An excerpt from the book “Glory and Honor: Orthodox Christian Resources on Marriage,” edited by David and Mary Ford, St Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Like elementary school students, writers are regularly asked to supply an essay to fit an assigned title. When I learned that the title of this essay would be “The High and Holy Calling of Being a Wife,” I did what any sensible person would do: I tried to get out of it.

Frederica Mathewes-Green

My husband and I celebrated our 40th anniversary last spring, so I have extensive experience in being a wife. But whatever I’ve been doing around here for the last 40 years, “high” and “holy” aren’t terms that immediately spring to mind. For most of us, married life is something we make up as we go along. We learn some deep truths along the way, but usually immediately after it would have been really useful to have known said truth. Whatever height or holiness might have resulted would be entirely the Lord’s doing, not our own.

But that’s true of everything we undertake, isn’t it? We don’t know what we’re doing a lot of the time. We don’t know what’s going to happen next. We don’t know whether what we just did (or said) was the right thing to do (or say). And yet grace still emerges, sometimes at the most unexpected places.

***

My sweetie and I got married May 18, 1974, under a big oak tree. The wedding party, which included a black lab wearing a red bandana around its neck, processed through the clearing, with our hippie friends standing on one side and astonished family members on the other. When we reached the tree, we turned to the gathering and recited the “God is Alive, Magic is Afoot” passage from Leonard Cohen’s novel, Beautiful Losers. (Everyone calls him “Fr. Gregory,” but I still call him by the name he had when we met. In these pages I’ll call him “G.”)

We had asked our friend, an Episcopal priest, to conduct the service, and were disappointed when he told us that we could not write our own vows. So instead we selected the coolest option from that church’s book of experimental services. We were hardly Christians at that point, and could have been better described as all-religions-are-equal syncretists. We considered Christianity less profound than some religions further East, but endearing in its own little way. About halfway through the service I read a Hindu prayer.

My dress was a simple shift of unbleached muslin. Instead of a bouquet, I wore a circle of flowers in my hair. (I meant this to be rebellious, but the joke was on me: crowns are essential to the Orthodox wedding service, and an ancient emblem of marriage.) After the service, the puzzled caterer set out the requested vegetarian reception. And then, as a string quartet played, we joined hands with our hippie friends and danced in circles under the trees.

This seems the place to say “I guess you had to be there,” but you actually didn’t have to be there. You’re picturing it just fine. When archeologists unearth our wedding photos hundreds of years from now, they’ll be able to place the date within five years.

***

Now fast-forward twenty-five years, to the day our youngest went off to college. I had been out of town, and when I got home that night I stood in the kitchen while my husband recounted the highlights of the day. The house seemed strangely empty—perhaps just reverberating silently, after all those years of nonstop music.

G. was talking to me and I was looking at him. I was thinking, That’s it? Just him and me, now, for the rest of our lives?

It’s a cliché for long-marrieds to say “There were ups and downs,” but this is one of those sayings that became a cliché because it’s true. As I looked forward that night, standing in the kitchen and contemplating the years ahead, I’d have said it was one of the “downs.” Children in the home had kept my days full of fun and busy-ness. Suddenly it was just him and me. It didn’t look like it would be enough.

But not long afterwards I ran into an older friend who was enjoying post-retirement travel with his wife. “We’re more in love than ever,” he told me. “These have been the happiest days of our married life.” That gave me something to think about.

So time passed as it usually does, and at some later point I realized that what my friend had said had become true for me, too. At some point in that glacial, imperceptible pace of married life, something had changed, or maybe I changed. Now I can say that we’re more in love than ever, and these are truly the happiest days of our married life.

How that happened I really don’t know. Is there anything I could say in general about the calling of being a wife? I only know about the calling of being a wife in this particular marriage. It seems like any advice that could apply to all wives everywhere would be so vague as to be useless. (Not that there is any lack of advice-giving; I saw an online list that included a recommendation to “Confront and master the inevitable crises of life.” Check!)

Yet people living in our culture today clearly need some help in learning how to make marriage work. Statistics show that 43% of first marriages fail in the first 15 years, while second and later marriages fail 60% of the time.[i] Despite this, most people do little preparing for marriage, harboring an illusion that all that reckless, headstrong early love will hold them together. When things get rocky, they don’t know how to respond. Getting married is about the most far-reaching, life-changing thing most people ever do, but they go into it knowing less than they would if they were planning to buy a ferret.

