Vol. 3 No. 4 – Holy Cross 2008

“No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one, and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other.” – Matthew 6:24

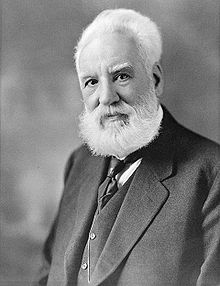

Alexander Graham Bell

Ironically, Bell himself knew the risks of his own invention. After his discovery had become more commonplace later in his lifetime, Bell refused to have a telephone installed in his study, out of a concern that it would be a distraction, and would undermine more serious work. Bell was the first to admit the capacity for communication to descend into time-wasting trivialities and mere entertainment. The applications of his work at the beginning of the twenty-first century demonstrate just how prophetic his understanding would be.

The modern world can credit Bell with pioneering the technology that knits together world banking and commerce, as well as reducing isolation and connecting people with shared interested, including church communities and families separated by distance, as Bell himself experienced as an immigrant to Canada. Like any lost traveller in rural Canada, Bell would have marvelled at the opportunity to obtain instant travel directions. As a researcher and scientist at heart, Bell would no doubt have been impressed with the overwhelming availability of online texts, the ease of communication afforded academic researchers, and the speed with which rare books can be located, purchased, and received without leaving the warmth of home.

Yet for the generation which grew up after the demise of the dial phone, Bell’s inventions and their progeny are the underpinnings of something more than means of communication. They have revolutionized the way in which human being relate – or don’t relate – to one another. While Bell’s own work with communication opened many doors of human connectedness (particularly his work with deaf students such as Helen Keller) he would lament the dehumanizing effect that technology has often brought to communication today.

Bell saw the capacity for technology to enhance the emotional intimacy of life as it should be lived; he could not have foreseen a time when information would be customarily exchanged in the emotional vacuum of emails or text messages, which offer a shadow of real human contact, but which cannot convey the living thought and feeling of the human person. For many raised in the field of Blackberries, one-dimensional techno-talk has become a substitute for human intimacy. In many cases, it is hardly recognized as a problem.

The father of the telephone did foresee the growth of intrusive communication, and could have possibly predicted the need for filtering communication. Bell himself would have considered most telephone conversations the verbal equivalent of junk mail, and would likely have understood most emails as an inconvenience. One can only guess what the dour old Scot would have had to say about text messaging.

For Orthodox Christians, the benefits of telephone-based technologies – especially the Internet which grew out of them – are numerous. Yet for those who come from the neptic tradition of the Church Fathers, and who take seriously the spiritual discipline of guarding the senses, Bell’s grandchild, the Internet, is heir to a multitude of less-than-noble features, which pose real spiritual dangers.

The pop guru Andy Warhol suggested that there would come a time when everyone would experience fifteen minutes of fame. For Orthodox Christians, these words come as a warning that we must be constantly vigilant regarding the spiritual side of investing our energies in self-promotion over the Internet. Websites are one level of this phenomenon; Facebook and similar networking sites are another level. The idea that private life would become the constant fodder for public view, and that regular individuals would become celebrities, would make Warhol and Bell shudder – not to mention the deep sadness it would evoke in the hearts of the Church Fathers.

One must rightly ask: is this sort of thing Christian? Do people who are struggling to become holy, to have some victory over the passions, properly engage in this kind of self-promotion? How does this help – or hinder – our salvation? This is not a question of eschewing technology in neo-Luddite style, nor is it a question of the promotion of a business or a charitable cause, for which one might argue technology can be a useful and even benevolent tool. This is a question of man making himself a celebrity for no other reason than the desire to be a celebrity. This is man making himself god.

For Orthodox Christians (including bishops and priests), there is also the temptation of virtual spirituality, the growth of online “experts”, easily detached from spiritual guidance, or church community life. The growth of this phenomenon bears a noteworthy parallel to the decline in the number of faithful partaking in weekly Holy Communion and Confession, both of which require a physical presence. What might have once been called arm-chair spirituality in the era of television, is now accepted as a norm, where spiritual critics trade arguments and often insults in online “theological discussions”. This exchange is often far removed from what the Church would recognize as theology – the knowledge of God (Theos) the Word (Logos). Rationalistic theorising has replaced the knowledge of God, and in the fast paced age of instant communication, the change often goes unnoticed.

The rise of technology has also contributed to the phenomenon of perpetual availability. A growing number of Canadian employers offer their staff free Blackberries for personal use, with the understanding that the employees will make themselves available for contact by the employer at all times. For some, this is seen as a status symbol. In reality, it calls Orthodox Christians to come to terms with a new kind of slavery, one which dominates every moment of our time – waking and asleep, on the job or at home – pacifying us with the technological chains that make for happy slaves.

Such monopolization of time has consequences. Gone are the days where most Orthodox Christians marked the regular feasts of the Church by attending divine services on feast days: work takes precedence. Weekends which used to offer some respite of personal time (when they are not flooded with more work hours), are now often crowded with social commitments facilitated by the easy distraction of instant message invitations. Where slaves in the early Church rose before sunrise to receive the Holy Mysteries each day, free citizens in prosperous countries today struggle to make it out the door for Sunday Liturgy. Technology has played a significant role in this change.

One of the greatest challenges of the Christian life is making time for prayer. Once the time is made, the greatest challenge is persevering through our prayers to completion (not to mention the added struggle of offering our prayers with compunction of heart and a sincere mind). The drive for perpetual accessibility changes all this. Even when the cell phone is turned off, even when email is not up on the computer screen, or the blog or Facebook status has been updated, the pressure for timeliness – the need to have the latest news, and the latest message – is perpetual. If we can be reached at any time, if we are never able to devote ourselves one hundred percent to any activity without the prospect of being called away, we are not in fact masters of our own lives, nor can God be our Master. We are slaves to another, or to many others.

For several years, I made the daily journey back and forth to the “Telephone City” of Brantford, Alexander Graham Bell’s home, the birthplace of all the technological stuff that clutters our everyday life and challenges the time we devote to the struggle for repentance. The visible landscape of this little corner of Upper Canada has changed little since Bell’s time: a patchwork of farms and tiny villages, tractors and friendly faces between market towns and pottery barns.

Yet the inner landscape – the landscape of the human heart – continues to face the same struggle in the Telephone City that it does in every city, town, and home across our country. Like our daily drive through Brant County, it can be a landscape free of ringtones and online chat and graphic Facebook images, a peaceful wandering in a quiet land where the Lord is our only Mapquest.

Or it can be something very different, something which Alexander Graham Bell knew well when he refused to have a phone in his study, for the man who invented the original ringtone recognized that silence is indeed golden.

Source: Orthodox Canada – A Journal of Canadian Orthodox Christianity