Source: Saint Herman Orthodox Seminary

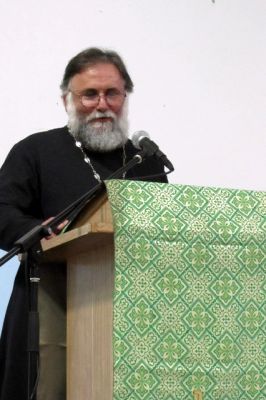

Fr. Robert Arida’s Commencement Address at Saint Herman Theological Seminary, Kodiak, Alaska

Fr. Robert Arida’s Commencement Address at Saint Herman Theological Seminary, Kodiak, Alaska

The theme of my address is theological education. It comes as no secret that for many outside of the seminary community, theological education is nothing more than a costly luxury, which the Church–particularly the Church in Alaska–can do without. For some, in and outside of Alaska, St. Herman’s Seminary has deviated from its intended path by striving to provide a quality theological education to its students, who will return to homes and villages to serve the faithful and to catechize those seeking to enter the new life in Christ.

Theological education is not a luxury, nor is it something the Seminary should abandon for some other curriculum that would deprive this diocese of educating and training leaders who will, in time, give their lives to the building up the local Church in Alaska.

Theological education is a necessity that originates in the parish and is further developed and honed through the seminary. My desire today is to speak about three aspects of theology: Theology and Life, Theology and Mission and Theology and Pastoral Care.

Theology and Life

Theological education is bound to life. It is necessary for life. It provides the means by which the relationship between God and humanity can be best articulated. Theological education, because it is nurtured and sustained by the Holy Spirit, is life giving and life forming. For this reason, it cannot be confined solely to the classroom. Here we can benefit from the wisdom of the venerable Father Georges Florovsky who, in an article on ecclesiology, stressed over fifty years ago that any discussion about the Church needed to move from the classroom and return back to the temple. We can use this advice as we discuss theological education and its spiritual and intellectual components. For it is in the temple or, more specifically, it is in the context of our liturgical worship that theology is best expressed and manifested as the celebration of new and eternal life. When theological education becomes separated from the temple and, therefore, from the life of the local Church, it becomes an artifact that has the elusive past as its only point of reference.

Theology is life and not archaeology. For us, the study of antiquity is but a starting point for discerning the interaction between God and humanity that leads to this very moment and continues into the future. In my experience as an instructor at this seminary and as a parish priest, one of the most dangerous reductions of a theological education that I have encountered has been its divorce from life. How easy it is to turn Orthodox theology into an academic discipline as an academic career without spiritual moorings. While our academies and seminaries must demand academic excellence, the curriculum each may offer must be based on the spiritual life. There is the need to instill in the professors and students the fundamental idea that the study of scripture, history, liturgy, patristics and dogmatics cannot be separated from seeking after the “kingdom of heaven and its righteousness.” Academic excellence cannot be allowed to stand apart from acquiring the Holy Spirit. Understanding theology or theological education as something parallel to the life in Christ inevitably generates its own dynamism that, in turn, manipulates the words proper to God into becoming a false theology. This false theology, resulting from an alien spirituality, abandons its evangelical thrust by replacing human salvation and transfiguration with the illusions of social and political utopias.

The spiritual and intellectual formation of the Orthodox theologian is grounded in the ascetical discipline of the Church. Asceticism seeks to counter a self-centered and self-serving life with one that seeks to love and serve Christ and neighbor. The ascetic ordeal rooted in repentance, prayer, fasting and the reordering of the passions is best summed up by Saint John the Baptist: Christ “must increase, but I must decrease” (Jn. 3:30). These words capture so well the life of the ascetic theologian. They express a way of life that ultimately allows the mind and heart to participate in the creative activity of the Holy Spirit. The outcome of this creativity is a living and true theology that utilizes and responds to the new questions and challenges of the 21st century. Science, technology, globalization, local, national and world politics, the suffering and termination of the unprotected and the innocent, human sexuality and the abuse of the environment are beckoning the Orthodox Church and, therefore, Orthodox theology to enter the fray of modernity.

Theology and Mission

Theology is evangelical. Unfortunately, the missionary responsibility of our Church continues to be undermined by ethnic chauvinism. Until it becomes clear to the Orthodox themselves that every local parish is, by definition, a missionary community and responsible for offering the Gospel to all people, theology will remain separated from life. Every parish must strive to be a center of spiritual and intellectual formation.

Because theology seeks to proclaim the Gospel in time and space, it has by its very nature a missionary and evangelical quality. This means that Orthodox theology cannot be the possession of a particular people. It is universal in scope, offering the saving and transforming power of Christ’s gospel to all nations. Our history teaches us that as the Church sojourned in time and space, it used the culture of empires and nations to articulate a living theology. This is certainly the method employed by the Church Fathers. Knowing the language, art, philosophy, literature, science and politics of their time, they were able to convey the gospel to people of varying intellectual and social backgrounds. They were able to proclaim Christ who is the “same yesterday, today and forever” (Heb. 13:8), using the cultural tools that were at their disposal.

