Source: Saint Paul’s Greek Orthodox Church

Obedience and freedom

Such are, by God’s grace, the gifts of the starets. But what of the spiritual child? How does he or she contribute to the mutual relationship between guide and disciple?

Briefly, what the disciple offers is sincere and willing; obedience. As a classic example, there is the story in the Sayings of the Desert Fathers about the monk who was told to plant a dry stick in the sand and to water it daily. So distant was the spring from his cell that he had to leave in the evening to fetch the water and he only returned in the following morning. For three years he patiently fulfilled his abba’s command. At the end of this period, the stick suddenly put forth leaves and bore fruit. The abba picked the fruit, took it to the church, and invited the monks to eat, saying, “Take and eat the fruit of obedience.”1]

Another example of obedience is the monk Mark, who while copying a manuscript was suddenly called by his abba; so immediate was his response that he did not even complete the circle of the letter O that he was writing. On another occasion, as they walked together, his abba saw a small pig; testing Mark, he said, “Do you see that buffalo, my child?” “Yes, father,” replied Mark. “And you see how elegant its horns are?” “Yes, father,” he answered once more without demur.[2] Abba Joseph of Panepho, following a similar policy, tested the obedience of his disciples by assigning paradoxical and even scandalous tasks, and only if they complied would he then give them sensible commands.[3] Another geron instructed his disciple to steal things from the cells of the brethren;[4] yet another told his disciple (who had not been entirely truthful with him) to throw his son into the furnace.[5]

At this point it is surely necessary to state clearly certain serious objections. Stories of the kind that we have just reported are likely to make a deeply ambivalent impression upon a modern reader. Do they not describe the kind of behavior that we may perhaps reluctantly admire but would scarcely wish to imitate? What has happened, we may ask with some indignation, to “the glorious liberty of the children of God” (Rom 8:21)?

Few of us would doubt the value of seeking guidance from someone else, whether man or woman, who has a greater experience than we do of the spiritual way. But should such a person be treated as an infallible oracle, whose every word is to be obeyed without any further discussion? To interpret the mutual relationship between the disciple and the spiritual mother or father in such a manner as this seems dangerous for both of them. It reduces the disciple to an infantile and even subhuman level, depriving her or him of all power of judgment and moral choice; and it encourages the teacher to claim an authority which belongs to God alone. Earlier we quoted the statement from the Sayings of the Desert Fathers that someone under obedience to an elder “has no need to attend to the commandment of God.”[6] But is such an abdication of responsibility desirable? Should the geronta be allowed to usurp the place of Christ?

In response, it needs to be said first of all that “charismatic” elders, such as St Anthony the Great or St Seraphim of Sarov, have always been exceedingly rare. The kind of relationship that they had with their disciples, whether monastic or lay, has never been the standard pattern in the Orthodox tradition. The great startsi, whether of the past or of the present day, do indeed constitute a guiding light, a supreme point of reference; but they are the exception, not the norm.

In the second place, there is clearly a difference between monastics, who have taken a special vow of obedience, and lay people who are living in the “world.” (Even in the case of monastics, there are extremely few communities where the ministry of eldership is to be found in its full form, as described in the Sayings of the Desert Fathers or as practiced in nineteenth-century Optino.) A contemporary Russian priest, Father Alexander Men — himself much revered as a spiritual father before his tragic and untimely death at unknown hands in 1990 — has wisely insisted that monastic observances cannot be transferred wholesale to parish life: “We often think that the relation of spiritual child to spiritual father requires that the former be always obedient to the latter. In reality, this principle is an essential part of the monastic life. A monk promises to be obedient, to do whatever his spiritual father requires. A parish priest cannot impose such a model on lay people and cannot arrogate to himself the right to give peremptory orders. He must be happy recalling the Church’s rules, orienting his parishioner’s lives, and helping them in their inner struggles.” [7]

