Source: Saint Paul’s Greek Orthodox Church

The three gifts of the spiritual guide

The three gifts of the spiritual guide

Three gifts in particular distinguish the spiritual guide. The first is insight and discernment (diakrisis), the ability to perceive intuitively the secrets of another’s heart, to understand the hidden depths of which the other does not speak and is usually unaware. The spiritual father or mother penetrates beneath the conventional gestures and subterfuges whereby we conceal our true personality from others and from ourselves; and, beyond all these trivialities, she or he comes to grips with the unique person made in the image and likeness of God. This power of discernment is spiritual rather than psychic; it is not simply a happy knack of hitting the nail on the head, nor yet a kind of extrasensory perception or clairvoyance, but it is the fruit of grace, presupposing concentrated prayer and an’ unremitting ascetic struggle.

With this gift of insight there goes the ability to use words with power. As each person comes before him, the starets or geronta knows immediately and specifically what it is that this particular individual needs to hear. Today, by virtue of computers and photocopying machines, we are inundated with words as never before in human history; but alas! for the most part these are conspicuously not words uttered with power.[1] The starets, on the other hand, uses few words, and sometimes none at all; but, by these few words or by his silence, he is often able to alter the entire direction of another’s life. At Bethany Christ used three words only: “Lazarus, come out” (Jn 11:43); and yet these three words, spoken with power, were sufficient to bring the dead back to life. In an age when language has been shamefully trivialized, it is vital to rediscover the power of the word; and this means rediscovering the nature of silence, not just as a pause in the midst of our talk, but as one of the primary realities of existence. Most teachers and preachers surely talk far too much; the true starets is distinguished by an austere economy of language.[2]

Yet, for a word to possess power, it is necessary that there should be not only one who speaks with the genuine authority of personal experience, but also one who listens with attention and eagerness. If we question a geronta out of idle curiosity, it is likely that we will receive little benefit; but if we approach him with ardent faith and deep hunger, the word that we hear may transfigure our whole being. The words of the startsi are for the most part simple in verbal expression and devoid of literary artifice; to those who read them in a superficial way, they will seem jejune and banal.

The elder’s gift of insight is exercised primarily through the practice known as the “disclosure of thoughts” (logismoi). In early Eastern monasticism the young monk used to go daily to his spiritual father and lay before him all the thoughts which had come to him during the day. This disclosure of thoughts includes far more than a confession of sins, since the novice also speaks of those ideas and impulses which may seem innocent to him, but in which the spiritual father may discern secret dangers or significant signs. Confession is retrospective, dealing with sins that have already occurred; the disclosure of thoughts, on the other hand, is prophylactic, for it lays bare our logismoi before they have led to sin and so deprives them of their power to harm. The purpose of the disclosure is not juridical, to secure absolution from guilt, but its aim is self-knowledge, that we may see ourselves as we truly are.

The principle underlying the disclosure of thoughts is clearly summed up in the Sayings of the Desert Fathers: “If unclean thoughts trouble you, do not hide them but tell them at once to your spiritual father and condemn them. The more we conceal our thoughts, the more they multiply and gain strength… [But] once an evil thought is revealed, it is immediately dissipated… Whoever discloses his thoughts is quickly healed.”[3]

If we cannot or will not bring out into the open a logismos, a secret fantasy or fear or temptation, then it possesses power over us. But if with God’s help and with the assistance of our spiritual guide, we bring the thought out from the darkness into the light, its influence begins to wither away. Having exposed the logismos, we are then in a position to deal with it, and the process of healing can begin. The method proposed here by the early monks has interesting similarities with the techniques of modern psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. But the early monks had worked out this method fifteen centuries before Freud and Jung! There is, of course, an important difference: the early monks did not employ the notion of the unconscious in the way that modern psychology does, even though they recognized that with our conscious understanding we are usually aware of only a small part of ourselves.

