Continued from part one.

Iconoclasm was initiated in the first half of the eighth century by Emperor Leo III the Isaurian. At the source of this heresy stood yet another person, enigmatic and sinister: a certain Beser. He was a Byzantine military commander who had fallen captive to the Arabs, converted to Islam, and managed to become a vizier to Caliph Yazid II. Beser became close to certain rabbis and, with their help, convinced the Caliph to begin a persecution of Christians. This persecution was carried out in the form of iconoclasm: the destruction of “human images” and their defenders. (It should be noted that the Islamic world has not known such cases either before or since the time of Beser’s incitement. St. John of Damascus, an outstanding defender of the veneration of icons, soon became one of the Caliph’s Christian courtiers. Subsequently, the majority of monks fleeing from the fury of the iconoclasts found refuge among Arab Muslims.)

Iconoclasm was initiated in the first half of the eighth century by Emperor Leo III the Isaurian. At the source of this heresy stood yet another person, enigmatic and sinister: a certain Beser. He was a Byzantine military commander who had fallen captive to the Arabs, converted to Islam, and managed to become a vizier to Caliph Yazid II. Beser became close to certain rabbis and, with their help, convinced the Caliph to begin a persecution of Christians. This persecution was carried out in the form of iconoclasm: the destruction of “human images” and their defenders. (It should be noted that the Islamic world has not known such cases either before or since the time of Beser’s incitement. St. John of Damascus, an outstanding defender of the veneration of icons, soon became one of the Caliph’s Christian courtiers. Subsequently, the majority of monks fleeing from the fury of the iconoclasts found refuge among Arab Muslims.)

It seems as though, having incited the persecution of Christians in the caliphate, Beser had accomplished his mission there. He returned to Constantinople and demonstratively “re-converted” to Christianity. The Emperor Leo the Isaurian extolled this shady plotter, who had already stained himself through apostasy and treason, and made him his favorite. Spurred on by Beser, the Emperor decided to strike a blow against Christ’s Church.

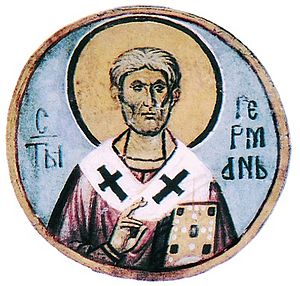

The Holy Patriarch Germanus of Constantinople warned Emperor Leo that worldly authority did not have the right to judge the truths of faith; this was the prerogative of the Ecumenical Councils. St. Germanus stated: “I am ready to shed my blood for the image of my Christ, Who shed His Blood to renew the fallen image of my soul. It is clear that impiety brought against the image of Christ is applied to the Prototype, that is, to Christ Himself. Likewise, honor given to His image is also applied to the Lord. Therefore it is befitting for us, faithful servants of Christ, even to die for the veneration of our Lord.” However, neither the words of the Patriarch nor any reasonable arguments could convince Emperor Leo the Isaurian, that “first and most evil iconoclast – nay, Christoclast.”

The Holy Patriarch Germanus of Constantinople warned Emperor Leo that worldly authority did not have the right to judge the truths of faith; this was the prerogative of the Ecumenical Councils. St. Germanus stated: “I am ready to shed my blood for the image of my Christ, Who shed His Blood to renew the fallen image of my soul. It is clear that impiety brought against the image of Christ is applied to the Prototype, that is, to Christ Himself. Likewise, honor given to His image is also applied to the Lord. Therefore it is befitting for us, faithful servants of Christ, even to die for the veneration of our Lord.” However, neither the words of the Patriarch nor any reasonable arguments could convince Emperor Leo the Isaurian, that “first and most evil iconoclast – nay, Christoclast.”The first act of iconoclasm was one of flagrant blasphemy performed in the sight of all. An imperial officer climbed up the Chalke Gate, which led into the palace courtyard, and with an axe began to strike the face of the image of Christ located there. A crowd of believers, indignant at this monstrous outrage, threw this blasphemer to the ground and tore him to shreds. The Emperor Leo ordered these “rebels” to be executed: thus suffered the first glorious martyrs for the holy icons. (Russia saw similar desecrations of holy things in this [twentieth] century. The Bolsheviks decided to demolish the memorial for the Grand Duke Sergei [Alexandrovich], assassinated by terrorists, which was in the form of Christ’s Cross. Lenin, surrounded by his henchmen, personally threw a noose around the neck of Christ the Savior. This was done in the sight of all – but, unlike the Byzantines, the Russian people remained silent.)

