; rational analysis of a religious faith.” I wasn’t very satisfied with these two rather dry definitions.

And so I turned to a contemporary Greek theologian and religious philosopher, Christos Yannaras. He provides a rather more exciting definition of theology. He says:

In the Orthodox Church and Tradition, Theology has a very different meaning from the one we give it today. It is a gift from God, a fruit of the interior purity of the Christian’s spiritual life. Theology is identified with the vision of God; with the immediate vision of the personal God; with the personal experience of the Transfiguration of creation by uncreated grace. In this way, Theology is not a theory of the world, a metaphysical system, but an expression of the formulation of the Church’s experience; not an intellectual discipline, but an experiential participation; a communion.

So let us contrast these two definitions. The Concise Oxford Dictionaryuses as its keywords: science, system, and rational analysis. On the other hand, Yannaras has as his key terms: gift, grace, personal experience, participation, communion, interior purity, transfiguration, and vision of God. These are two very different approaches.

In the first case, if we follow The Concise Oxford Dictionary, we will see theology as an academic discipline; something taught in universities; something examined; something which will award people first, second, and third class degrees; something taught in the lecture hall of a university faculty; scholastic, if we would like to use that word.

Yannaras disputes this approach to theology, which he calls, “the approach of academic scientism.” And he wishes to see an essential link between theology and prayer; between doctrine and the spiritual life. And he sees theology not as a matter of detached study, but as involving personal experience.

Perhaps, there is truth in both approaches. Perhaps, we should combine them. God has given us a reasoning brain. Muddled thinking is not one of the gifts of the Holy Spirit, so we should be systematic and rational in our work. We should try to express our ideas with the utmost clarity. I think it was Wittgenstein who said, “Everything can be said at all can be said clearly.”

On the other hand, surely Yannaras is right. Theology is not a science exactly on a level with say geology or zoology. I will come back to that later. Theology involves a personal involvement, such as you might not need in other disciplines. So yes, systematic rational analysis, but something much more than that – personal experience.

Developing Yannaras’ approach, let me call to mind a famous aphorism by the Desert Father Evagrius of Pontus or Evagrius Ponticus he might be called. But Greeks smile when I refer to him as so because Ponticus means mouse. So what has Evagrius the Mouse to say? “If you are a theologian, you will pray truly. And if you pray truly, you are a theologian.” That is a very different definition from The Concise Oxford Dictionary.

Now in this connection, St. Gregory Palamas of the 14th Century distinguishes three kinds of theologians. First he says, there are the saints. They are those who possess personal experience; who have themselves beheld the divine light, and these are the true theologians. Secondly, there are those who lack such personal experience but who trust the saints and learn from them. And they too may be good theologians, albeit on a lower level. Thirdly, there are those who lack personal experience and who do not trust the saints, and they are bad theologians.

I find this threefold distinction reassuring. But while I make no claim to be in the first category of theologians, I hope that by the Divine Mercy, I may find a place in the second category among those who trust the saints. Now, let’s think a little more about what Evagrius and Palamas are asserting here. Let me quote a few other statements from modern Orthodox theologians, which develop Yannaras’ approach.

Here for example is what is said by another Greek theologian, Constantine Scouteris who died recently. And he’s describing what it is to be a theologian. “The whole person, living out the mystery of the new creation – educated, that is to say, ‘through healthy dogmas’ and ‘purified’ – becomes an unceasing hymn and continual praise of God.”

So there you see, theology involves living out the mystery of the new creation; being purified; becoming a hymn in praise of God. Theology is not just something that we do, but on this approach, it’s something that we are. You may recall the words said shortly before his death by the composer Vaughn Williams. He was asked what he thought it would be like in Heaven. And he replied, “Music. Music. Only in Heaven we shan’t write and perform music, we are ourselves will be the music.” Well, you could apply that to theology.

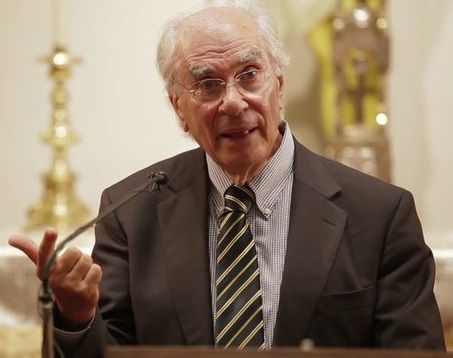

Here is testimony of someone I shall have a lot to say about today, Archpriest George Florovsky who died in 1979. I had the pleasure of meeting him on a number of occasions. He spoke with a very strong foreign accent though his knowledge of English was extensive and accurate. He once surprised an Anglican parish audience by pronouncing the worth faith as if it was face. “Look at my face,” he said. “It is a very beautiful face. It is a profound and extraordinary face. It is a very ancient face.”

