Fr. Alexander Schmemann famously said that sacraments do not make things into something else so much as they reveal things to be what they are. We hear this in St. Basil’s Liturgy when we ask God to “show” the bread and wine to be the Body and Blood of Christ. The Baptismal liturgy does the same, asking God to “show this water…to be the water of redemption, the water of sanctification, the purification of flesh and spirit, etc.” This is a very different form of thought. Of course, the language of “making” is also present, but I suspect the “making” is something other than what we often imagine.

In an odd way, when we imagine the world to be “secular,” and fear its progressive banishment of all things religious, we unwittingly agree to be secularists ourselves. The fundamental concept of secularism is that the world, or certain aspects of it, exists apart from God and is entirely self-referential. This tree is just a tree. That sky is just a sky. This imaginary construct is reinforced by labeling certain things as “religious” and placing them in their own zone of influence, as though their removal somehow protects the neutrality of the otherwise secular world.

In point of fact – there is no such thing as “secular.” All things are created by God, and exist only because they are sustained by His good will. Everything points towards God and participates in God who is the “Only Truly Existing One.” When the Orthodox speak of the world as a “sacrament,” it is simply stating this fact.

When God became man, in the Incarnation of Jesus Christ, He shows the sacramentality of all things. First, and foremost, He shows what it means that human beings are created in the image and likeness of God – “He is the image of the invisible God” (Col. 1:15). In a world that appears chaotic, it is shown that the “winds and the sea” obey Him. In His hands, the bread of this world is shown to be the bread of heaven. The seemingly almighty power of the Roman Empire is shown to be only a power “given from above” (Jn 19:11). Even the most brutal instrument of torture is shown to be the Tree of Life.

The concept of “secular” is the direct refusal to acknowledge any of this to be true. It imagines that “religion” is in the mind of the believer and nowhere else. Of course, the very concept of “religion” is something of a secular invention – a name we now use not to describe something, but to isolate something. In this sense, it is correct to say there is no such thing as “religion.” There is life lived in communion with God – whether it is acknowledged or not. When our life in communion with God is unacknowledged, we are living in a delusional manner, pretending that there can be something that is not in communion with God.

Our secularized concept of the world is also a fragmentation of our lives. Our modern economy and politics tends to divide the world into spheres of “influence” or “specialization.” We compartmentalize our lives into a patchwork of loyalties, responsibilities and affiliations. We worry about “balance,” precisely because the patchwork pulls on us in uneven ways. The Latin world for whole is “integer.” Our secularized lives lack integrity. It is brutal for the soul.

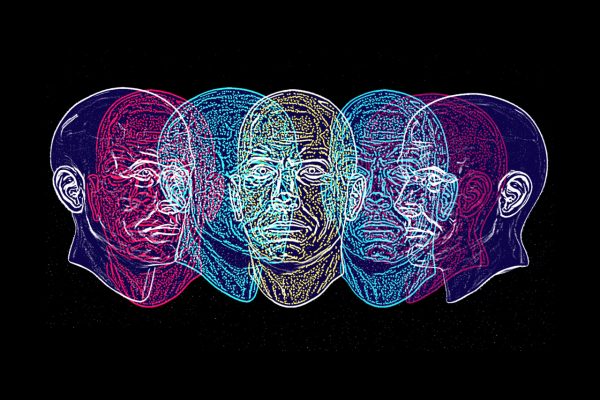

St. James warns about a “double-minded” person (literally, a “two-souled” person), saying that such a person is “unstable in all his ways” (James 1:8). In our culture, we often live a “multi-souled” existence, scattered across the board of competing interests. Various things vie for our attention, such that the very act of seeing something has become commodified. “How many looks did it get?”

The greatest commandment, according to Christ, is to “love God, with all your heart, mind, and soul.” This is not at all the same thing as saying, “Make God first in your life.” God is first only in the sense that there is no second: all means all. This is the only path towards true integrity. St. Paul says it in this way:

“…whatever you do, in word or deed, do everything in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him.” (Col 3:17)

This is not a commandment for our “religious” life, for there is only one life. That one life is our soul.

The compartmentalization of modern life creates false distinctions. There is only one God and one set of commandments for all of life. There is no such thing as “political ethics,” “business ethics,” “medical ethics,” etc. Frequently these distinctions do little more than create specialized islands of interest in which people agree to act in an immoral manner under the guise of their fragmented loyalties.

When Pontius Pilate faced Christ, a moment of judgment was placed before his soul. We see him struggle, pushing the decision away to Herod, to the Sanhedrin, to the crowd. But the decision was his alone. Though he found “no fault” in Jesus, he sent him to his crucifixion. It was “allowed” from above (from God) but not commanded. His wife had warned him to “have nothing to do with that righteous man” (Matt. 27:19).

To Pilate’s credit, an agony of soul was present (he sought to release Jesus). He failed the test and sought to wash his hands (literally) of his inner conflict. Today, our compartments are often so secure that we give little thought to the conflicts between our “religion compartment” and the other realms of our life. I frequently encounter economic explanations that run quite contrary to the gospel but stand “on their own merit” (in their own economic compartment). The same can be said of politics and much else. The secular habit of the heart is to believe that, when all is said and done, we have to make things turn out in accordance with our own wishes or see them turn out according to someone else’s. We imagine the power and the responsibility to be in our own hands.

The salvation of our soul is also a journey towards integrity – becoming wholly and completely what God has created us to be. Theosis cannot be compartmentalized. My experience with this has been that such integrity is best acquired by becoming “small.” The commandments of Christ tend to be quite specific and immediately at hand. He offers no theories for running an empire or managing an economy. When a beggar asks for money, for example, we tend to immediately become “double-minded.” We want to give (the commandment), but we wonder if we’re actually doing harm, or whether he’s being honest, etc. Our hearts become unstable.

To continue with this example, it is possible to give with integrity when we refuse to put ourselves in the place of managing outcomes. This is not done as an act of frustration or indifference. Rather, it is an act of obedience and faith. We do what we are commanded, and trust that God will be God (outcomes are in His hand).

Learning to live as the servant of Christ, rather than the master of humanity, is the beginning of integrity. To gain our souls we must lose the whole world. Strangely, in the mystery of the Kingdom of God, when we gain our souls, we also gain the whole world as well – in simplicity and truth. Then things will be revealed to be what they are and God will be “all in all.”