To understand the various liturgical particularities of the Lenten period, we must remember that they express and convey to us the spiritual meaning of Lent and are related to the central idea of Lent, to its function in the liturgical life of the Church. It is the idea of repentance. In the teaching of the Orthodox Church however, repentance means much more than a mere enumeration of sins and transgressions to the priest. Confession and absolution are but the result, the fruit, the “climax” of true repentance. And, before this result can be reached, become truly valid and meaningful, one must make a spiritual effort, go through a long period of preparation and purification. Repentance, in the Orthodox acceptance of this word, means a deep, radical reevaluation of our whole life, of all our ideas, judgments, worries, mutual relations, etc. It applies not only to some “bad actions,” but to the whole of life, and is a Christian judgment passed on it, on its basic presuppositions. At every moment of our life, but especially during Lent, the Church invites us to concentrate our attention on the ultimate values and goals, to measure ourselves by the criteria of Christian teaching, to contemplate our existence in its relation to God. This is repentance and it consists therefore, before everything else, in the acquisition of the Spirit of repentance, i.e., of a special state of mind, a special disposition of our conscience and spiritual vision.

The Lenten worship is thus a school of repentance. It teaches us what is repentance and how to acquire the spirit of repentance. It prepares us for and leads us to the spiritual regeneration, without which “absolution” remains meaningless. It is, in short, both teaching about repentance and the way of repentance. And, since there can be no real Christian life without repentance, without this constant “reevaluation” of life, the Lenten worship is an essential part of the liturgical tradition of the Church. The neglect of it, its reduction to a few purely formal obligations and customs, the deformation of its basic rules constitute one of the major deficiencies of our Church life today. The aim of this article is to outline at least the most important structures of Lenten worship, and thus to help Orthodox Christians to recover a more Orthodox idea of Lent.

(1) Sundays of Preparation

Three weeks before Lent proper begins we enter into a period of preparation. It is a constant feature of our tradition of worship that every major liturgical event – Christmas, Easter, Lent, etc., is announced and prepared long in advance. Knowing our lack of concentration, the “worldliness” of our life, the Church calls our attention to the seriousness of the approaching event, invites us to meditate on its various “dimensions”; thus, before we can practice Lent, we are given its basic theology.

Pre-lenten preparation includes four consecutive Sundays preceding Lent.

1. Sunday of the Publican and Pharisee

On the eve of this day, i.e., at the Saturday Vigil Service, the liturgical book of the Lenten season – the Triodion makes its first appearance and texts from it are added to the usual liturgical material of the Resurrection service. They develop the first major theme of the season: that of humility; the Gospel lesson of the day (Lk. 18, 10-14) teaches that humility is the condition of repentance. No one can acquire the spirit of repentance without rejecting the attitude of the Pharisee. Here is a man who is always pleased with himself and thinks that he complies with all the requirements of religion. Yet, he has reduced religion to purely formal rules and measures it by the amount of his financial contribution to the temple. Religion for him is a source of pride and self-satisfaction. The Publican is humble and humility justifies him before God.

(2) Sunday of the Prodigal Son

The Gospel reading of this day (Lk. 15, 11-32) gives the second theme of Lent: that of a return to God. It is not enough to acknowledge sins and to confess them. Repentance remains fruitless without the desire and the decision to change life, to go back to God. The true repentance has as its source the spiritual beauty and purity which man has lost. “…I shall return to the compassionate Father crying with tears, receive me as one of Thy servants.” At Matins of this day to the usual psalms of the Polyeleos “Praise ye the name of the Lord” (Ps. 135), the Psalm 137 is added, “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea we wept, when we remembered Zion… If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning…” The Christian remembers and knows that what he lost: the communion with God, the peace and joy of His Kingdom. He was baptized, introduced into the Body of Christ. Repentance, therefore, is the renewal of baptism, a movement of love, which brings him back to God.

(3) Sunday of the Last Judgment

(Meat Fare)

On Saturday, preceding this Sunday (Meat Fare Saturday) the Typikon prescribes the universal commemoration of all the departed members of the Church. In the Church we all depend on each other, belong to each other, are united by the love of Christ. (Therefore no service in the Church can be “private”.) Our repentance would not be complete without this act of love towards all those, who have preceded us in death, for what is repentance if not also the recovery of the spirit of love, which is the spirit of the Church. Liturgically this commemoration includes Friday Vespers, Matins and Divine Liturgy on Saturday.

The Sunday Gospel (Mt. 25, 31-46) reminds us of the third theme of repentance: preparation for the last judgment. A Christian lives under Christ’s judgment. He will judge us on how seriously we took His presence in the world, His identification with every man, His gift of love. “I was in prison, I was naked…” All our actions, attitudes, judgments and especially relations with other people must be referred to Christ, and to call ourselves “Christians” means that we accept life as service and ministry. The parable of the Last Judgment gives us “terms of reference” for our self-evaluation.