The last time I went to see him it was just after Easter and his matushka, to whom he was very devoted, sat us down at the table to eat, according to the Russian Orthodox practice, Kulich and Paskha. And at the table, there was a plate and around the plate on the left were two teaspoons and on the right two teaspoons and at the top of the plate three other teaspoons. And I was given a cup of tea, but I wondered how to use all seven of these teaspoons. I could see my way to using two of them, but what about the other five? I never found the solution to that.

Anyway, here is Fr. George Florovsky. “One cannot separate spirituality and theology. Theology can never be separated from the life of prayer and from the exercise of virtue.” So it is a question of how you pray and how you live. And he goes on to quote St. John Climacus from the 7th Century. “The climax of purity is the beginning of theology.”

Another witness that I’d like to quote in this connection, along with Florovsky perhaps the greatest theologian in the Russian emigration during the 20th Century, is Vladimir Lossky who died in 1958. He argues powerfully that all theology is essentially mystical.

Far from being mutually opposed, theology and mysticism support and complete each other. One is impossible without the other. In the mystical experience is a personal working out of the common faith. Theology is an expression for the profit of all of that which can be experienced by everyone.

He goes on to point out that the three writers to whom par excellence the Orthodox Church has applied the title Theologian. The first is St. John the Divine or St. John the Evangelist, the most mystical evangelist he says. The second is St. Gregory of Nazianzus, a 4th Century writer of contemplative poetry as Lossky describes him. Finally is St. Symeon the New Theologian, an 11th Century singer of union with God.

All theology then is mystical, and we might add that all theology is liturgical. If there’s an essential connection between theology and prayer, then that does not only mean inner prayer, it means, and perhaps much more importantly, the public prayer of the Church – the Liturgy and the Divine Office. So that is a general approach to theology and a general answer to the question, “What is theology?”

It is linked to prayer, liturgical, and mystical. But also, it involves the rigorous use of our reasoning brain; of our power of articulate speech. Mystical does not mean irrational. Developing this approach to: “What is theology,” I’d like to think in terms of four words. The first is charisma. The second is mysterion. The third is catharsis. And the fourth key word is hesychia.

So my four key words are charisma meaning gift or grace, mysterion meaning mystery, catharsis meaning purification, and heyschia meaning silence or stillness of the heart. So let’s think about those four characteristics a little bit more. Theology is a gift, a free and underserved gift, and a gift of grace. Theology, in other words, signifies not our human inquiry into the being and life of God, but rather God’s disclosure of Himself or His self-revelation. Theology is not so much us searching out and examining God, but rather God searching us and examining us.

In secular scholarship, the human person knows. But in theology, the human person is known by God. So theology rests upon a divine, rather than upon a human initiative. In theological research, God is never the passive object to our knowledge but always the active subject. Another way of putting this would be to say that theology depends upon revelation. And that’s something I will be developing in my second talk this morning.

We might make the same point by saying that theology is wisdom not just scholarly inquiries and academic learning, but wisdom. The True Wisdom however is always Christ Himself, living hypostatically; the Power of God; the Wisdom of God as Paul says in 1 Corinthians 1:24. Christ Himself is theology. He is the Theologian. We are theologians only by virtue of the charisma that we receive from Him. A genuine theologian is always theodidaktos or taught by God.

So at the very least, this must mean that theology presupposes personal faith. Human reason is indeed essential if we are to theologize coherently. But our human reason can be effectively exercised only within the context of faith. And there I think we have the difference between theology as a science and zoology as a science. You can study zoology without having any particular personal faith, but I don’t think you can do that in the case of theology.

Here I might recall the Western writer, Anselm of Canterbury who was not perhaps very sound on the Filioque, but he had some good things to say. And one of his key remarks was Credo ut intelligam or I believe in order to understand. So what comes first is belief and then out of your belief comes understanding. You don’t first understand and then believe, but for Anselm it comes the other way around.

He spoke of Fides quaerens intellectum or faith seeking understanding, not the other way around. So if you are to theologize in the way that Yannaras and Florovsky and Lossky would have us do, we do need to work from faith. And that I think marks the difference between faculty of theology in the university and the faculty of religious studies.

A faculty of religious studies means you are just gathering facts about what Christians and other faiths believe, but you are doing it in a purely detached way. A faculty of theology implies rather more than that. In Oxford now, they are proposing to stop calling themselves a faculty of theology and to say they are a faculty of religious studies. I am a little uneasy about this change, but that’s the way things are going in our secular university.