In the second place, there is clearly a difference between monastics, who have taken a special vow of obedience, and lay people who are living in the “world.” (Even in the case of monastics, there are extremely few communities where the ministry of eldership is to be found in its full form, as described in the Sayings of the Desert Fathers or as practiced in nineteenth-century Optino.) A contemporary Russian priest, Father Alexander Men — himself much revered as a spiritual father before his tragic and untimely death at unknown hands in 1990 — has wisely insisted that monastic observances cannot be transferred wholesale to parish life: “We often think that the relation of spiritual child to spiritual father requires that the former be always obedient to the latter. In reality, this principle is an essential part of the monastic life. A monk promises to be obedient, to do whatever his spiritual father requires. A parish priest cannot impose such a model on lay people and cannot arrogate to himself the right to give peremptory orders. He must be happy recalling the Church’s rules, orienting his parishioner’s lives, and helping them in their inner struggles.” [7]

Yet, when full allowance has been made for these two points, there are three further things that need to be said if a text such as the Sayings of the Desert Fathers or a figure such as Starets Zosima in The Brothers Karamazov are to be interpreted aright. First, the obedience offered by the spiritual child to the abba is not forced but willing and voluntary. It is the task of the starets to take up our will into his will, but he can only do this if by our own free choice we place it in his hands. He does not break our will, but accepts it from us as a gift. A submission that is forced and involuntary is obviously devoid of moral value; the starets asks of each one that we offer to God our heart, not our external actions. Even in a monastic context the obedience is voluntary, as is vividly emphasized at the rite of monastic profession: only after the candidate has three times placed the scissors in the abbot’s hand does the latter proceed to tonsure him.

This voluntary offering of our freedom, however, even in a monastery, is obviously something that cannot be made once and for all, by a single gesture. We are called to take up our cross daily (Luke 9:23). There has to he a continual offering, extending over our whole life; our growth in Christ is measured precisely by the increasing degree of our self-giving. Our freedom must be offered anew each day and each hour, in constantly varying ways; and this means that the relation between starets and disciple is not static but dynamic, not unchanging but infinitely diverse. Each day and each hour, under the guidance of his abba, the disciple will face new situations, calling for a different response, a new kind of self-giving.

In the second place, the relation between starets and spiritual child, as we have already noted, is not one-sided, but mutual. Just as the starets enables the disciples to see themselves as they truly are, so it is the disciples who reveal the starets to himself. In most instances, someone does not realize that he is called to be a starets until others come to him and insist on placing themselves under his guidance. This reciprocity continues throughout the relationship between the two. The spiritual father does not possess an exhaustive program, neatly worked out in advance and imposed in the same manner upon everyone. On the contrary, if he is a true starets, he will have a different word for each; he proceeds on the basis not of abstract rules but of concrete human situations. He and his disciple enter each situation together, neither of them knowing beforehand exactly what the outcome will be, but each waiting for the illumination of the Spirit. Both of them, the spiritual father as well as the disciple, have to learn as they go.

The mutuality of their relationship is indicated by stories in the Sayings of the Desert Fathers where an unworthy abba is saved through the patience and humility of his disciple. A brother, for example, has an elder who is given to drunkenness, and is sorely tempted to leave him; but, instead of doing so, he remains faithfully with his abba until the latter is eventually brought to repentance. As the narrator comments, “Sometimes it is the young who guide their elders to life.”[8] The disciple may be called to give as well as to receive; the teacher may often learn from his pupils. As the Talmud records, “Rabbi Hanina used to say, ‘Much have I learnt from my teachers, more from my fellowstudents, but from my pupils most of all.'”[9]

In reality, however, the relationship is not two-sided but triangular, for in addition to the abba and his disciple there is also a third partner, God. Our Lord insisted that we should call no one “father,” for we have only one Father, who is in heaven (Mt 13:8-10). The abba is not an inerrant judge or an ultimate court of appeal, but a fellow-servant of the living God; not a tyrant, but a guide and companion on the way. The only true “spiritual director,” in the fullest sense of the word, is the Holy Spirit.