News of this unprecedented sacrilege in Constantinople spread near and far. Ellada rose up. Angry epistles were sent to the Royal City from the Churches of Europe. The Orthodox people did not want to see the desecration of their holy things. Seeing that his throne was tottering, Leo the Isaurian relented somewhat in his zeal for heresy.

The iconoclasm of the Byzantine Emperors caused the collapse of united sovereign power in East and West. Such was the earthly fruit of the heretical Caesars, whom some contemporary historians praise as successful military leaders and reformers.

Leo the Isaurian’s successor in this evil work, driving iconoclasm to an extreme of ferocity, was his son, Constantine V. This Emperor has gone down in history as Constantine Copronymus, that is, the Dung-Named (which is the literal translation of a much stronger word). Copronymus received this name in childhood because he defecated in the baptismal font. This horrified his godfather, the Holy Patriarch Germanus, who predicted: “This child, when matured, will profane the Church’s sacred objects with heresy and shed much blood of the pious servants of Christ.” Having a passion for all manner of excrement, Copronymus distinguished himself subsequently as well: he enjoyed smearing himself with horse manure, assuring everyone that it was very pleasant and salubrious.

It would be difficult to imagine a more loathsome personality than Constantine Capronymus. Insatiable in cruelty and debauchery, a lascivious butcher and sodomite, he died from one of the worst forms of syphilis. Capronymus harbored a pathological hatred towards all things sacred; his blasphemies against the holy faith, which the chronicler relates with a shudder, are truly monstrous. For greater mockery of the Church, Capronymus involved a certain defrocked monk in his drunken orgies, calling him the “merry abba.” (All of which is quite reminiscent of the “All-Drunken Most-Jesting Council” of the Russian Tsar Peter I. This sovereign was also a sadist, blasphemer, and butcher of the Church; and, as if that were not enough, a filicide. However, while Greek historians gave Constantine V a fitting epithet, in Russian history Peter I is persistently called “the Great.” It is an act of extraordinary blindness to ignore the fact that, long before Lenin and Stalin, this “great” Peter broke the backbone of the Russian people.)

This vessel of every kind of abomination, Constantine Copronymus, dared to philosophize about the All-Pure Divinity! Astonishingly, the Dung-Named “theologized,” writing an extensive treatise in which he “demonstrated that icons should not be worshipped.” His flatterers called him the “thirteenth Apostle”: indeed, Copronymus could well be likened to Judas Iscariot.

The Emperor did not confine himself to his foul “theology”: by his orders a mass extermination of the Orthodox, monastics first and foremost, was carried out. All the numerous holy monasteries in the Royal City were devastated, their property confiscated by the imperial treasury. Monks were subjected to brutal torture: their noses and ears were cut off, their hands were chopped off, their beards and faces were set on fire, and thousands of them were blinded and exiled to the mines. Many were buried alive. St. Stephen the New, a remarkable ascetic struggler, was dragged out of a cave and stoned: for this the schoolchildren of Constantinople were freed from their lessons and forced to take part in the saint’s murder. Clergy and laity suspected of venerating the holy icons were dealt with in like manner.

By order of Copronymus, mosaics were destroyed, frescoes plastered over, and icons burned, all created by generations of pious masters. The incorrupt relics of God’s saints had earlier been sent to Constantinople, as to the treasury of the Church, from all ends of the Empire. Now they were destroyed. According to an eyewitness, “the very rumor of the holy relics of saints has vanished.” Heretical madness reigned in the Royal City.

Copronymus wanted to give his attack on Christ the appearance of “ecclesiastical legality.” For this purpose he convened a “council” that has gone down in history as a “robber council.” This assembly was preceded by a purge of the clergy: the massacre of persistent icon-venerators. (The subsequent “robber council” during the reign of the iconoclast Emperor Leo V the Armenian was held in just the same atmosphere.) Only the corrupt and the cowardly remained, who out of servility or fear were prepared to sign anything the Emperor wanted. One of the repentant participants of this “imperial function” cried out: “Where there are swords and sticks, what kind of a council can this be?” The iconoclasts resorted to forgery in the interests of confirming their heresy: they displayed panels with iconoclastic utterances allegedly belonging to the Holy Fathers of the Church. Meanwhile, the heretics covered their tracks by ripping out pages from books written by the Holy Fathers that called for the veneration of the holy images; sometimes they simply burned patristic works. Yet, despite all the deceit and fury of the persecutors, the faithful continued to defend the holy icons.