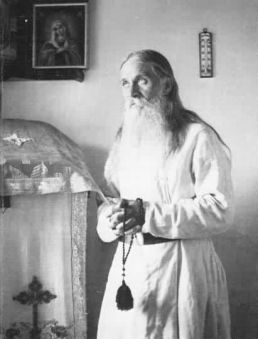

Endowed as he is with discernment, the spiritual father does not merely wait for a person to reveal himself, but takes the initiative in revealing to the other many thoughts of which the other is not yet aware. When people came to St Seraphim of Sarov, he often answered their difficulties before they had time to put their perplexities before him. On many occasions the answer at first seemed quite irrelevant, and even absurd and irresponsible; for what St Seraphim answered was not the question his visitor had consciously in mind, but the one which the visitor ought to have been asking. In all this St Seraphim relied on the inner light of the Holy Spirit. He found it important, he explained, not to work out in advance what he was going to say; in that case, his words would represent merely his own human judgment, which might well be in error, and not the judgment of God.[4]

In St Seraphim’s eyes, the relationship between starets and spiritual child is stronger even than death, and he therefore urged his children to continue their disclosure of thoughts to him after his departure to the next life. These are the words which, by his own instructions, were written on his tomb: “When I am no more, come to me at my grave, and the more often, the better. Whatever weighs on your soul, whatever may have happened to you, whatever sorrows you have, come to me as if I were alive and, kneeling on the ground, cast all your bitterness upon my grave. Tell me everything and I shall listen to you, and all the sorrow will fly away from you. And as you spoke to me when I was alive, do so now. For to you I am alive, and I shall be forever.”[5]

The second gift of the spiritual father or mother is the ability to love others and to make others’ sufferings their own. Of one elder mentioned in the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, it is briefly and simply recorded: “He possessed love, and many came to him.”[6] He possessed love — this is indispensable in all spiritual motherhood and fatherhood. Insight into the secrets of people’s hearts, if devoid of loving compassion, would not be creative but destructive; if we cannot love others, we will have little power to heal them.

Loving others involves suffering with and for them; such is the literal sense of the word “compassion.” “Bear one another’s burdens, and so fulfill the law of Christ” (Gal 6:2): the spiritual father or mother is the one par excellence who bears the burdens of others. “A starets,” writes Dostoevsky in The Brothers Karamazov, “is one who takes your soul, your will into his soul and into his will.”[7] It is not enough for him merely to offer advice in a detached way. He is also required to take up the soul of his spiritual children into his own soul, their life into his life. It is his task to pray for them, and his constant intercession on their behalf is more important to them than any words of counsel.[8] It is his task likewise to assume their sorrows and their sins, to take their guilt upon himself, and to answer for them at the Last Judgment. St Barsanuphius of Gaza insists to his spiritual children, “As God Himself knows, there is not a second or an hour when I do not have you in my mind and in my prayers… I take upon myself the sentence of condemnation against you, and by the grace of Christ, I will not abandon you, either in this age or in the Age to come.”[9] In the words of Dostoevsky’s starets Zosima, “There is only one way of salvation, and that is to make yourself responsible for the sins of all … to make yourself responsible in all sincerity for everything and everyone.”[10] The ability of the elder to support and strengthen others is measured exactly by the extent of his willingness to adopt this way of salvation.

Yet the relation between the spiritual father and his children is not one-sided. Though he takes the burden of their guilt upon himself and answers for them before God, he cannot do this effectively unless they themselves are struggling wholeheartedly on their own behalf. Once a brother came to St Antony of Egypt and said: “Pray for me.” But the old man replied: “Neither will I take pity on you nor will God, unless you make some effort of your own.”[11]