This brings us to the third point. In the Orthodox tradition at its best, spiritual guides have always sought to avoid any kind of constraint and spiritual violence in their relations with their disciples. If, under the guidance of the Spirit, they speak and act with authority, it is with the authority of humble love. Anxious to avoid all mechanical constraint, they may sometimes refuse to provide their disciples with a rule of life, a set of external commands to be applied automatically. In the words of a contemporary Romanian monk, the spiritual father is “not a legislator but a mystagogue.”[10] He guides others, not by imposing rules, but by sharing his life with them. A monk told Abba Poemen, “Some brethren have come to live with me; do you want me to give them orders?” “No,” said the old man. “But, Father,” the monk persisted, “they themselves want me to give them orders.” “No,” repeated Poemen, “be an example to them but not a lawgiver.”[11] The same moral emerges from a story told by Isaac the Priest. As a young man, he remained first with Abba Kronios and then with Abba Theodore of Pherme; but neither of them told him what to do. Isaac complained to the other monks and they came and remonstrated with Theodore.

“If he wishes,” Theodore replied eventually, “let him do what he sees me doing.”[12] When Barsanuphius was asked to supply a detailed rule of life, he declined, saying: “I do not want you to be under the law, but under grace.” And in other letters he wrote: “You know that we have never imposed chains upon anyone… Do not force people’s free will, but sow in hope; for our Lord did not compel anyone, but He preached the good news, and those who wished hearkened to Him.”[13]

Do not force people’s free will. The task of our spiritual father is not to destroy our freedom, but to assist us to see the truth for ourselves; not to suppress our personality, but to enable us to discover our own true self, to grow to full maturity and to become what we really are. If on occasion the spiritual father requires an implicit and seemingly “blind” obedience from his disciple, this is never done as an end in itself, nor with a view to enslaving him. The purpose of this kind of “shock treatment” is simply to deliver the disciple from his false and illusory “self,” so that he may enter into true liberty; obedience is in this way the door to freedom. The spiritual father does not impose his personal ideas and devotions, but he helps the disciple to find his own special vocation. In the words of a seventeenth-century Benedictine, Dom Augustine Baker: “The director is not to teach his own way, nor indeed any determinate way of prayer, but to instruct his disciples how they may themselves find out the way proper for them… In a word, he is only God’s usher, and must lead souls in God’s way, and not his own.”[14]

Such was also the approach of Father Alexander Men. In the words of his biographer Yves Hamant, “Father Alexander wanted to lead each person to the point of deciding for himself; he did not want to order or to impose. He compared his role to that of a midwife who is present only to help the mother give birth herself to her baby. One of his friends wrote that Father Alexander was ‘above us yet right beside us.'”[15]

In the last resort, then, what the spiritual mother or father gives to the disciple is not a code of written or oral regulations, not a set of techniques for meditation, but a personal relationship. Within this personal relationship the abba grows and changes as well as the disciple, for God is constantly directing them both. The abba may on occasion provide his disciple with detailed verbal instructions, with precise answers to specific questions. On other occasions he may fail to give any answer at all, either because he thinks that the question does not need an answer, or because he himself does not yet know what the answer should be. But these answers — or this failure to answer — are always given within the framework of a personal relationship. Many things cannot be said in words, but can only be conveyed through a direct personal encounter. As the Hasidic master Rabbi Jacob Yitzhak affirmed, “The way cannot be learned out of a book, or from hearsay, but can only be communicated from person to person.”[16]

Here we touch on the most important point of all, and that is the personalism that inspires the encounter between disciple and spiritual guide. This personal contact protects the disciple against rigid legalism, against slavish submission to the letter of the law. He learns the way, not through external conformity to written rules, but through seeing a human face and hearing a living voice. In this way the spiritual mother or father is the guardian of evangelical freedom.

In the absence of a starets

And what are we to do, if we cannot find a spiritual guide? For, as we have noted, guides such as St Antony or St Seraphim are few and far between.

We may turn, in the first place, to books. Writing in fifteenth-century Russia St Nil Sorsky laments the extreme scarcity of qualified spiritual directors; yet how much more frequent they must have been in his day than in ours! Search diligently, he urges, for a sure and trustworthy guide. Then he continues: “However, if such a teacher cannot be found, then the Holy Fathers order us to turn to the Scriptures and listen to our Lord Himself speaking.”[17] Since the testimony of Scripture should never be isolated from the continuing witness of the Spirit in the life of the Church, we may add that the inquirer will also want to read the works of the Fathers, and above all the Philokalia. But there is an evident danger here. The starets adapts his guidance to the inner state of each; books offer the same advice to everyone. How are we to discern whether or not a particular text is applicable to our own situation? Even if we cannot find a spiritual father in the full sense, we should at least try to find someone more experienced than ourselves, able to guide us in our reading.

