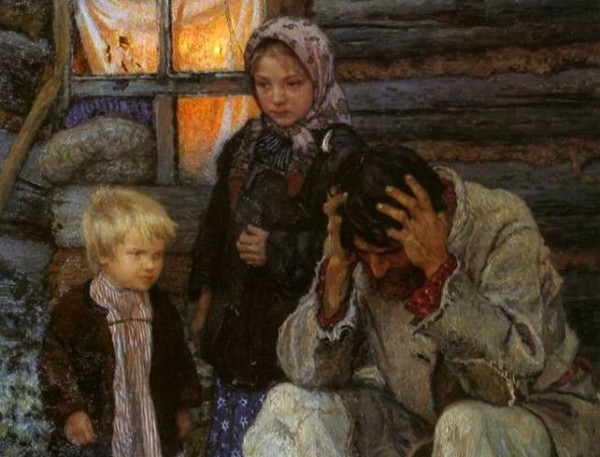

The recent massive deaths that have taken place in the horrible fires that have engulfed California has brought together whole communities in need of mourning. During times like this, we need to mourn.

One of the most rewarding and challenging aspects of the priesthood is comforting people in their darkest moments of sorrow. Do not be mistaken, and think that priests are exempt from the pain of those whom they try to comfort, or that we have magical words that somehow ease the pain or bring order to the chaos of grief. Platitudes are useless in dark days of mourning. The one who has lost his life may very well be “in a better place,” but it is oddly of little comfort to say those words. In a powerful witness of human behavior, Christ “does not say, ‘Well, now he is in heaven, everything is well; he is separated from this difficult and tormented life.’ Christ does not say all those things we do in our pathetic and uncomforting attempts to console. In fact he says nothing—he weeps.”

In like fashion, we need to embrace the grief we feel following at the senseless loss of lives. We need to honor the bereavement process, because just as God gave life to people whom we grew to love, so too God has blessed those left behind with the grief that they feel at their loss. Grief is confirmation that these persons were of value, that they were a beloved son, a cherished brother, a treasured friend. Grief is how we honor a well-lived life. Their deaths were grief-worthy. In grieving, we do their memory justice, and follow in the example of Jesus, who wept at the grave of his friend Lazarus. Like martyrs of the ancient church, like Lazarus in the New Testament, their departure from this world before their time was up makes their deaths particularly galling for those left behind to wonder how they are going to the fill the space that their loved ones once occupied. The mystery of a future without them is a daunting, as is the mystery of death itself.

As a priest and monk of the Russian Orthodox Church, I am comfortable with this mystery, as all Christians should be. Death can be a mystery precisely because the triumph over death is not a mystery. As the Russian Orthodox theologian Alexander Schmemann wrote, “in essence, Christianity is not concerned with coming to terms with death, but rather with the victory over it.” In the light of everlasting life, in the name of Jesus Christ, the dreadful threat and dark mystery that is death is transformed into a happy and victorious event for the believer, and “Death is swallowed up in victory.” (1 Cor. 15:54)

So mourning is an ancient ritual, one in which Jesus participated, and those before him. For all of us, all people, death is a common element of humanity, the common trait that we share, and the common enemy of our loved ones. And like grief, victory over death binds people together in a larger, more powerful community, the community that is found in the Christian faith. People accuse Christians of being members of a “death cult,” obsessed with a dying savior and focused on the afterlife to the exclusion of the present; but they are wrong.

Christianity does not deny life, Christianity affirms life. Christianity affirms life even in death, because for Christians, death does not remove the relationship that exists. In death, as in life, our parent, our son, our brother, our friend, is honored and loved. In death, as in life, we love and honor them, and death cannot take them from us. Death may have taken them, but it has also provided those left behind with the opportunity to live with the hope of one day joining them. And a life with hope is a good life.

So for us, the death of our loved ones is the beginning of the true life that also awaits us beyond the grave, if indeed we have begun to live it here. Christ, “the resurrection and the life,” (John 11:25) transformed death. Christ assumed human flesh, Christ was crucified, resurrected, ascended to heaven and waits for us there, and Christ ushers us into new life both now and after our death. Therefore, even as death exposes our frailty and our grief, death does not reveal our finiteness; instead it reveals our infiniteness, our eternity. To this end, the Christian does not ponder the mystery of death in a way that is paralyzing, negative and apathetic, but in a way that is productive, positive and dynamic.

God, to whom you have entrusted your soul, is a good and perfect God. This God will do what is right with your child, what is just with your brother, and what is honorable with your parent or friend. There is no saying, no claim, no scripture that will give us peace in our loss right now or even calm our troubled souls; but we can find comfort and peace in God who is present with us, and in us, and through us, in the intimacy of grief, as we mourn the death of our friends.

With love in Christ,

Abbot Tryphon