Why do people get married? How do they stay married? If there is a sanctity to marriage, a holiness in the wife’s and husband’s calling, what is the nature of that holiness? Just how much exalted significance can married life bear, when it has to be conducted by people who are crabby, oblivious, or bored?

I don’t have wisdom adequate to such lofty questions, but over the years I’ve learned some lessons that, I hope, might prove helpful to others:

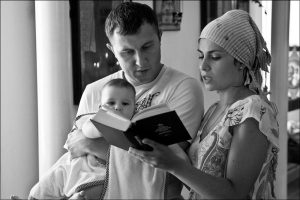

Photo: http://lady.obozrevatel.com/

– Perhaps the first difficulty is that we don’t expect marriage to be difficult. We think, “We’re in love, and that solves everything.” But as long as the two people in love are human, there are going to be misunderstandings, miscommunications, and misplaced expectations. The most pernicious factor in a marriage (or any other relationship, really) is a sneaking suspicion that the other person has more power—that he’s getting his own way too often, and things aren’t fair. You can develop a habit of wary watchfulness, standing guard over your rights and viewing your husband with suspicion. It’s easy to do this, and it’s entirely contrary to our calling in Christ, which is to bear all and embrace humility.

A power struggle is a teeter-totter that never comes to rest. As both partners adapt to it in self-defense, they form a long-term habit of vigilance and mistrust. This makes them unwilling to risk generosity, unwilling to let past “unfairness” go. Nothing good comes of this.

This mutually-assured dysfunction occurs so naturally that preventing it requires deliberate counter-moves. We already know that we’d rather live a different way; we already know that the people we most admire are those who are kind and generous, and that the best love stories are the ones marked by great self-giving. You can start living in such a story any time you want. All you have to do is start practicing generosity, humility, and self-giving.

But, since we’re human and timid and afraid of loss, it helps to make this goal mutual and explicit. One couple I know made a vow on their wedding day to “out-serve” each other. My husband and I evolved a pattern of making decisions based on who feels most strongly about the matter. If I want Chinese food, but hereally wants Italian, we get Italian. If I really want him to watch a Jane Austen movie with me, he does, until he falls asleep 45 minutes later. It doesn’t matter who “won” last time, because a next time is always coming up. The future just keeps rolling into the present, and more good things to give and to receive will always be appearing.

Photo: : livemaster.ru

–Sometimes it is harder to receive than to give, actually. Receiving implies need, and admitting need takes humility. Allow your husband to serve you sometimes. Take notice and be grateful, and say so, out loud.

-Learn this: many regrettable situations can be avoided by keeping your mouth shut.

-A good time to keep your mouth shut is when your husband is telling a story and gets something wrong. If he’s doing anything less serious than teaching brain surgery, resist the urge to interrupt with a correction. If the listener walks away with a misremembered anecdote or a fumbled joke, no lasting harm is done.

This is an example of a larger principle, that of honoring your husband: “Let the wife see that she respects her husband” (Eph 5:33). When you love your husband, you come more and more to be on his side. You want him to succeed. You want people to look up to him. You don’t want people to notice that he’s getting the story wrong; you want to cover his flaws and highlight his gifts. You come, that is, to feel for your husband the kind of fierce loyalty that you feel toward your children.

Married people should praise each other. Praise your husband to other people. Everyone can use a cheering section.

-A corollary is: Don’t complain to others about your husband. Don’t tell stories designed to make him look small or stupid. If your relationship needs help, get help, but don’t be a casual traitor.

– Nobody talks about this, but one of the best things in marriage is the way you can get punchy and silly when you’re both over-tired late at night. That’s when some of the best long- running jokes of the relationship are going to make their debut. Much can be said about the archetypal dignity of the marriage bed, but being silly there is a great joy, too.

-Defenders of traditional marriage often point to procreation as its self-evident purpose, and it’s true that mating holds an irreducibly basic place among human activities. But many things we do have meanings beyond their simple physical effects. The basic purpose of food and drink is to keep the body alive; yet we eat and drink for many other reasons, having a slice of cake at a party, a cup of coffee with a friend. While marriage is the right setting for sex, the sexual union of two people means much more than making babies. As St. Paul says, “This mystery is great, and I am saying that it refers to Christ and the church” (Eph 5:32).