It is possible to learn also from visiting places where divine grace has been exceptionally manifest and where, in T S. Eliot’s phrase, “prayer has been valid.” Before making a major decision, and in the absence of other guidance, many Orthodox Christians will go on pilgrimage to Jerusalem or Mount Athos, to some monastery or the shrine of a saint, where they will pray for illumination. This is the way in which I myself have reached certain of the more difficult decisions in my life.

Thirdly, we can learn from religious communities with an established tradition of the spiritual life. In the absence of a personal teacher, the monastic environment can itself serve as abba; we can receive our formation from the ordered sequence of the daily program, with its periods of liturgical and silent prayer, with its balance of manual labor, study and recreation. This seems to have been the chief way in which St Seraphim of Sarov gained his spiritual training. A well-organized monastery embodies, in an accessible and living form, the inherited wisdom of many startsi. Not only monks but those who come as visitors, remaining for a longer or shorter period, can be formed and guided by the experience of community life.

It is indeed no coincidence that, when the kind of “charismatic” spiritual fatherhood that we have been describing first emerged in fourth century Egypt, this was not within the fully organized communities under St Pachomius, but among the hermits and in the semieremitic milieu of Nitria and Scetis. In the Pachomian koinonia, spiritual direction was provided by Pachomius himself, by the superiors of each monastery, and by the heads of individual “houses” within the monastery. The Rule of St Benedict also envisages the abbot as spiritual father, and there is virtually no provision for further direction of a more “charismatic” type.[18] In time, it is true, the cenobitic communities incorporated many of the traditions of spiritual fatherhood as developed among the hermits, but the need for those traditions has always been less intensely felt in the cenobia, precisely because direction is provided by the corporate life pursued under the guidance of the monastic rule.

Finally, before leaving this question of the absence of a starets, it is important for us to emphasize the extreme flexibility in the relationship between spiritual guide and disciple. Some may see their spiritual guide daily or even hourly, praying, eating and working with him, perhaps sharing the same cell, as often happened in the Egyptian desert. Others may see him only once a month or once a year; others, again, may visit an abba on but a single occasion in their entire life, yet this will be sufficient to set them on the right path. There are, furthermore, many different types of spiritual father or mother; few will be wonderworkers like St Seraphim of Sarov. There are numerous priests and laypeople who, while lacking the more spectacular endowments of the famous startsi, are certainly able to provide others with the guidance that they require. Furthermore, let us never forget that, alongside spiritual fatherhood and motherhood, there is also spiritual brotherhood and sisterhood. At school or university we often learn more from our fellow students than from our teachers; and the same may happen also in our life of prayer and inner exploration.

When people imagine that they have failed in their search for a guide, often this is because they expect him or her to be of a particular type; they want a St Seraphim, and so they close their eyes to the guides whom God is actually sending to them. Often their supposed problems are not so very complicated, and in reality they already know in their own heart what the answer is. But they do not like the answer, because it involves patient and sustained effort on their part; and so they look for a deus ex machina who, by a single miraculous word, will suddenly make everything easy. Such people need to be helped to an understanding of the true nature of spiritual direction.

Contemporary examples

In conclusion, I wish to recall two elders of our own day, whom I have had the privilege and happiness of knowing personally. The first is Father Amphilochios (✝1970), at one time abbot of the Monastery of St John on the Island of Patmos, and subsequently geronta to a community of nuns which he had founded not far from the Monastery. What most distinguished his character was his gentleness, his humor, the warmth of his affection, and his sense of tranquil yet triumphant joy. His smile was full of love, but devoid of all sentimentality. Life in Christ, as he understood it, is not a heavy yoke, a burden to be carried with sullen resignation, but a personal relationship to be pursued with eagerness of heart. He was firmly opposed to all spiritual violence and cruelty. It was typical that, as he lay dying and took leave of the nuns under his care, he should urge the abbess not to be too severe on them: “They have left everything to come here, they must not be unhappy.”[19]