When considering the love of the guide for the disciple, it is important to give full meaning to the word “father” or “mother” in the title “spiritual father” or “spiritual mother.” As the father and mother in an ordinary family are joined to their offspring in mutual love, so it should also be within the “charismatic” family of the elder. Needless to say, since the bond between elder and disciples is a relationship not according to the flesh but in the Holy Spirit, the wellspring of human affection, without being ruthlessly repressed, has to be transfigured; and this transfiguration may sometimes take forms which, to an outside observer, seem somewhat inhuman. It is recounted, for example, how a young monk looked after his elder, who was gravely ill, for twelve years without interruption. Never once in that period did his elder thank him or so much as speak one word of kindness to him. Only on his death-bed did the old man remark to the assembled brethren, “He is an angel and not a man.”[12] Such stories are valuable as an indication of the need for spiritual detachment, but they are hardly typical. An uncompromising suppression of all outward tokens of affection is not characteristic of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, still less of the two Old Men of Gaza, Barsanuphius and John.

A third gift of the spiritual father and mother is the power to transform the human environment, both the material and the non-material. The gift of healing, possessed by so many of the startsi, is one aspect of this power. More generally, the starets helps his disciples to perceive the world as God created it and as God desires it once more to be. The true elder is one who discerns the universal presence of the Creator throughout creation, and assists others to discern it likewise. He brings to pass, in himself and in others, the transformation of which William Blake speaks: “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite.”[13] For the one who dwells in God, there is nothing mean and trivial: he or she sees everything in the light of Mount Tabor. A momentary glimpse of what this signifies is provided in the account by Nicolas Motovilov of his conversation with St Seraphim of Sarov, when Nicolas saw the face of the starets shining with the brilliancy of the mid-day sun, while the blinding light radiating form his body illuminated the snow-covered trees of the forest glade around them.[14]

[1] If the chairmen of committees and others in seats of authority were forced to write out personally in longhand everything they wanted to communicate, might they not choose their words with greater care?

[2] See the perceptive discussion in Douglas Burton-Christie, The Word in the Desert: Scripture and the Quest for Holiness in Early Christian Monasticism (New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), especially chapter 5; and compare Max Picard, The World of Silence (London: Flarvill Press, n.d.).

[3] For the Greek text of this apophthegma, see Evergetinos 1.20.11, ed. Victor Matthaiou, 4 vols. (Athens: Monastery of the Transfiguration of the Savior at Kronize Kouvara, 1957-66), 1:168-9; French translation in Lucien Regnault (ed.), Les Sentences des Pиres du Dйsert, serie des anonymes (Sablй-sur-Sarthe/Bйgrolles: Solesmes/Bellefontainc, 1985), 227.

[4] Archimandrite Lazarus Moore, St. Seraphim of Sarov, 217-20.

[5] Op. cit., 436-7.

[6] AP, alphabetical collection, Poemen 8 (321C); tr. Ward Sayings, 167.

[7] The Brothers Karamazov, tr. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (New York: Vintage Classics, 1991), 27.

[8] See, for example, the story in AP, anonymous collection 293: ed. Nau, ROC 14 (1909), 377; tr. Ward, Wisdom, §16o (45-46). The monk is delivered

[9] Questions andAnswers, ed. Schoinas §§208, 239; tr. Regnault and Lemaire, §§113, 239. On the spiritual father as burden-bearer, see above, 119-20, especially the quotations from Barsanuphius. In general, the 850 questions and answers that make up the Book of Barsanuphius and John show us, with a vividness not to be found in any other ancient source, exactly how the ministry of pastoral guidance was exercised in the Christian East.

[10] The Brothers Karamazov, tr. Pevear and Volokhonsky, 320.

[11] AP, alphabetical collection, Antony 16 (8oc); tr. Ward, Sayings, 4.

[12] AP, alphabetical collection, John the Theban 1 (240A); tr. Ward, Sayings, 109.

[13] “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell,” in Geoffrey Keynes (ed.), Poetry and Prose of William Blake (London: Nonesuch Press, 1948), 187.

[14] “A Wonderful Revelation to the World,” in Archimandrite Lazarus Moore, St. Seraphim of Sarov, 197.