Emperor Leo IV the Khazar, who succeeded Copronymus, was also a heretic. However (fortunately for the Church) he was engaged more with earthly politics than with questions of faith; during his reign the passion of the iconoclasts subsided. Empress Irene, the widow of Leo IV, did everything she could to restore peace and the purity of true faith to the Church. The Seventh Ecumenical Council was convened during her regency, under the chairmanship of the Holy Patriarch Tarasius of Constantinople.

The Fathers of the Council easily exposed all the evildoing of the heretics, unanimously decreeing:

“We affirm that we preserve all the traditions of the Church which have been decreed to us in her, whether written or unwritten, without innovation, of which one is the formation of representative images, which is perfectly concordant with the history of the Evangelical preaching unto the assurance of the true and not the imaginary Incarnation of God the Word, and which is of service to us unto a like edification. For those things which are naturally illustrative of each other most indubitably possess the outward appearance of each other… Whether images of Christ Jesus our Lord, our God and Savior, or of our spotless Lady, the Holy Mother of God, or of the Holy Angels or of all the Saints and other holy men. For in proportion as these are continually seen by representation in images, so are they who behold them moved to the remembrance of, and affection for, their prototypes.”

However, the Orthodox Church enjoyed this grace-filled peace for less than thirty years. The voice of the Fathers of the Seventh Ecumenical Council, inspired by the Holy Spirit, was drowned out by the growling of a new beast on the throne: Emperor Leo V the Armenian.

Leo the Armenian made iconoclasm systemic, creating an atmosphere of total surveillance and denunciation. Keeping holy icons was regarded as a state crime. Imperial spies roamed everywhere; the persistent fear of persecutors compelled many to become faint-hearted and to repudiate their holy things.

During this difficult time, it was as if St. John the Forerunner himself rose as a strong-spirited warrior for Christ in the battle against heresy. As far back as the fifth century, the pious proconsul Studios had raised a magnificent church in the Royal City in honor of the Lord’s Forerunner, in which a monastery called the Studion was established. The infernal Copronymus devastated this monastery along with the others in the Royal City. When calm returned to the Church, that great ascetic struggler, St. Theodore, renewed the Monastery of the Forerunner at Stoudios. He compiled the beautiful hymnography in honor of St. John the Baptist. St. Theodore the Studite, Abbot of the Monastery of the Forerunner, opposed Leo the Armenian’s evildoing with flaming words.

St. Theodore was thrown into prison, tormented by hunger and thirst, and subjected to torture and all manner of abuse. But even from confinement, the holy confessor did not cease to call upon the faithful to defend the veneration of the icons, to encourage the faint-hearted, and to inspire people to heroism in the name of Christ the Savior. St. Theodore the Studite’s voice was heard throughout the entire Christian world.

The evil heretic died an evil death: Leo the Armenian was killed as the result of a palace conspiracy. He was killed in church, in the very altar, to which he had run in an attempt to hide from his pursuers. The Emperor seized a cross from the Holy Table, with which he began to strike at his murderers; but they cut off the hand that was holding the cross, and then his head. Seeing in this God’s righteous retribution, St. Theodore the Studite wrote: “It was fitting that he who had desolated the divine churches should see swords bared against himself in the Lord’s church. It was fitting that he, who had destroyed the divine altar itself, should find no shelter from the altar.”

The terrible death of Leo V did not mean an end to persecution, which gained particular ferocity during the reign of Emperor Theophilus. The heretics engaged in the extermination of icon-painting masters. Iconographers could save their lives only by agreeing to spit on icons and trample them underfoot. Those who did not agree to this sacrilege were executed after brutal torture.

Among those captured by the persecutors was the remarkable iconographer, St. Lazarus Zographos. For his refusal to trample on the holy things, he was lashed with oxhide whips and then had red-hot iron plates placed in his hands so that he could never again be able to paint icons. The pain was so severe that the confessor lost consciousness and nearly died.

St. Lazarus was released from prison following the tearful entreaties of the Emperor’s wife, the pious Theodora. The first thing the holy iconographer did upon release was to paint an icon of John the Forerunner and Baptist of the Lord with his scorched hands. This icon immediately showed forth the grace-filled power of healing and became renowned for working miracles. Thus did the Lord’s Forerunner, through his holy image, strengthen Christians in upholding the holy icons.