In conclusion, I wish to recall two elders of our own day, whom I have had the privilege and happiness of knowing personally. The first is Father Amphilochios (✝1970), at one time abbot of the Monastery of St John on the Island of Patmos, and subsequently geronta to a community of nuns which he had founded not far from the Monastery. What most distinguished his character was his gentleness, his humor, the warmth of his affection, and his sense of tranquil yet triumphant joy. His smile was full of love, but devoid of all sentimentality. Life in Christ, as he understood it, is not a heavy yoke, a burden to be carried with sullen resignation, but a personal relationship to be pursued with eagerness of heart. He was firmly opposed to all spiritual violence and cruelty. It was typical that, as he lay dying and took leave of the nuns under his care, he should urge the abbess not to be too severe on them: “They have left everything to come here, they must not be unhappy.”[19]

Two things in particular I recall about him. The first was his love of nature and, more especially, of trees. “Do you know,” he used to say, “that God gave us one more commandment, which is not recorded in Scripture? It is the commandment Love the trees.” Whoever does not love trees, he was convinced, does not love Christ. When hearing the confessions of the local farmers, he assigned to them as a penance (epitimion) the task of planting a tree; and through his influence many hill-sides of Patmos, which once were barren rock, are now green with foliage every summer.[20]

A second thing that stands out in my memory is the counsel which he gave me when, as a newly-ordained priest, the time had come for me to return from Patmos to Oxford, where I was to begin teaching in the university. He himself had never visited the west, but he had a shrewd perception of the situation of Orthodoxy in the diaspora. “Do not be afraid,” he insisted. Do not be afraid because of your Orthodoxy, he told me; do not be afraid because, as an Orthodox in the west, you will be often isolated and always in a small minority. Do not make compromises but do not attack other Christians; do not be either defensive or aggressive; simply be yourself.

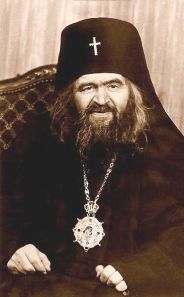

My second example of a twentieth-century starets known to me personally is St John Maximovitch (✝1966), Russian bishop in Shanghai, then in Western Europe, and finally in San Francisco. Little more than a dwarf in height, with tangledhair and beard, and with an impediment in his speech, at first sight he seemed to possess more than a touch of the “fool in Christ.” From the time of his profession as a monk, except when ill he did not lie down on a bed; he went on working and praying all night, snatching his sleep at odd moments in the twenty-four hours. He wandered barefoot through the streets of Paris, and once he celebrated a memorial service in the port of Marseilles on the exact spot where King Alexander of Yugoslavia had been assassinated, in the middle of the road among the tram lines. Punctuality had little meaning for him. Baffled by his behavior, the more conventional among his flock judged him unsuited for the public position and the administrative work of a bishop. But, if unpredictable, he was also practical and realistic. With his total disregard of normal formalities he succeeded where others, relying on worldly influence and expertise, had failed entirely — as when, against all hope and in the teeth of the “quota” system, he secured the admission of thousands of homeless Russian refugees to the USA.

My second example of a twentieth-century starets known to me personally is St John Maximovitch (✝1966), Russian bishop in Shanghai, then in Western Europe, and finally in San Francisco. Little more than a dwarf in height, with tangledhair and beard, and with an impediment in his speech, at first sight he seemed to possess more than a touch of the “fool in Christ.” From the time of his profession as a monk, except when ill he did not lie down on a bed; he went on working and praying all night, snatching his sleep at odd moments in the twenty-four hours. He wandered barefoot through the streets of Paris, and once he celebrated a memorial service in the port of Marseilles on the exact spot where King Alexander of Yugoslavia had been assassinated, in the middle of the road among the tram lines. Punctuality had little meaning for him. Baffled by his behavior, the more conventional among his flock judged him unsuited for the public position and the administrative work of a bishop. But, if unpredictable, he was also practical and realistic. With his total disregard of normal formalities he succeeded where others, relying on worldly influence and expertise, had failed entirely — as when, against all hope and in the teeth of the “quota” system, he secured the admission of thousands of homeless Russian refugees to the USA.