-Here’s something practical I wish I’d known a long time ago. It’s something I learned from an episode of WNYC’s RadioLab [ii]. In it, neurobiologist Robert Sapolsky explained that our bodies go through swift, predictable changes when we get angry: muscles tighten, heart beats faster, and adrenalin starts to surge.

When the argument is resolved, men’s bodies quickly go back to baseline normal. But not women’s bodies. Her body keeps telling her “You’re really angry!,” even when the argument is over.

In trying to figure out why she still feels angry, a wife may cast about, looking for a reason. She might land on an entirely different topic to argue about. The husband suddenly finds himself re-accused of past events that he thought had been resolved.

A woman can’t force her body to return to physiological equilibrium, but she can decide, in the interim, to stop arguing and go do something else. Sapolsky said that he and his wife have found it useful, in the throes of an argument, to say “Honey, don’t forget what the half-life is on the autonomic nervous system.”

– Here follows a way to put that information to practical effect. Go ahead and go to bed angry. Those lingering late-night arguments are the worst; you’re exhausted, bleary, and miserable, and you’re not making any sense. Just stop talking. Turn out the light. Sleep is truly a blessing, and things actually do look better in the morning.

-One of the most difficult tasks in marriage is forgiveness. My husband has been a pastor for nearly 40 years, and we’ve seen many a marriage struggle back from a severe violation of trust. It’s not easy, but it’s possible; and since love is the essence of marriage, recovery should be the goal.

One reason people find forgiveness difficult is that they don’t know what it is. (I’m thinking now of forgiveness in general, and not only in marriage.) Some think it means pretending that the hurtful deed never happened, or that it was excusable, or wasn’t really wrong. On the contrary, the very premise of forgiveness is that real damage was done. That’s the basis on which God forgives us. Forgiveness does not preclude justice; it might still be necessary for that person to pay for his wrong, even though you have forgiven him.

So forgiveness is not denial or overlooking a wrong. It simply means making a decision to move on—a decision to stop cultivating anger and cherishing revenge. As they say, staying angry is like drinking poison and waiting for the other person to die. Even when the other person is unrepentant, the injured person can decide to forgive for the sake of her own soul’s health.

Forgiving the past does not obligate you to trust the person in the future. In some situations, you may need to break off the relationship entirely. That would be the usual course in a low-commitment situation, for example, if a person you’d hired for some home repairs failed to do what he promised. But in marriage a lot more is at stake. It’s possible to make a new start in the ashes of disappointment; some marriages come back even stronger, when pain and humiliation have opened a way to deeper honesty. There will be plenty of reasons over the years to ask forgiveness, and to give it, in every marriage.

-Always remember that marriage does not exist in theory. It exists only in specific real-life manifestations, an ongoing improvised project conducted by two fallible people. Our ideas about marriage (or Marriage) are encumbered by so many preconceptions that at-home reality can suffer in comparison. We may think something is going wrong if marriage doesn’t fit our expectations, but it might be merely that this is what this particular marriage is going to be like. One partner’s pre-set notions of what a theoretical Husband or Wife should be like can hurt the real-life spouse in untold ways, even to the point that he or she gives up.

As an early-seventies feminist, my image of what a marriage was, or what a husband was, was pretty dour. It was a surprise to find out that real marriage was something else entirely. It turned out that I didn’t have to be married to “a husband;” instead, I would be married to G.—my love, my hero, my fun and funny best friend. I felt like I had cheated the “oppressive” expectations of society; I had married G. instead of a husband.

Photo: p-beseda.ru

– The purpose of every life is union with God. Those we journey with—in friendships, families, and particularly in marriage—are put there to help us on our way. A husband and wife, knowing each other’s faults and struggles, can make up what is lacking, and learn from each other’s strengths. Accountability shores up resolve. Unity is a bulwark. “And though a man might prevail against one who is alone, two will withstand him. A threefold cord is not quickly broken.” (Eccl 4:12).

