This article comes to mind as we celebrate the Liturgy of the Pre-Sanctified Gifts on these Lenten Wednesdays and Fridays. There is nothing to compare to them in the Christian liturgical world. It’s hard to think of fasting in the midst of such a feast.

Orthodoxy has a number of “favorite” words – all of which fall outside the bounds of normal speech. Though we commonly use the word “mystery” (for example), popular speech never uses it in the manner of the Church. I cannot remember using the word “fullness,” or even “fulfilled,” in normal speech. More contemporary words have come to replace these expressions. This doesn’t mean that an English speaker has no idea of what the words mean – but, again, they do not understand these words in the manner of the Church. There is a reality to which words such as mystery and fullness refer – a reality that carries the very heart of the Orthodox understanding of the world and its relation to God.

In popular usage, the word mystery has become synonymous with puzzle. Thus a mystery is something we do not know, but something that, with careful investigation is likely to be revealed. In the Church, mystery is something which by its very nature is unknown, and can only be known in a manner unlike anything else.

Words such as fullness and fulfilled are equally important and specialized in the language of the Church, but whose meanings bear little resemblance to popular speech. Fullness (pleroma), occurs a number of times in the New Testament. It was also a favorite word in the writings of the gnostics. In Christian usage it refers to a spiritual wholeness or completeness that is being manifested or revealed in some way. It is more than a Divine act – it carries with it something of the Divine itself. It is not simply the action of God, but is itself God. Prior actions and words may have hinted at the fullness, but in the revelation of the fullness all hints will have passed away and been replaced by the fulness itself.

The core understanding of words such as mystery and fullness is the belief that our world has a relationship beyond itself, or beyond what seems obvious. The world is symbol, icon and sacrament. Mystery and fullness reference the reality carried as symbol, icon and sacrament.

Many people read the frequent statement in the gospels: “This was done so that the prophecy of Isaiah (or one of the other prophets) might be fulfilled….” What many people think this means is that the prophet made a prediction and it came true. Biblical prophecy (in a proper Christian understanding) has little to nothing to do with prediction. The prophets do not see the future – they see the fullness. What comes to pass is the fullness breaking into our world such that the prophecy “has been fulfilled.”

This same fulness is referenced in Ephesians:

And He [the Father] put all things under His [Christ’s] feet, and gave Him to be head over all things to the church, which is His body, the fullness of Him who fills all in all (1:22-23).

This description of the Church as the “fullness,” is among the most startling statements in Scripture. The phrase, “the fullness of Him that filleth all in all,” is an early version of “God became man so that man might become god” (St. Athanasius, 4th century). God is the one who fills, and we are what is filled (or even the “filling”). At least as striking is a kindred passage in Colossians (the two letters have many similarities):

For in Him dwells all the fullness of the Godhead bodily; and you are complete in Him, who is the head of all principality and power (2:9-10).

The English disguises the wordplay within the verse. We are told that “in Christ dwells all the fullness (pleroma) of the Godhead (or deity) bodily, and you are the ones who have been made full (pepleromenoi) in Him…” Again, this time Christ is described as the fullness, but we have also been made the fullness (pleroma) in Him. His life is our life, and this life or fullness is precisely that which is important about us.

The idea is not dissimilar to Christ’s statements in St. John’s gospel:

I do not pray for these alone, but also for those who will believe in Me through their word; that they all may be one, as You, Father, are in Me, and I in You; that they also may be one in Us, that the world may believe that You sent Me. And the glory which You gave Me I have given them, that they may be one just as We are one: I in them, and You in Me; that they may be made perfect in one, and that the world may know that You have sent Me, and have loved them as You have loved Me (17:20-23).

In John, Christ has given us “his glory,” just as the Father gave Him glory. Glory is not praise or reputation, but rather something substantial (as I search for words). In Hebrew, glory (Kavod) is precisely something substantial, the weight of something. God’s kavod pushes the priests to the ground at the consecration of Solomon’s temple (1 Kings 8:11). But glory is not simply an effect of God, it is, somehow, God’s presence itself.

Fullness has a relation to glory, in this substantial sense.

… we beheld His glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father, full [pleres] of grace and truth…. And of His fullness [pleroma] we have all received, and grace for grace (Jn. 1:14 and 16).

The glory of the only begotten is full of grace and truth and it is of this fullness that we have all received.

I am sure that this excursion through Scripture may be somewhat tedious for readers – but it is an excursion through unknown territory for many. Mystery, fullness, glory and the like are largely neglected in many of the doctrinal structures of the West. Where they are not neglected they are stripped of mystical content and morphed into more rational systems.

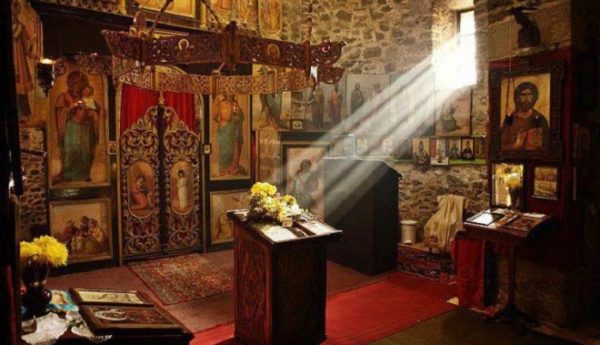

Within the Orthodox East, the mystical content is allowed to shine forth – particularly within the liturgical life and prayers of the Church (this is also true of the ascetical tradition of the Church). One place where language and reality are deeply united is in the Liturgy of the Pre-Sanctified Gifts (celebrated on the weekdays of Great Lent and Holy Week). The Eucharist is not celebrated on these days, but communion is given from the gifts consecrated on the Sunday previous – thus the “Liturgy of the Pre-Sanctified Gifts.”

It is a very solemn service, with a liturgical “climax” when the Pre-Sanctified Gifts are brought out of the Altar and processed through the congregation in silence. The congregation is prostrate during this procession with faces to the floor. Thus the procession occurs in silence and “invisibly.”

Just before the entrance, the choir sings, “Now the powers of heaven do serve invisibly with us. Lo, the King of glory enters. Lo, the mystical sacrifice is upborne, fulfilled.” The Gifts of Christ’s Body and Blood are indeed the “mystical sacrifice,” the very mystery hidden from the ages made manifest and present in the midst of the Church. This same mystery is also the fullness – its presence is fulfilled.

The Christian life lived within the mystery is a life in which God is hidden, made known, revealed, perceived. It is a life in which the Kingdom of God is breaking forth, not destroying nature but fulfilling it. In the same manner, we are not destroyed by our union with Christ but rather fulfilled. We become what we were created to be – the fullness of that life and more is made manifest within our own lives.

It is this same fullness that describes the lives of saints. Saints are more than moral exemplars to be copied – they have the quality of life-fulfilled. In them the fullness that is ours in Christ is made manifest.

The mystical life marks the whole of Orthodox Christianity. It’s doctrines are replete with references to the mystery and speak of matters such as the atonement in a manner that is consistent with the revelation of this mystery. The Conciliar definitions, from first to last, are rooted in this language and presuppose its grammar within every aspect of the life of the Church.

Upborne, fulfilled.