When the truth of icon-veneration had triumphed definitively, the honor fell to St. Lazarus Zographos to install an icon of Christ in the very place where the mad heresy had begun. St. Lazarus painted an icon of the Savior on the Chalke Gate, opening to the palace courtyard, from which the iconoclasts had earlier toppled the icon.

St. Lazarus magnanimously prayed for his torturers his entire life, and the Lord heard his prayer. The holy iconographer’s tormentor, Emperor Theophilus, repented before his death and was forgiven by the Fathers of the Council of Constantinople in 843.

The Council of Constantinople once again – and definitively – affirmed the right of the faithful to venerate the holy icons. It was then that the radiant feast of the Triumph of Orthodoxy was established. The Holy Patriarch Methodius, a multitude of clergy, the Empress Theodora, her young son the Emperor, and jubilant crowds of people walked through the Royal City with holy icons, placing them in all the churches of the city.

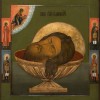

Having returned to the true faith, the capital of the Empire once again began to be adorned with holy things. The incorrupt relics of the Holy Patriarch Germanus and of St. Theodore the Studite were brought to Constantinople, the first sacred bodies of passion-bearers who had suffered under the heresy of iconoclasm to appear there. Then one of the greatest of sacred objects, the head of the Lord’s Forerunner, was also returned to the Royal City.

St. John the Baptist appeared in a vision to Patriarch Ignatius of Constantinople, showing him where his precious head was hidden. It was found in Comana and, to the great joy of the Orthodox, once again returned to the reigning city, where it was made available for veneration. Once again a stream of miracles gushed forth onto the faithful from the Baptist’s divinely-wise head.

The victory over the heresy of iconoclasm laid the foundation for the universal feast of the Triumph of Orthodoxy, which from then to the present day has been celebrated by all the Local Churches. This triumph placed a full stop, as it were, to Orthodoxy’s centuries-old struggle with distortions of the holy faith, instilled by the devil through vain heretics.

Since the time of the Seven Ecumenical Councils, which unmasked various forms of satanic falsehoods, heretics have not invented anything essentially new. Many current “theologies,” akin to the ancient Arians, make every effort to belittle the Divinity of Christ the Savior. Contemporary Protestants, like the ancient Nestorians, refuse to venerate the Mother of God. Today’s occultists, like the Origenists anathematized by the Church long ago, theorize about the transmigration of souls. And one can find the fundamentals of iconoclasm in that motley accumulation of heresies called Protestantism.

An explosion of iconoclast passions marked the appearance of Protestantism in the sixteenth century. The diabolical Forel rushed to Switzerland with a horde of fanatics to break into churches and destroy icons. Many Protestant sects have subsequently distinguished themselves by an equally ferocious iconoclasm. Even in this [twentieth] century, sectarians destroyed icons in Mexico. These latest “zealots” have taken this ancient heresy to its extreme: unlike them, the Byzantine iconoclasts did not refuse to venerate the Cross of Christ, which is directly prescribed in Holy Scripture. These new iconoclasts have gone so far as to become stavroclasts.

A significant portion of the blame for the emergence of Protestant iconoclasm lies at the feet of the Pope of Rome. Roman apostasy led to a distortion of the very essence of iconography. The Orthodox East has been shaken by the pretentions of Emperors to ecclesiastical authority, that is, by caesaropapism. In the West, the bishops of Rome attempted to arrogate to themselves the fullness of secular power and simultaneously to gain sole dominion over the entire Church of Christ. Within Orthodoxy an antidote to caesaropapism has remained: the conciliar mind of the Church as the Body of Christ. But in the West there was no antidote to papocaesarism, inasmuch as the Roman Pontiffs dared replace the only Head of the Church, Christ Himself, with themselves.

The West, having been corrupted by Papism, found itself defenseless in the face of the spiritual arbitrariness of the Popes, among whom one could find men who, in terms of depravity, were hardly inferior to the Emperor Copronymus. The licentiousness of the Papal Curia transmitted itself to the mass of believers. This plague also struck artists who painted sacred images, who lost their sense of reverence and began to treat their holy work like an ordinary craft. In the West, icons degenerated into paintings of religious scenes, sometimes even of a seductive nature. They frequently reached the point of blasphemy: artists produced portraits of their girlfriends as depictions of the “Madonna.” Among the traditions of the Ancient Church are cases when the hands of such iconographers simply withered. In more modern times, the Lord sent the plague of Protestantism on proud Rome.