Today Orthodox schools of higher learning, especially our academies and seminaries, need to promote and develop the patristic method of using culture for the proclamation of the Gospel. Because they knew their culture well, the Fathers were able to interact with its prevailing ethos. They were able to draw the knowledge of their surroundings into a vibrant ascetical spirituality that enabled them to communicate the Gospel freely and openly.

A theology separated from the culture is ultimately a theology separated from the people. To respond to the culture, especially the challenges posed by the rapid development of science and technology, theology is compelled to creatively interact with its environment so as not to fall into a cultural vacuum. The voice of the Gospel and, therefore, the voice of Orthodox theology will be heard only when the theologian truly knows his audience.

While the missionary thrust of theology is directed toward the world, there is the ongoing need to educate the faithful. Sermons, Bible studies, church school curricula and publications are to raise the level of awareness–need to open the minds and hearts of all the faithful. Theological education has the task of instilling in those who would preach and teach the desire to challenge and elevate the minds and hearts of the faithful, regardless of social and educational backgrounds. Too often theology among the Orthodox is relegated to the ivory tower while what is offered the faithful is of the lowest common denominator. Here we need to remember that Holy Scripture and the subsequent writings of the Fathers were written for the education of the faithful. The high theological caliber of St. John’s Gospel, Saint Paul’s Letter to the Romans, and the treatise On the Incarnation by St. Athanasius were and are for the building up of the local Church and not solely for the scientific analysis of academicians.

St. Philaret Drozdov of Moscow reminded his flock that every Christian had the duty to learn. Those who preach, teach and write theology are challenged to stimulate all the baptized to know their faith well. St. Innocent Veniaminov, first ruling bishop in North America and later Metropolitan of Moscow emphasized that “it is the binding duty of every Christian, when he reaches maturity, to know his faith thoroughly, because anyone who does not have a solid knowledge of his faith is cold and indifferent to it and frequently falls either into superstition or unbelief” (Indication of the Way into the Heavenly Kingdom). This great missionary bishop helps us to see that theology belongs to everyone who is a Christian. Therefore, it is up to those who have the gift of a formal theological education to cultivate interest and enthusiasm among those seeking Christ. For God “desires all to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth” (1 Tim. 2:4).

Just as theology must not be confined to the ivory tower, it also must not become a prisoner of sectarianism. It must not be strangled by an attitude or mind-set that understands and articulates the vision and life of the Church as it is seen though the cloudy lens of ignorance, fear and open antagonism to anything new, different or challenging to the status quo. We are Orthodox Christians living in the West in the 21st century and have no right to pretend that we live in Byzantium or pre-Revolutionary Russia. Both of these worlds are gone. And lest we forget, each of these worlds was fraught with its own inherent problems, heresies and biases.

Theology and Pastoral Care

Throughout this address I have stressed that theology belongs to all the faithful. Yet, because it is the parish priest who potentially has the most influence when it comes to teaching in a local church, I will limit my remarks to his vocation.

Theology and pastoral care cannot be separated. The theologian is pastor and the pastor is theologian. By virtue of his place within the Eucharistic community, the pastor is compelled to share the theology of the Church with his flock. Because the pastor lives and works within a specific community he cannot–must not–limit theology to his archives or to his desk. The pastor-theologian is to convey to the community of the faithful that theology leads one to God’s kingdom. The pastor-theologian is to be perceived as a servant who, like the Lord himself, takes on the struggles and burdens of those in his care. In his Great Catechism, St. Theodore the Studite refers to the heavy responsibility he carries due to those in his care. “For your salvation I have to deliver my frail soul, even shed my blood. According to the works of the Lord, this is the special function of the good and true shepherd. Struggles arise from this, and sadness and anxieties, preoccupation, sleeplessness and despondency.”

These difficult words of the Studite remind us that the pastor is to love and serve the other as he seeks to heal and save the other. In the realm of pastoral care, theology offers comfort and hope. Theology brings the dead to life and prepares the living for death. Theology draws the wounded back to the context of the Church’s worship where, in the context of the Divine Liturgy, everyone and everything acquires its proper identity in relationship to the Triune God. In the context of the Eucharistic celebration we are “endowed” here and now “with the Kingdom which is to come” (Chrysostom Liturgy).

So long as theology is experienced and taught as that which brings us into the Church–into the saving and transfiguring life in Christ–the missionary mandate will not be ignored or compromised. So long as theology is received as a gift that draws us into the ascetical arena, it will continue to build up and fortify the body of Christ.

Finally, so long as theology is accepted with thanks and in a spirit of humility, the divine uncreated light of the Godhead will continue to transform and deify the human person and his surroundings.

Thank you.

Fr. Robert Arida is the dean at Holy Trinity Cathedral in Boston, MA. He and his wife Susan also were teachers at the Seminary in the 1980s. Currently he serves on the Board of Trustees for the Seminary.