Now my second key quality is mysterion or mystery. This is a phrase the Greek Fathers often used – the mystery of theology. But if we are to appreciate what it means to call theology a mystery, we need to recall the true religious meaning of this word – mystery. In a religious context, a mystery is not just a riddle, an enigma, or an unsolved problem. A mystery is something revealed to our understanding.

So mystery is bound up with the idea of revelation but something that is never exhaustively revealed, because it reaches out into the infinity of God. Something is revealed, or something remains hidden. This is what mystery implies in the New Testament. Though the New Testament doesn’t contain the word theology, it often uses the word mystery, and I urge you to get hold of a concordance of the New Testament and look up the different uses of the word mystery, particularly in the Pauline Epistles of Colossians and Ephesians.

You will find if you do this that mystery is bound up with the Incarnation of Christ. It’s the birth of Christ on Earth which is the mystery hidden from before all ages, which the angels did not know about. But in the birth of Christ, the mystery is revealed, and yet we never fully understand what is meant by the Incarnation. So mystery implies both revelation and hiddenness.

So theology is a mystery in this religious sense, because it transcends our mind; because it is dealing with things that cannot be fully understood. We might recall T.S. Eliot’s phrase, “A raid on the inarticulate.” I see David smiling. You like a few literary quotations, I think. “A raid on the inarticulate,” that could be a good description of theology.

John Meyendorff, another important theologian from the Russian emigration, says that theology is the expression of the inexpressible. St. Basil the Great remarks, “Every theological statement falls short of the understanding of the speaker. Our understanding is weak, and our tongue is even more defective.” So that’s two levels there. First, we do not even understand the things about which theology is concerned. But secondly, even that which we do understand, we cannot adequately express in words.

According to Basil and the other Cappadocians, once theology forgets the inevitable limits of human understanding; once it replaces the ineffable Word of God with our limited human logic, it ceases to betheologia and sinks to the level of technologia or technology, which was a pejorative term in the Cappadocians. So we must try to be theologians, not technologians.

And we might recall Paul, in 1 Corinthians 13:2, we see through a glass doctored. Theology has to be expressed, using Paul’s words, in a riddling and enigmatic way. And this means that in theology we are often stretching human language beyond its proper limits. Our language is adapted to speaking about the things of this world, but in theology we are reaching out into the age to come. And to do that, we have to speak in a riddling, enigmatic way.

Indeed often in theology, we have to seem to be contradicting ourselves. There’s a place in theology for antinome or affirming two statements which seemingly contradict one another. Yet on a level higher than our human logic, there may be a reconciliation. St. Gregory Palamas says that the mark of the true theologian is to say sometimes one thing and sometimes another when both are true. And Cardinal Newman made the same point when he said, “Theology is saying and unsaying to a positive effect.” So we have to perhaps contradict ourselves, and yet we don’t just thereby talk nonsense, but we actual convey beyond the contradiction, a positive message.

Another way of making this same point is to say that in theology we use two approaches – a cataphatic and apophatic. Those are actually two ways of saying that theology is both positive and negative. So in theology, we make a positive statement, and then we make a negative statement. We say, God is just, but then we have to say that He is not just as we understand it. We say God exists, but then we say that He does not exist in the same way that created things exist. He is not just one existent object among others; He is unique.

So this is what is implied by saying and unsaying. You make an affirmation, but then you seemingly withdraw it by negating it. And yet the negation is on a higher level than the affirmation and takes you more deeply into the truth. To illustrate the meaning of these two approaches to theology, apophatic and cataphatic, let me quote from another book, which I keep close beside me when I am working called Signs of the Times.

Some years ago the Times Newspaper in London ran a competition in which people were invited to send in puzzling and unexpected signposts and notices, which they had seen in different places. For example, one such notice came from Wales in a parking lot. It said, “Waiting is limited to 60 minutes in each hour.” You can work out what that means yourself.

And elsewhere from a marketplace was a notice saying “Cattle and cars turn right. Pigs straight on.” And then where it said, “Turn right,” there was a large arrow pointing left. And as the Times rightly commented, it seemed unnecessarily cruel to cattle who have taken the trouble to read to try and confuse their sense of direction.

Another one from Africa is “Elephants have right of way.” Well, here are two notices from this admirable collection. The first illustrating cataphatic approach – a careful sign conveying all eventualities. You have a railway line and a pole with a box which evidently contains a bell. And beside the box, there’s a notice saying, “Danger! Stop, look, and listen! When the bell is ringing, do not cross the line. If the bell is not ringing, still stop, look, and listen in case the bell is not working.” So there you have all possibilities accounted for, a very cataphatic notice.