However, in the heat of their righteous indignation against Papal abuses, the Protestants did not notice that they themselves had withdrawn even further than the Latins from Divine Truth. They “threw out the baby with the bath water,” and with martial fervor rejected the Mysteries and Tradition of the Apostolic Church, pushing aside the saving hand of the Orthodox Patriarchs. Protestantism was left in a deadly and grace-less emptiness, disintegrating into a multitude of sects.

In the Ancient Church, iconography was a sacred activity engaged in by pious people, largely monks. The clergy designed the iconic images; iconographers simply fulfilled these designs. Ancient piety gave birth to the canons of holy icons, the contemplation of which can elevate the human soul and guide the worshiper’s thoughts to Heaven. Even in our days, despite the decline of iconographic skills, the Orthodox Church has preserved these canons and vigilantly monitors the spiritual nature of sacred images.

Protestants, like the ancient iconoclasts, continue even now to shout: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image,” referring to the holy icons. They are spiritually blind: they do not want to see that Orthodox Christians do not worship wood and paint (just as by venerating the Bible they are not worshipping paper and ink). The Lord gave us sight, as with all the senses, not for senseless or foolish use, but for being illumined by the Divine Light. By contemplating holy icons with pure eyes, Christians can ascend in mind and heart to the Heavenly Kingdom and there worship our Savior, the God-Man Christ, His Most-Pure Mother, and all the holy people who are friends of God. The Incarnate Lord and His righteous saints trod on this very earth. The memory of their images is sacred to us, helping us sinners to follow the path of salvation.

Like the ancient heretics, Protestants also reject the veneration of holy relics. But for us Orthodox, the incorrupt bodies of the saints, and the miracles that emanate from them, are visible testimonies to the resurrection of the faithful into the glory of the eternal Kingdom of the Heavenly Father. The saints of God are alive, they are with us and help us; their precious relics, which we venerate, are a pledge of this. Among these saints is our mighty helper, John the Forerunner and Baptist of the Lord, a portion of whose head is now preserved in the heart of Orthodox piety, the Holy Mountain of Athos.

Beloved brothers and sisters in the Lord!

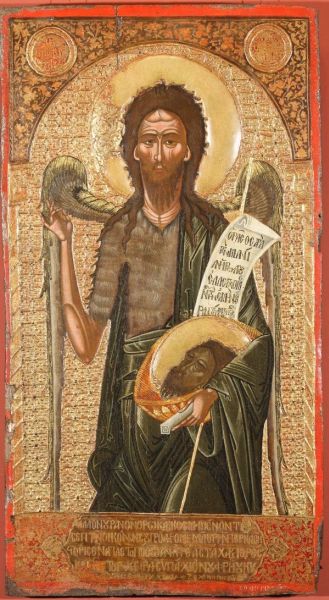

On some icons of St. John the Forerunner we see something that might seem strange to us. The Forerunner’s head is on his shoulders, and another head, this one severed, is held in his hands. There is a lofty spiritual meaning to this depiction, so incomprehensible to the worldly. Christ’s Forerunner, having been beheaded by the wicked, has risen intact and in power and glory in the Heavenly Kingdom. Yet he has granted his earthly head, radiant with his divinely-illumined mind, to the faithful living on earth, inspiring us to deeds and struggles leading to Eternal life and glorification.

The Lord’s Forerunner preserved the Savior’s image in his heart and mind; he preached Christ’s coming with his lips. All of St. John’s qualities, and his entire being, were united in his flaming love for the Almighty, just as the Holy Fathers command us to unite mind and heart in prayer and, in unity of thought and feeling, to aspire wholly to Heaven.

We normally celebrate the first and second findings of the precious head of God’s Forerunner either in the days leading up to Great Lent, or in the days of Lent themselves, while we celebrate the third finding after Christ’s Pascha. Thus, both during the days of abstinence and the days of spiritual exultation, we should approach the Forerunner’s lofty mind, warmed by the love of Christ, in order always to keep our minds in gladness, sobriety, and the light and joy of the love of God.

Thus, may the Sweetest Christ the Lord reign in our minds and souls, through the prayers of His Forerunner, to whom we cry: “Rejoice, for by God’s providence thy head was preserved incorrupt! Rejoice, for it has granted consolation, sanctification, and healing to Christians! Rejoice, great John, Prophet, Forerunner, and Baptist of the Lord!” Amen.

Translated from the Russian.