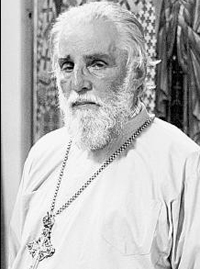

Archpriest Vladislav Sveshnikov

The Ladder

The reading from this Sunday’s Apostle (Eph 5:9-19) is extremely rich in meaning, both in spiritual terms and in terms of everyday life. However, it is sufficient for our purposes to look at just one meaning. The Apostle calls on us ‘to prove’, that is, to try to learn, what is acceptable to God, what is pleasing to God. For the believer, the aim is clear.

Briefly, if we do not try to learn, that is to study and to know, what is pleasing to God, then we cannot do it, because how can we do what we do not know? If we do not know what to do, there will just be chance hits, like those of a poor marksman aiming at a target: perhaps once he will hit the bull’s eye, the rest of the time he will fall wide of the mark. And if we do not do what we have to do, then how can we even call ourselves believers? He who does not do what is pleasing to God does not live for the faith, but lives for himself. The main task in the life of any believer must be to do God’s Will. Many people are astonished that their lives do not turn out well in. In reality, it is all very simple. Things do not turn out well precisely because we do not make God’s Will our priority and often do not even think about this at all, but about other things. Doing God’s Will does not figure as our aim in life, our aim in life is some purely personal, psychological matter, or else it is all to do with outward values, which have nothing whatsoever to do with God’s Will.

Why do we need to try and learn what is pleasing to God? The answer is plain and simple. It is because we cannot directly know or understand what is pleasing to God. If everything were plain and simple, there would be no need to occupy ourselves with that special activity which is called trying to learn, that is, studying. If everything were clear without trying to learn, then there would be nothing to study. But such attempts to learn are not a matter of studying texts written down in books – that would not be very complex either, especially if it were merely a matter of formally studying the Gospels and the Apostle. It is not enough simply to read the Gospels like a piece of information; the reading of the Gospel has to enter into our memories not just through our minds, but through our hearts as well. When knowledge enters into the memory through the heart, then it starts to ‘work’ in the human soul because the information of the heart forces us, as it were, to direct ourselves to inward activity. Until that moment, as long as what we have read remains in our passive memory, no inward activity can take place.

Reading and applying what we have read is already useful in itself, because it helps us to find out what God’s Will is. But that is not all that is contained in the concept of trying to learn what is ‘pleasing to God’. There is also a task which is almost technological in scope – this is redirecting our thought in such a way that we conform God’s Will, as it is expressed in the Gospels in a general sense for everyone, to our personal lives. In this respect it is above all vital to read attentively and apply what we have read to ourselves. Then much becomes clear, at least, for our repentance. When we try to learn God’s Will personally, we find out what God wants from us personally: what qualities we need in various circumstances, what course of action we must take, especially in dilemmas (including, for example, where we must go to work, if we are to leave a former job etc). And many other minor details of everyday life, especially when we are faced by dilemmas, require us to seek out God’s Will.

If human discernment is not focused on God’s Will, it will work on the basis of uncertainty, which is similar to solving dilemmas by casting lots. In order to seek out God’s Will for ourselves, to try to learn what ‘is pleasing to God’, there exists an exact science, practice and art which is called ascetic life. Everything that makes up this life – fasting, prayer, feats of repentance, the struggle against bad thoughts – is not important in itself, but important inasmuch as it brings the soul, mind and heart into a state in which firstly we begin to see what God’s Will is and secondly we begin to put it into practice.

Ascetic life (in particular, fasting) is indispensable, not simply because it is an established part of religious life and Church practice. When they brought the Lord the paralytic and epileptic youth who was possessed by a demon and who cast himself first into the fire, then into the water, the Lord said: ‘This kind goeth not out but by prayer and fasting’. This means that prayer and fasting are important, precisely because they are related to real life and the personal experience of each one of us, especially in one-off spiritual situations and in daily life. In this respect our Holy Orthodox Church has an unusual and vast stock of experience, unusual even for the Christian world in general, because the ascetic experience of Catholicism (for instance, its one-day fast) is virtually negligible when compared to the experience of the Orthodox Church. (As regards Protestantism, there is nothing to say). Even in the days when everyone was united in the Church, the basic ascetic aspects of life were discovered and lived in the East (as can be seen from the ascetic writings of the Fathers) and the West was occupied with other problems. The West, we can say, learned how to adapt to the world and adapt the world to it.

However, the experience of the Church in the East, even after the falling away of the West, is no less than what it was before the division, and was directed towards the highest ascetic activity – trying to learn what God’s Will is, to learn what is good, pleasing and perfect, and what it consists of, trying to learn what is ‘acceptable to God’, studying it, both generally and personally. The spiritual order of those who laboured the most in the Church in the East was directed precisely at this main task: the study of what God’s Will is. In this respect it is not a coincidence that this Sunday is dedicated to St John of the Ladder, who was one of those who toiled the most for this, one of those who not only studied but knew remarkably well how to transmit in writing this experience of the ascetic life in a general spiritual and moral framework.

