To those who see only through distorting “scales” of Western culture, what seems to be deeply valuable is the heroic individual, who carves out his own proud path, and sings, “I did it my way.” Those who withdraw from this world in repentance and prayer are sneered at as self-indulgent “navel-gazers.”

To those who see only through distorting “scales” of Western culture, what seems to be deeply valuable is the heroic individual, who carves out his own proud path, and sings, “I did it my way.” Those who withdraw from this world in repentance and prayer are sneered at as self-indulgent “navel-gazers.”

But others have heard Jesus teach that the first shall be last, and the last shall be first, and that he who seeks to save his life shall lose it. A few of the scales, at least, have fallen from their eyes, and they strive to follow Christ’s call, “Deny yourself, take up your cross, and follow Me!”

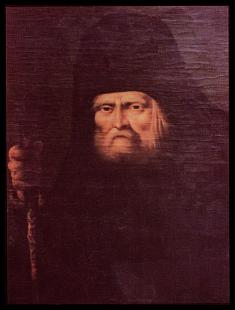

In Archimandrite Lazarus Moore’s biography of the saint, St. Seraphim of Sarov praises the monastic life:

… the saint raised his hands to heaven and with rapture repeated several times in the presence of the Diveyev Sister Paraskeva Ivanovna who was there at the time this doxology to monasticism:

“There is nothing better than the monastic life! Nothing is better!”

(St. Seraphim of Sarov – A Spiritual Biography, Archimandrite Lazarus Moore, New Sarov Press, 1994, p. 255.)

This does not refer to a life of luxury, however, but of ascetic struggle, and one to which we all are called, not only monastics:

To those in Monasteries Father Seraphim advised, in accordance with the general teaching of the Fathers, obedience as a way to humility. And humility is death of the passions. “Renounce your will and receive humility throughout your life. Then you will be saved. Humility and obedience are the eradicators of all the passions and the planters of all the virtues” (Barsanufius the Great, Ans. 309 etc.). “As cloth which the dyer heats, tramples on, combs and washes, becomes white as snow, so a Novice who suffers humiliations, offenses, reproaches, is purified and becomes like pure, shining silver, refined in the fire” (Ant. hom. 113).

And though these words were addressed primarily to Novices, yet in a certain sense the Lord has made the world so that everyone has to submit to someone else, subordinates to their superiors, children to their parents, wives to their husbands, and so on. And everywhere one has to humble and break one’s own will and subject it to the will of others. A mother has to humble herself even with her own children, so as not to be irritated, and not spare a punishment when it is necessary. And what patience, what sufferings are required throughout the education of her children, in their illnesses and the correction of their faults! Sometimes the outward circumstances of life are difficult and painful. Humility and patience are needed everywhere. At other times, the Lord sends us, even in the world, someone to break and crush our pride. Certainly no one in the world is abandoned by the Lord Who cares for the salvation of all; but there is no salvation without humility. And therefore we must watch attentively and ask ourselves: What is the Lord doing this very moment to humble me? And this lesson of God must be at once accepted, without waiting for another, without rejecting it, and without devising one’s own seemingly better ways of salvation. The Lord surely knows best what is best for us, sinners, at a given moment. And what we plan ourselves is usually only the enemy’s red herring to draw us away from the work of God. (Ibid., pp. 319-321.)

St. John Chrysostom also reminds us that even in our busy lives, we, too, are called to the same path, and have the possibility of advancing along it as well:

For even one dwelling in a city may imitate the self-denial of the monks; yea, one who has a wife, and is busied in a household, may pray, and fast, and learn compunction. Since they also, who at the first were instructed by the apostles, though they dwelt in cities, yet showed forth the piety of the occupiers of the deserts: and others again who had to rule over workshops, as Priscilla and Aquila. (St. John Chrysostom, Homilies on Matthew, Homily 55.)

As we all try to walk this path, we look to our monastic brothers and sisters as great athletes of the spiritual struggle, who strive to follow Jesus in crucifying themselves to the world, and the world to themselves. They walk ahead of us. They pray for us all. And they have much to teach us!

The rise and fall of Orthodoxy in different nations in the world often has paralleled the presence and health of monasticism there. The great flowering of in Holy Russia paralleled the rise and spread of monasteries such as that at Optina, and others. These monasteries were able to live and thrive because of the support of the Orthodox faithful, even those far from the monasteries, who understood their value to the Body of Christ, to the world, to themselves, of this prayerful presence, and the teachings from the elders of the monasteries.

Orthodox monasticism has been called, “the barometer of the spiritual life of the Church.” We in America have not grown up with this rich and deep tradition, and many of us are unaware of the small monastic presence in this land, and how precious it is, even when we are unaware of it. We must cherish and support our brothers and sisters, monastic fathers and mothers in the faith who walk, in humility, self-denial, and sacrificial obedience, the prayerfully silent path of the heart.

Again, from the biography of St. Seraphim of Sarov:

Lay people must also honour monasticism in heart and in deed, so as to be able at least in some measure to partake of the grace of monasticism through others. To this end Father Seraphim advised people to give alms to Monasteries or to work for them. (St. Seraphim of Sarov – A Spiritual Biography, Archimandrite Lazarus Moore, New Sarov Press, 1994, p. 261.