(Part II of II)

The following is translated from a talk given by His Grace, Atanasije (Jevtic), Retired Bishop of Zahumlje and Herzegovina (Serbian Orthodox Church), at the Sretensky Seminary in Moscow on November 1, 2001.

There is a Greek iconographer named Fr. Stamatis Skliris who studied medicine and then theology, became a priest, was an artist for a short time, and then became an iconographer; he has had exhibitions in Paris. He visited us recently. He is a good iconographer, one of the best in my opinion; even in theory he has surpassed [Leonid] Uspensky, who was a good theologian and artist in Paris. He is a slikar, a painter, what the French call une peinture. He is a critic of Western icons and paintings. (It is said that when Picasso learned that one of his paintings at an exhibition had received the top prize, he replied: “But you’ve turned it upside down…”)

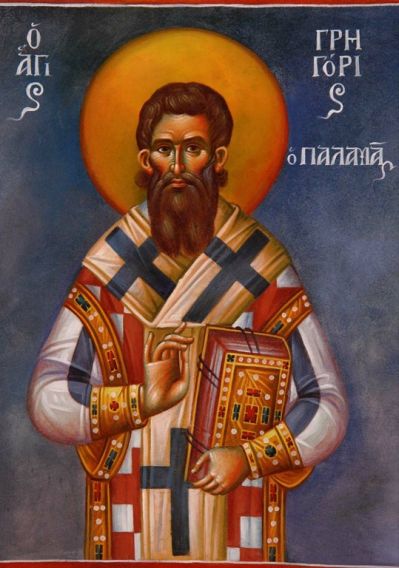

Fr. Stamatis says that the Orthodox icon is light-created while the Western icon is shadow-created. And indeed, Western pictures – even icons and frescoes – ever since the Middle Ages have had shadows everywhere. Whereas with us, we start with dark colors – and then light, light, light! This was the case even before hesychasm, of course, but hesychasm confirmed it. This means that the difference [between Eastern and Western icons] is not just that of reverse perspective, but also that our icons are woven from color and are light-structured, while those of the West are shadow-structured. This is indeed the case. It would be a good idea to translate Fr. Stamatis. [1]

This means that everything is woven and filled with light: this light is Divine grace, God’s love, Divine energy – and this is what the Apostles saw. What is also important is that one can see this light even with one’s bodily eyes, albeit partially. Palamas cited this from the troparion: “When Thou wast transfigured on the mountain, O Christ our God, Thou didst show Thy glory to Thy disciples as far as they could bear it” – that is, as far as they could see it. But their eyes were also transfigured from within, so they could receive the Divine light.

Barlaam reasoned like a rationalist, like a humanist of the period of the Western Enlightenment. Maxim Gorky said: “Study, children, day and night; knowledge is light, knowledge is might” (this is what we were taught; it is some sort of play). That is, light is knowledge – it “enlightens.” Makriyannis, a Greek commander who led the uprising, put it differently. When the Germans arrived, supposedly to bringing enlightenment to the backward and conservative Greeks, he said: “The light you have brought blinds us. We have our own light, an internal one.” These were the words of Makriyannis, a simple man, but a hero. [2]

Of course, the same thing happened with us Serbs. Enlightenment is always superficial. Barlaam said that this is the light of the mind. There was some kind of enlightenment, some kind of inspiration – but it was all created.

Now new ideas and new horizons have opened up to us. People say: global education, global enlightenment! But for us, as Fr. Justin [Popovich] put it, enlightenment comes from holiness. The saints are the true enlighteners. We speak of St. Gregory of Armenia, St. Nina of Georgia, Sts. Vladimir and Olga, Sts. Cyril and Methodius as our enlighteners. With what did they enlighten us? With the Gospel and the knowledge of God. This means that it is the true knowledge of God and the Holy Gospel that enlighten us. Such enlightenment is much better because it is eternal, uncreated, and Divine – unlike this “worldly enlightenment.”