This is why we are once more faced with the need to hymn the triumph of Orthodoxy, the triumph of ascetic experience as the experience of studying, trying to learn and doing God’s Will. Looking back from our present age, which has gradually risen to all sorts of achievements, to distant centuries, the third century (if we begin with St Antony the Great), the fourth, the fifth, the eighth, the fourteenth (St Gregory of Sinai), looking back to these distant centuries from our ‘great progress’, alas!, we have to admit that we are beggars. We are offered the gift of great riches and from these great riches we take, not only in practice, but even as a matter of study, in terms of book knowledge, an extremely small amount.

It is not a question, for example, of reading St John’s book ‘The Ladder’ as an ordinary piece of reading which provides information. The sense of addressing ourselves to ‘The Ladder’, as with any other ascetic literature, is all about reading it through the prism of our life, through the personal experience of our hearts. We have to go through all the rungs of the ladder with heartfelt feeling, but in life we stop only on the first rungs, but at least we do that thoroughly. Alas! Hardly anyone stops and so we have to accept a well-deserved reproach. But that reproach is only half the truth. The whole truth (and in our hearts we know that it is so) is in fact that the ascetic riches of Orthodox knowledge are our riches. Let the world weep, but we shall not weep such tears of shame, we shall weep with the blessed tears of repentance and heartfelt emotion, because the ascetic experience of the great fathers of ancient times teaches us these sentiments. Let the world weep because it not only does not know the beauty of ascetic life, but does not even want to know it!

I remember reading a conversation in the book about Elder Silouan. Some Non-Orthodox, probably a Catholic, was astonished that Orthodox monks read books which in the West only academic specialists read, and the monks get through dozens of them. To our great joy we can say that today, amid the ocean of Orthodox books that has unfurled, our new Russian Orthodox people, who have returned, perhaps not in great numbers, but they have still returned, to the Church, throw themselves greedily at ascetic literature first of all. Nothing is read with such absorbing interest as ascetic books, books written by ancient fathers and by spiritual writers closer to us in time. Thus it would seem that of nineteenth century authors the most read today are St Ignatius (Brianchaninov), St Theophan the Recluse and St John of Kronstadt, compilations of the ascetic experience of the ancient fathers. And it may be that in just our small church there are more people who read St Ignatius and ‘The Ladder’ than in all Catholic and Protestant Europe. Is this not the Triumph of Orthodoxy!

With bitter regret we will accept the well-deserved reproaches that our lives are quite, quite different from books, but many of today’s Orthodox Christians in Russia are only just beginning to live in Church ways. And if such saving ways are deemed fit for Russia, then they are possible because Russian Orthodox people, or at least the most responsible part of them, have to try to learn what is ‘acceptable to God’ and, as they learn, they will at least strive just a little to put into practice what they have learned in their attempts. For the moment there are not as many such people as we would like, but God is not in majorities, He is in truth. These people – the small flock, but I think an interesting layer of the population, thin like a film of oil compared to the depths of the ocean, will turn out to be more viable than the un-Orthodox majority, remembering that all sorts of weaknesses, physical, spiritual and emotional, can be found in many Orthodox people. But it is precisely this layer of people who keep in themselves the intuitive sense of the vital need to seek out God’s Will, even if they do not always realize this.

And because this responsible layer lives and breathes, God keeps this decaying old world from its inevitable collapse. Otherwise it would in all probability long ago have started to fall apart. Our seemingly tiny and insignificant ascetic life is perhaps in the eyes of God not completely insignificant and our small, almost invisible sacrifice is not without meaning in His eyes. Glory to God Who has allowed us, in the words of the poet, to visit ‘this world in its moments of destiny’. Glory to God, because prayer and fasting and other ascetic acts are carried out and justified by life itself. As sailors used to say: ‘He who has not been to sea has not prayed’. Today we sail in a stormy sea and life calls us to all sorts of ascetic life because otherwise, as is obvious, we will perish. And yet all the same for contemporary people ascetic life is still wishful thinking rather than real. And realizing this fact with bitter regret we understand that it is for precisely this reason that we have no justification at all for self-satisfaction. Glory to God, if we rely on our own efforts and their self-created abilities we will perish. And the waves of the sea of life sweep us along and because of the likelihood that we shall perish, all we can do is cry out in fear and trembling: ‘Lord, save us, we perish!’ But at the same time we realize with joy that these cries come into being according to specific ascetic rules and this means that God’s Will is in them and, inasmuch as that, our cries become new signs of our ascetic triumph. Of course, our triumph as ever has an aftertaste of bitter regret and that is why we cry out with repentance. But nobody can ever take away this triumph from us because this triumph is more than personal, this is the triumph of Orthodoxy, of which by God’s mercy we all partake.

Translated from Russian by Fr. Andrew Phillips