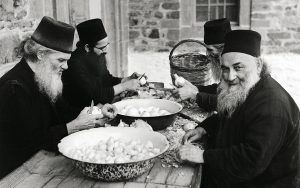

On the week following this Sunday a limited fasting is prescribed. We must prepare and train ourselves for the great effort of Lent. Wednesday and Friday are non-liturgical days with Lenten services (cf. infra). On Saturday of this week (Cheesefare Saturday) the Church commemorates all men and women who were “illumined through fasting” i.e., the Holy Ascetics or Fasters. They are the patterns we must follow, our guides in the difficult “art” of fasting and repentance.

(4) Sunday of Forgiveness

(Cheese Fare)

This is the last day before Lent. Its liturgy develops three themes: (a) the “expulsion of Adam from the Paradise of Bliss.” Man was created for paradise, i.e., for communion with God, for life with Him. He has lost this life and his existence on earth is an exile. Christ has opened to every one the doors of Paradise and the Church guides us to our heavenly fatherland. (b) Our fast must not be hypocritical, a show off. We must “appear not unto men to fast, but unto our Father who is in secret” (cf. Sunday Gospel, Mt. 6, 14-21), and (c) its condition is that we forgive each other as God has forgiven us – “If ye forgive men their trespasses, your Heavenly Father will also forgive you.”

The evening of that day, at Vespers, Lent is inaugurated by the Great Prokimenon: “Turn not away Thy face from Thy servant, for I am in trouble; hear me speedily. Attend to my soul and deliver it.” After the service the rite of forgiveness takes place and the Church begins its pilgrimage towards the glorious day of Easter.

(1) The Canon of St. Andrew of Crete

The Great Canon of St. Andrew of Crete. On the first four days of Lent – Monday through Thursday – the Typikon prescribes the reading at Great Compline (i.e., after Vespers) of the Great Canon of St. Andrew of Crete, divided in four parts. This canon is entirely devoted to repentance and constitutes, so to say, the “inauguration of Lent.” It is repeated in its complete form at Matins on Thursday of the fifth week of Lent.

(2) Weekdays of Lent – The Daily Cycle

Lent consists of six weeks or forty days. It begins on Monday after the Cheese Fare Sunday and ends on Friday evening before Psalm Sunday. The Saturday of Lazarus’ resurrection, the Palm Sunday and the Holy Week form a special liturgical cycle not analyzed in this article. The Lenten weekdays – Monday through Friday – have a liturgical structure very different from that of Saturdays and Sundays. We will deal with these two days in a special paragraph.

The Lenten weekday cycle, although it consists of the same services, as prescribed for the whole year (Vespers, Compline, Midnight, Matins, Hours) has nevertheless some important particularities:

(a) It has its own liturgical book – the Triodion. Throughout the year the changing elements of the daily services – troparia, stichira, canons – are taken from the Octoechos (the book of the week) and the Menaion (the book of the month, giving the office of the Saint of the day). The basic rule of Lent is that the Octoechos is not used on weekdays but replaced by the Triodion, which supplies each day with,

— at Vespers – a set of stichiras (3 for “Lord, I have cried” and 3 for the “Aposticha”) and 2 readings or “parimias” from the Old Testament.

— at Matins – 2 groups of “cathismata” (“Sedalny,” short hymns sung after the reading of the Psalter), a canon of three odes (or “Triodion” which gave its name to the whole book) and 3 stichiras at the “Praises,” i.e., sung at the end of the regular morning psalms 148, 149, 150 – at the Sixth Hour – a “parimia” from the Book of Isaiah.

The commemoration of the Saint of the day (“Menaion”) is not omitted, but combined with the texts of the Triodion. The latter are mainly, if not exclusively penitential in their content. Especially deep and beautiful are the “idiornela” (“Samoglasni”) stichira of each day (1 at Vespers and 1 at Matins). And it is a sad fact that so little of the Triodion has been translated into English.

(b) The use of Psalter is doubled. Normally the Psalter, divided in 20 cathismata is read once every week: (1 cathisma. at Vespers, 2 at Matins). During Lent it is read twice (1 at Vespers, 3 at Matins, 1 at the Hours 3, 6 and 9). This is done of course mainly in monasteries, yet to know that the Church considers the psalms to be an essential “spiritual food” for the Lenten season is important.

(c) The Lenten rubrics put an emphasis on prostrations. They are prescribed at the end of each service with the Lenten prayer of St. Ephrem the Syrian, “O Lord and Master of my life,” and also after each of the special Lenten troparia at Vespers. They express the spirit of repentance as “breaking down” our pride and selfsatisfaction. They also make our body partake of the effort of prayer.