Of course, secular knowledge is good, too. Fathers such as Basil and Gregory first studied in secular schools – just as Palamas later studied in Constantinople –and then went on to the Divine school. That is, this light is also good, but it is not essential – even if it can be useful. St. Gregory the Theologian said: “It is foolish to fight against knowledge.” Only foolish people want everyone to be like them, saying that one does not need to study. Sometimes one hears the same thing among monks: that one does not need to study in school, that one can become holy and enlightened without such study. But the one is not opposed to the other; what is important is which is given priority.

This is the realism of the Orthodox experience, which is shown by the theology that has disclosed and justified it. This has always been the case in the history of the Church, as Fr. Georges Florovsky said: theology discloses and justifies that by which the Church already lives and which it already possesses. Nothing new has been invented in our faith; it is the Pope who is always coming up new dogmas, resulting in great difficulties.

If the Mother of God was conceived immaculately, then there is no sin – so then why did She die? The Pope, who affirmed the dogma [of the Immaculate Conception] in the nineteenth century, afterwards spoke of Her ascension, of Her assumption into heaven, without mentioning death: instead of “She died,” he said: “the Lord took Her to Himself in heaven.” But we believe that She died and that after a certain time the Lord took Her to Himself before the [general] resurrection. But inasmuch as I understand the Fathers, she, too, will be fully resurrected at the general resurrection. She is with the Lord: this is the mystery of the Mother of God, a sort of foretaste of the Kingdom and Resurrection.

Just as, for instance, although the Lord had not yet undergone the Passion at the time of the Mystical Supper, He shed His Blood and gave Communion to the Apostles – which was a real Communion, a foretaste, a pre-suffering. In Communion we partake both of the suffering Lord and the Risen Lord, since these coincide. But He offered the Mystical Supper before His suffering: “Take, eat: this is My Body, which is broken for you” – but it had not yet been broken. Gregory of Nyssa says that the Lord wanted to demonstrate that He was going voluntarily, and not because of the malice of the Jews or the judgment of the Romans. And when Peter tried to turn Him aside, in Matthew 16 – the same ardent Peter who had said: Thou art Christ, the Son of the living God – the Lord replied: Get thee behind Me, Satan (Matthew 16:23). The Pope should know that the Lord said this to Peter even after his confession. Moreover, Peter later denied the Lord and had to be restored to his apostolic dignity by threefold repentance. The Pope did not speak of himself in this way.

There was a Greek, Photios Kontoglou, a good writer from Asia Minor who became a refugee in Greece and a fine iconographer, who wrote an article in which he said: “Why did the Pope choose the Apostle Peter as the patron for his infallibility? If he had spoken of some Apostle who might not have sinned, then this might still have made some sense. But Peter made 300 mistakes” (nkafes refers to when a child is making mischief). Of course, the Lord chose Peter as His foremost disciple, but always as equal to the others, since Peter was a human being, understood human weaknesses, and was indulgent to others. If He had chosen an angel, St. John Chrysostom says, the angel would not have understood someone who sinned once, twice, three times, seven times, seventy-seven times. The angel would have had enough!

In is recorded that the following marvelous event took place on the Holy Mountain of Athos in the sixteenth century. There was a sinful man, a poor thing, who had a weakness of the body; he renounced it many times, beseeching God that he would not sin. He went to church, wept, made promises to the Savior, and then left – and once again sinned, and once again returned. This went on for a long time. Once, many years later, he came and wept before the Lord, repenting: “O Lord, help me; I will stop!” Suddenly the devil could stand it no longer, and said to Christ from the porch of the church: “That’s how You are; You don’t understand a thing! This one swears and weeps to You while he’s here, but as soon as he leaves he’s mine and will do whatever I want. Why do You put up with him?” Then the Lord answered from the icon: “Why do you come to him when he is Mine? I do not bother you when he is yours. I accept a man in the condition in which I find him.” And at that very moment this man died.

This is how the Lord took him. Such is the Lord’s patience!