The common center of their love gives each partner greater stores of stability, security, and generosity, resources that flow from them out to the world. We can see a parallel example in the pairs of saints who worked together in this life, like the physician-healers Zenaida and Philonella, the “roving reporters” Sophronius and John Moschus, and the spiritual fathers Barsanuphius and John. They felt for each other love of a familial or friendly kind, and married love is of a different order; yet, like them, married couples can find that sharing great love with another person in no way limits your ability to care for others. In fact, having the support of another person enables more love for others, giving twice the resources to draw on, twice the strength, insight, and compassion.

When spouses are praying for each other, encouraging each other, they spur their mates to greater heights. “Let the husband hear of these things [the ways of virtue] from the wife, and the wife from the husband,” said St. John Chrysostom. “Let there be a kind of rivalry among all, in endeavoring to gain precedence.”[iii]

-The older I get, the more clearly I see that I need my husband. The last decades of life are unpredictable, and potentially tragic. It doesn’t stop being tragic just because tragedy is so likely. I heard that the wife in an elderly couple I know was losing her mind to dementia, and was sad to hear it, but accepted the news in the usual way; it’s just one of the unfortunate things that can happen when you’re old. But if you imagine that it was a couple in their twenties, and heard the wife had begun gradually and irreversibly losing her mind, you wouldn’t just say, “Ah, what a shame.” It would be horrifying. Well, it’s just as horrifying to lose your beloved at the age of 70 or 80. The fact that everyone is treating it as “just one of those things” would only make you feel more alone.

Old age is surprisingly hard. My husband had had, from the time we met, a sentimental expectation that our golden years would be restful and content; but as we march through our 60s we’re discovering that everything hurts. And nobody prepares you for this. When you’re a teenager, people are always shoving booklets into your hands with titles like “Your Body is Changing.” When you’re old your body once again goes through dramatic changes, but nobody warns you ahead of time. Old, reliable parts start unexpectedly failing. It seemed there was a wry joke hidden inside the saying, “Two become one.” We used to be two whole people, but now we have only one functioning pair of knees, one reliable pair of ears, one pain-free right thumb. We’re being gradually whittled down from two to one.

It does no good to go to a doctor expecting healing; you’re more likely to encounter a shrug. I went to a neurologist to find out why, after a lifetime of being a great speller, I was now forgetting how to spell even some simple words. He told me that this was perfectly normal: by the age of 60 we have lost 25% of our brain cells.

How can that kind of loss be “normal”? It’s not normal for me. In my experience, “normal” means enjoying use of 100% of my brain cells. It is normal only if you mean that what happens to my brain doesn’t matter, because I am last year’s model and being phased out anyway.

These losses would be hard to bear at any time of life, and being old and weak and facing multiple losses at one time doesn’t make it any easier. This is when you really need a good marriage. You need someone who will be on your side, who will care about you and fight for you, as you become weaker and less able to do everything for yourself. You might wind up with dementia. You might be incontinent. People hired to give care in such cases are not well-paid. Few go into that line of work because they love old people. (Not all old people are loveable; some are angry or verbally abusive. That could be you, too.) When you are old and helpless, you are only as safe as the amount of love inside the person beside you.

Are you saving up for retirement? Save up for this impoverishment every day. It might turn out to be a hard job, being with you in your old age. If you pour yourself out in love for the other every day, you make the best possible investment against that time.

Photo: http://lady.obozrevatel.com/

***

The calling of being a wife is high and holy because it is eternal. Look at the things in the room around you right now: everything you see is temporary. The only thing that last forever is people. Each of them is an eternal being, called and destined to blaze up with the glory of God. Wives and husbands are especially called to tend each other as they walk the way of the Cross, the way of transformation, a way that never ends.

When St. John Chrysostom comforted a young widow, he reminded her that she would be with her husband for eternity, not in his earthly beauty but in radiance of an eternal and unimaginable kind. “You shall depart one day to join the same company with him, not for twenty or one hundred years, nor for a thousand or twice that number but for infinite and endless ages. …[T]hen you will receive him back again no longer in that corporeal beauty which he had when he departed, but in luster of another kind, and splendor outshining the rays of the sun.”[iv] This is our destiny, as wives; let us spend our humble, earthly lives in the sort of love that prepares us for such glory.

_____________________

[i] Statistics show that National Stepfamily Resource Center. “Stepfamily Fact Sheet”. Retrieved April 24, 2014.