(d) The Spirit of Lent is also expressed in the liturgical music. Special Lenten “tones” or melodies are used for the responses at litanies and the “Alleluias” which replace at Matins the solemn singing of the “God is the Lord and has revealed Himself unto us.”

(e) A characteristic feature of Lenten services is the use of the Old Testament, normally absent from the daily cycle. Three books are read daily throughout Lent: Genesis with Parables at Vespers. Isaiah at the Sixth Hour. Genesis tells us the story of Creation, Fall and the beginnings of the history of salvation. Parables is the book of Wisdom, which leads us to God and to His precepts. Isaiah is the prophet of redemption, salvation and the Messianic Kingdom.

(f) The liturgical vestments to be used on weekdays of Lent are dark, theoretically purple.

The order for the weekday Lenten services is to be found in the Triodion (“Monday of the first week of Lent”). Of special importance are the regulations concerning the singing of the Canon. Lent is the only season of the liturgical year that has preserved the use of the nine biblical odes, which formed the original framework of the Canon.

(3) Non-Liturgical Days

The Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts

On weekdays of Lent (Monday through Friday) the celebration of the Divine Liturgy is strictly forbidden. They are non-liturgical days, with one possible exception – the Feast of Annunciation (then the Liturgy of St. Chrysostom is prescribed after Vespers). The reason for this rule is that the Eucharist is by its very nature a festal celebration, the joyful commemoration of Christ’s Resurrection and presence among His disciples. (For further elaboration of this point cf. my note “Eucharist and Communion” in St. Vladimir’s Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 2, April 1957, pp. 31-33.) But twice a week, on Wednesdays and Fridays, the Church prescribes the celebration after Vespers, i.e., in the evening of the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts (cf. the order of this service in I. Hapgood, The Service Book, pp. 127-146.) It consists of solemn Great Vespers and communion with the Holy Gifts consecrated on the previous Sunday. These days being days of strict fasting (theoretically: complete abstinence) are “crowned” with the partaking of the Bread of Life, the ultimate fulfillment of all our efforts.

One must acknowledge the tragical neglect of these rules in many American parishes. The celebration of the so called “requiem liturgies” on non-liturgical days constitutes a flagrant violation of the universal tradition of Orthodoxy and cannot be justified from either theological or pastoral points of view. They are remnants of “uniatism” in our Church and are in contradiction with both – the Orthodox doctrine of the commemoration of the dead and the Orthodox doctrine of Eucharist and its function in the Church. Everything must be done in order to restore the real liturgical principles of Lent.

(4) Saturdays of Lent

Lenten Saturdays, with the exception of the first – dedicated to the memory of the Holy Martyr Theodore Tyron, and the fifth – the Saturday of the Acathistos, are days of commemoration of the departed. And, instead of multiplying the “private requiem liturgies” on days when they are forbidden, it would be good to restore this practice of one weekly universal commemoration of all Orthodox Christians departed this life, of their integration in the Eucharist, which is always offered “on behalf of all and for all.”

The Acathistos Saturday is the annual commemoration of the deliverance of Constantinople in 620. The “Acathist,” a beautiful hymn to the Mother of God, is sung at Matins.

(5) Sundays of Lent

Each Sunday in Lent, although it keeps its character of the weekly feast of Resurrection, has its specific theme, Triodion is combined with Octoechos.

1st Sunday — “Triumph of Orthodoxy” — commemorates the victory of the Church over the last great heresy – Iconoclasm (842).

2nd Sunday — is dedicated to the memory of St. Gregory Palamas, a great Byzantine theologian, canonized in 1366.

3rd Sunday — “of the Veneration of the Holy Cross”– At Matins the Cross is brought in a solemn procession from the sanctuary and put in the center of the Church where it will remain for the whole week. This ceremony announces the approaching of the Holy Week and the commemoration of Christ’s passion. At the end of each service takes place a special veneration of the Cross.

4th Sunday —St. John the Ladder, one of the greatest Ascetics, who in his “Spiritual Ladder” described the basic principles of Christian spirituality.

5th Sunday — St. Mary of Egypt, the most wonderful example of repentance.

On Saturdays and Sundays – days of Eucharistic celebration – the dark vestments are replaced by light ones, the Lenten melodies are not used, and the prayer of St. Ephrem with prostrations omitted. The order of the services is not of the Lenten type, yet fasting remains a rule and cannot be broken (cf. my article “Fast and Liturgy,” in St. Vladimir’s Quarterly, Vol. III, No. 1, Winter 1959). Each Sunday night, Great Vespers with a special Great Prokimenon is prescribed.

At the conclusion of this brief description of the liturgical structure of Lent, let me emphasize once more that Lenten worship constitutes one of the deepest, the most beautiful and the most essential elements of our Orthodox liturgical tradition. Its restoration in the life of the Church, its understanding by Orthodox Christions, constitute one of the urgent tasks of our time.