The reality of salvation is deification and communion with God. It is real, and not intellectual, emotional, or sentimental. Palamas has the courage to say that when man unites with God through deification he does not disappear, but is glorified; the Lord fills him with grace and renews His bond with him. When Barlaam said that man’s ascetic struggle should be for the acquisition of dispassion (apatheia, passionlessness), that one needs to kill all one’s desires to become calm and dispassionate, Palmas replied: “But that is a corpse!”

The Stoics also said that one needs to attain apatheia, to put to death all one’s feelings and movements. The Buddha said the same thing: that the principal evil is the thirst for life, and that this needs to be renounced. Not just thirst for physical or spiritual pleasure – no, life is evil, it needs to be renounced! This is terrible! Fr. Justin said that Buddhism is the maturity of despair.

Palamas said to Barlaam (not, of course, referencing the Buddha) that our ascetic struggle is not to reach apathy, not to kill everything, but rather to offer a “living sacrifice” to God in all things. The cleansing and subduing of the passionate capacities of the soul and body is essential. One needs to turn them towards God: God gives us these capacities for us to live by means of them. One needs to offer a living sacrifice pulsating with eternal life.

Here is a commentary. When I read the following, I saw why Orthodoxy is always joyful. Many say that one needs to mortify oneself, become “dead” – but this is hardly possible to do. It is impossible when grace is present, for grace gives life. Ignatius of Antioch is going to his martyrdom – he is already an old man, nearly eighty – and says: “I hear the sound of living water; I hear a gurgling brook that says: ‘Come to the Father.’” [3] And this is an old man of eighty! This is what Orthodoxy is.

Ascetic struggle consists not of mortification, but of purification from mortality. Sin is mortality and perishability. As the Apostle Paul put it at the beginning of his apostolic labors, we need to turn from dead works to the living God (cf. Hebrews 9:14; 6:1).

Saul could not have become a Christian, could not have become the Apostle Paul, until Saul had died. When Saul died and rose in Christ as Paul, everything that had been good in Saul was given enormous potential; it blossomed and realized its full significance.

Palamas put it this way: the deified man becomes infinite, eternal, immortal, and even – and here he is repeating Maximus – beginningless! There is a paradox for you! Man’s existence has a beginning, but it does not have an end, like a geometric ray that begins at one point and goes on infinitely. But Palamas says that one can also become beginningless – how is that possible? He simply enters the eternal course of the Divine life: that circling, inclusion, or perichoresis, that is the mutual indwelling of Divine life. Therefore one becomes encompassed within this life, is nourished by this life, and lives in this life, which is beginningless. In this sense, deification is the grace that one receives, as the Apostle Paul said: I live; yet not I, but Christ liveth in me (Galatians 2:20).

Palamas is a theologian who reinterpreted all of Holy Scripture, as our Metropolitan Amfilohije said in his fine study of Palamas’ triadology [4]; it is a renewed interpretation of Holy Scripture. He neither changed nor rejected anything; he truly had such a gift from God.

This all happened before the great suffering of the Orthodox that took place five centuries later, and therefore we survived in part thanks to hesychasm. I believe, as St. John of Kronstadt and others have said, that the Russian Church survived its terrible suffering thanks to the blood of the martyrs. God will not leave us; He will give new holy people in the future as well – one only needs to believe in God and in the Church. Yesterday we called to mind Tyutchev: “Russia cannot be understood by the mind… one can only believe in Russia.” [5] So, one must believe in Holy Russia and in Orthodoxy!

Translator’s notes:

[1] An album of his iconographic and artistic work, along with a number of his essays, exists in English: In the Mirror (Sebastian Press, 2007).

[2] Yannis Makriyannis (1797-1864) was a hero of the Greek struggle for independence, achieving the rank of general. Today he is best known for his Memoirs, a monument of Modern Greek literature written in pure Demotic Greek.

[3] Cf. Letter to the Romans, 7:2.

[4] Tajna Svete Trojice po ucenju Grigorija Palame, 1973.

[5] From a four-line poem (now become proverbial) written by the great Romantic poet Fyodor Ivanovich Tyutchev (1803-1873) on November 28, 1866.