In private conversation he was abrupt yet kindly. He quickly won the confidence of small children. Particularly striking was the intensity of his intercessory prayer. It was his practice, whenever possible, to celebrate the Divine Liturgy daily, and the service often took twice the normal space of time, such was the multitude of those whom he commemorated individually by name. As he prayed for them, they were never mere entries on a list, but always persons. One story that I was told is typical. It was his custom each year to visit Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, NY. As he made his departure after one such visit, a monk gave him a slip of paper with four names of those who were gravely ill. St John received thousands upon thousands of such requests for prayer in the course of each year. On his return to the monastery some twelve months later, at once he beckoned to the monk and, much to the latter’s surprise, from the depths of his cassock St John produced the identical slip of paper, now crumpled and tattered. “I have been praying for your friends,” he said, “but two of them” — he pointed to their names — “are now dead, while the other two have recovered.” And so indeed it was.

Even at a distance he shared in the concerns of his spiritual children. One of them, Father (later Archbishop) Jacob, superior of a small Orthodox monastery in Holland, was sitting at a late hour in his room, unable to sleep from anxiety over the financial and other problems which faced him. In the middle of the night the phone rang; it was St John, speaking from several hundred miles away. He had telephoned to say that it was time for Father Jacob to go to bed: “Go to sleep now, what you are asking of God will certainly be all right.”[21]

Such is the role of the spiritual father. As St Barsanuphius expressed it, “I care for you more than you care for yourself.”

[1] AP, alphabetical collection, John the Dwarf i (2o4e); tr. Ward, Sayings, 85-86.

[2] AP, alphabetical collection, Mark the Disciple of Silvanus 1, 2 (293D-296B); tr., 145-46.

[3] Ibid., Joseph of Panepho 5 (229BC); tr., 103.

[4] Ibid., Saio i (420AB); tr., 229. The geron subsequently returned the things to their rightful owners.

[5] AP, anonymous series 295: ed. Nau, ROC14 (1909), 378; tr. Ward, Wisdom, §162,(47). Miraculously the child was preserved unharmed. For a parallel story, see AP, alphabetical collection, Sisoes 10 (394C-396A); tr. Ward, Sayings, 214; and compare Abraham and Isaac (Gen 22).

[6] See above, first section.

[7] Quoted in Yves Harnant, Alexander Men: A Witness for Contemporary Russia (Torrance, CA: Oakwood Publications, 1995), 124.

[8] AP, anonymous collection 340: ed. Nau, ROC 17 (1912), 295; tr. Ward, Wisdom, §209 (56-57).

[9] C. G. Montefiore and H. Loewe (ed.), A Rabbinic Anthology (London: Macmillan,1938), §494.

[10] Father Andrй Scrima, “La tradition du pиre spirituel dans l’Йglise d’Orient,”Hermиs, 1967, No. 4, 83.

[11] AP, alphabetical collection, Poemen 174 (364C); tr. Ward, Sayings, 191.

[12] Ibid., Isaac the Priest 2 (224CD); tr., 99-100.

[13] Questions and Answers, §§25,51,35.

[14] Quoted by Thomas Merton, Spiritual Direction and Meditation (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1960), 12.

[15] Alexander Men, 124.

[16] Buber, Tales of the Hasidim: The Early Masters, 256.

[17] “The Monastic Rule,” in G. P. Fedotov, A Treasury of Russian Spirituality (London: Sheed & Ward, 1950), 95-96.

[18] Except that in the Rule, §46, it is said that monks may confess their sins in confidence, not necessarily to the abbot, but to one of the senior monks possessing spiritual gifts (tantum abbati, aut spiritalibus senioribus).

[19] See I. Gorainoff, “Holy Men of Patmos,” Sobornost 6:5 (1912), 341-44.

[20] See my lecture, Through the Creation to the Creator, 5.

[21] Bishop Sawa of Edmonton, Blessed John: The Chronicle of the Veneration of Archbishop John Maximovich (Platina, CA: Saint Heman of Alaska Brotherhood, 1979),104; Father Seraphim Rose and Abbot Herman, Blessed John the Wonderworker. A Preliminary Account of the Life and Miracles of Archbishop John Maximovitch, 3rd edn. (Plating, CA: Saint Herman of Alaska Brotherhood,

1987), 163. I heard the story from Father Jacob himself.