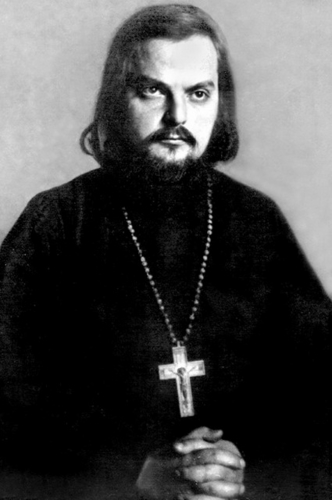

In this urgent and prophetic article, written in 1918 for the Moscow paper Vozrozhdenie (“Rebirth”), Sergius Mechev, who went on to become both a priest and martyr, castigates the Russian intelligentsia for seeking to construct a new social order outside the spiritual traditions of the Orthodox Church.

In this urgent and prophetic article, written in 1918 for the Moscow paper Vozrozhdenie (“Rebirth”), Sergius Mechev, who went on to become both a priest and martyr, castigates the Russian intelligentsia for seeking to construct a new social order outside the spiritual traditions of the Orthodox Church.

“Make peace with yourself, and heaven and earth will make peace with you. Endeavor to enter your own inner cell, and you will see the heavens, because the one and the other are one and the same, and when you enter one you see the two. The ladder leading to the Kingdom is concealed within you, that is, in your soul. Wash yourself from sin and you will see the rungs of the ladder by which you can ascend there.” [1]

When one rereads this page from the works of St. Isaac the Syrian, one is unwittingly struck by the disparity between it and both the modern mindset and the modern conception of life. In St. Isaac the Syrian, everything is directed from the outer shell of the spiritual life towards its eternal and profound root.

For us, in terms of both mindset and practical life, everything that is truly profound and valuable is being exchanged for the petty commonplaces of the reality around us.

Overcome with fervor for life-construction [2], we think we can construct life itself simply by changing its external forms, its external shell, all the while sincerely believing and hoping that its internal structure, which has been formed over many centuries, will somehow be reconstructed along with it.

The lofty ideas of social wellbeing and peace are being brought before our gaze, while at the same time we do not want to take any care to arrange our spiritual life. We want to create a “heavenly cell” on earth, yet we do not “endeavor” to enter our “inner cell.”

Total isolation from our former spiritual-ecclesial experience and complete disregard for the precepts of Orthodoxy are characteristic of our contemporaries. This is true above all with regard to the intelligentsia, which for the course of an entire century has lived solely by its dreams of social wellbeing, inspired by the ideals of service for the good of the people, yet at the same time not displaying any ascetic struggle in its own life and looking altogether condescendingly on its own glaring shortcomings, such as in the family.

It is striking that this divide between the old and new generations, between “fathers and sons,” has nowhere been so palpably and painfully reflected as in our Russian intellectual milieu. No literature has as many types and characters from this area of life as Russian literature.

Is this simply a coincidence or a sign of a specific spiritual illness?

It appears that there cannot be two answers to this question. This divide between the old and new generations, this mutual misunderstanding between Russian “fathers and sons,” has always been a sign of a profound religious infirmity.

This is the other side of the intelligentsia’s consciously cold indifference towards the past experience of the Church, its torturous break with the mind of the Church in mentality and with the life of the Church in behavior, of its shameful flight from its “father’s home” and its wandering in alien countries.

Now that the spiritual schism between the intelligentsia and the people has become so pronounced, what is the Russian intelligentsia doing to overcome the torturous disillusionment to which all of its thought and faith has led it as comes up against life itself?

The great Dostoevsky once said to the Russian intelligentsia: “Humble yourself, proud man, and first of all break down your own pride.” [3] Now one would like to say: “Leave aside your wandering in alien countries, Russian intellectual, and return to the Church, to the ‘father’s house,’ familiarize yourself with the treasure of the Church’s spiritual experience, and learn lessons for your social construction.”

But they will say: should we really learn social construction from the spiritually experienced people of the Church, from the holy ascetic strugglers who severed all ties with society for the sake of their “personal” salvation? Yes, we say, it is this centuries-old experience of the Church that should guide our social life in its basic movement and direction. And, strange as it may seem, we likewise need to learn worldly life from the Christian ascetics who left the “world.”

The shrine of Orthodoxy – which for the course of entire centuries has been hidden from the gaze of the world; and which, like a precious pearl, has glistened and been kept safe in the souls of a few chosen ones of God – must finally be shown to the world, it must regenerate the world. And if there is a genuine social order, it must be that religious social order that has been hidden until the present in the depth of the centuries-old ecclesial experience of Orthodoxy.

And, strange as it may seem again, the genuine social figures in our “worldly” sense were ascetics of Orthodoxy who had renounced the “world.” Living far from the world in the quiet of their cells, they nonetheless lived genuinely social lives, connected by the invisible threads of spiritual communion with all that is pure and lofty in the world while gathering a spiritual flock around them.

It is sufficient to point out the example of our holy ascetic strugglers Sergius of Radonezh and Seraphim of Sarov. Living in the wilderness, they restored the luminous image of God in themselves and in those around them, teaching people to cast off the burden of sin, thereby restoring a new life around them.

Klyuchevsky, the historian of the Russian people, writes that through the efforts of the desert-dwelling St. Sergius, “a harmonious brotherhood was cultivated that left a deeply instructive impression upon the laity… The world looked at the order of life in the monastery of St. Sergius and what it saw – the way of life and atmosphere of the desert brotherhood – taught it the very simple rules by which the community of Christians was strengthened.” The moral influence of St. Sergius’ desert-dwelling “became imprinted on the masses… causing ferment and quietly changing the direction of minds, rebuilding the entire moral structure of the fourteenth-century Russian people’s soul.” [4]

This desert ascetic became a leader, spiritual educator, and social reviver – that is, a social figure in the loftiest and best sense of this word. This religious social order, this sphere in which the great ascetic strugglers of Orthodoxy lived, represents the framework upon which any social order must be built and without which it cannot stand, but will invariably collapse.

This is the social order that springs up from the revelation of the fundamental basis of the human spirit, which is to say, from God’s image in man, which St. Isaac the Syrian invites his spiritual children to recognize.

It is from this point that the construction of our social life should begin. Our intelligentsia, having become detached from the past experience of the Church and having paid for this sin, should come to know its social truth; it should truly experience the spiritual feat of the regeneration of anti-social and sinful man into a genuine social life, one that is spiritual. Only then, having had this experience, should it seek out paths towards our common spiritual regeneration and renewal.

Translator’s notes:

[1] St. Isaac the Syrian, Homily 2.

[2] Zhiznestroitel’stvo (“life-constructing” or “life-building”), which appears to have been popularized by Marxist literary theorist Nikolai Chuzhak (pseud. of N. F. Nasimovich, 1896-1937), was something of a buzzword among the Russian avant-garde.

[3] From Dostoevsky’s celebrated Pushkin speech, given on June 8, 1880, and published in the August 1880 issue of his Diary of a Writer. Dostoevsky is here commenting on lines from Pushkin’s narrative poem “The Gypsies” (II. 510-516).]

[4] V. O. Klyuchevsky, Istoricheskie portrety i etudy. Znachenie prepodobnogo Sergiia dlia russkogo naroda i gosudarstva. [Historical Portraits and Studies. The Significance of the Venerable Sergius for the Russian People and Government.]

Translated from the Russian

You might also like:

Father and Son: A Story of Two Saints

On Controlling the Tongue by St. Sergius Mechev

Let Us Remember Who We Are and What We Are Called To by St. Sergius Mechev