But here is an apophatic notice from Australia. There is a sign post saying, “This road does not lead either to Cairns or Townsville.” It doesn’t tell you where it leads. But on the other hand, if you know the geography of the country, this negative sign might convey to you a positive message. And that is also true of apophatic or negative theology.

I don’t think apophatic and cataphatic are alternatives. All theology needs to use both approaches. But the apophatic, rightly used, takes us further into the mystery than does the cataphatic. The apophatic can act as a kind of trampoline, by which we can bounce off into the mystery of God.

Then, the third quality in theology is catharsis or purification. Although theology remains a gift of God’s grace, this free gift requires, on our human side, our active cooperation. We have to play our part. We are not just passive. In order to be receptive, we have to purify and prepare ourselves for the vision of the truth. And I might quote here 1 Corinthians 3:9. “We are fellow workers with God.”

So in theology there is cooperation or synergia. Theology istheanthropic involving both God and man; both the divine and human person. Our human cooperation is required in theology as well as our conversion, our obedience, our opening of our hearts to God’s love. Theology, in this way, is a matter of lived experience. It’s a way of life. There is no true theology without a personal commitment to holiness.

The real theologians are the saints. And this, as I’ve already said, shows how theology involves much more than the systematic use of our reasoned brain. This is why theology is not just a science. Then, the fourth quality of theology as understood by the Fathers is hesychia, inner stillness, or silence of the heart. “Be still, and know that I am God.” –Psalm 45.

Theology as the knowledge of God is not merely talking about Him but also listening to God. So we cannot be genuine theologians if we have not learned to be silent and to listen. I remember a story told by a friend of mine who attended an interfaith conference in California. And first of all, the Jewish representative got up and spoke. And he just told a few jokes, and then he sat down in the usual rabbinic way.

And then the Zen Buddhist representative got up, and he uttered a few riddling poems and sat down. Then, he said the Christians started. And they talked and talked, and they made distinctions about “Yes, you say this, but I say this.” They made comparisons. They analyzed the concepts, and he thought, “How clever they are. How do they know so much about God?” And then he thought, “If they know so much about God, why can’t they just keep quiet?”

Well, that’s a little unfair to people like me who spent their lives teaching theology. You might be a little disappointed if I came here and said that my three thoughts would be given entirely in silence. But let us remember, there is a place for silence; a waiting on God; for listening to Him.

Those then are the marks of theology that I would want to distinguish. I’d be interested if you, in your term, will have some other qualities you’d want to mention. But perhaps I’ll quickly mention three other points. Theology for me presupposes first of all freedom, exploration, and creativity. Now we have, unfortunately in our Orthodox Church today, a number of zealot groups who are extremely negative about anyone who disagrees with them and understands Orthodoxy in a slightly different way.

They reduce Orthodoxy, all too often, to a series of negations. And surely, Orthodoxy can’t be that. And these people, often very sincere people, act unfortunately as a blackmail party. They frighten others into saying things that might be thought controversial. They quench the spirit of freedom and exploration. So I would appeal then to the importance of freedom in theological inquiry. And let us not be too quick to condemn those who have a slightly different approach from our own.

A second quality which we need in theology is fear of God. We should embark on this task not light-mindedly but with a sense of awe. Let us recall what is said in the Liturgy just before the anaphora, the Deacon says, “Let us stand aright. Let us stand with fear.” And later on the priest, inviting people to come forward for Communion, says, “With fear of God; with faith and love, draw near.” So we need fear of God, not blind terror but a sense of awe about what we are embarking on.

And the third thing in theology, I think we need is joyful wonder. As theologians, we need not to be dreary. There’s a place in theology for jokes. Indeed, I would think jokes have a real eschatological significance. Part of the element of a good joke is that you are taken by surprise when you come to the punch line. That’s why, when telling a joke, you need to have a good sense of timing.

You mustn’t anticipate the point. You mustn’t keep breaking up and saying, “This is frightfully funny.” That will simply alienate your audience and spoil the effect when you come to the point. You need to take them by surprise. And this element of surprise in a joke means that you’re startled, and this helps you to reach out to a new understanding. And I think precisely, jokes in theology can fulfill this kind of thing.

Now I do remember, after I’ve been lecturing in the university for 35 years, they introduced the system of the students filling in an assessment form. And these were duly passed on to the lecturer. And one of the people who had been in my audience said as a comment, “He tells too many jokes.” So he didn’t think jokes had a place in theology, but I think jokes do. And more generally, there should be the element of joy in theology. And there should be the element of wonder. Thank you.