Source: St Elisabeth’s Orthodox Church, Wallasey, United Kingdom

Preface

My lord bishops, honoured hieromonks, archpriests, presbyters, fellow deacons, and beloved brothers and sisters in Christ, I greet you with the words of our Saviour:

If anyone serves me, let him follow me; and where I am, there also shall my servant be; if any one serves me, the Father will honour him.

– John 12: 26

I would like to begin my talk on the Diaconate in the Church by giving you some examples of deacons, so that you can better understand what a deacon is, what he does, and also something of the flavor and spirit of the diaconate in actual circumstances.

In the account of the martyrdom of Saints Perpetua and Felicitas, we learn that these women were among five catechumens who were the first victims of the persecution in 203 AD at Carthage by Septimus Severus. Saint Perpetua was a high-born, well-educated, young woman of pagan parents who was married with a suckling child. Felicitas was a slave who was eight months pregnant and they were both baptized between the time of their arrest and their imprisonment. Here are a few excerpts from Saint Perpetua, who left a written record of the events of her imprisonment:

Tertius and Pomponius, those blessed deacons who were ministering to us, paid for us to be removed for a few hours to a better part of the prison and refresh ourselves. My baby was brought to me, and I suckled him,…

And later we learn:

…I sent at once the deacon Pomponius to my father to ask for my baby. But my father refused to give him.

Finally, just before they were to be taken into the arena to be killed, we read:

on the day before we were to fight, I saw in a vision Pomponius the deacon, come hither to the door of the prison and knock loudly. And I went out to him, and opened to him. Now he was clad in a white robe without a girdle, wearing shoes curiously wrought. And he said to me: ‘Perpetua, we are waiting for you; come.’ And he took hold of my hand, and we began to pass through rough and broken country. Painfully and panting did we arrive at last at an amphitheater, and he led me into the middle of the arena. And he said to me: `Fear not; I am here with you, and I suffer with you.’ And he departed. And I saw a huge crowd watching eagerly…

By attending carefully to this dramatic narrative, we learn a great deal about the diaconate in the early Church, and what the deacons did. We learn from Saint Perpetua’s account that two deacons ministered to them regularly, interceding with the authorities and guards to improve the condition of the catechumens, arranging for their baptism, acting as intermediaries between the prisoners and their families, and encouraging them to remain strong in their witness to Christ. After their baptism the deacons also carried Holy Communion to them as was customary for deacons to do for those unable to attend the eucharistic gathering.

The next example is that of the blessed Archdeacon of Rome, Saint Laurence, whose function included caring for the sacred vessels of the church and distributing money to the needy. About the year 257AD, a harsh persecution was raised up against the Christians by Valerian, and the Archdeacon was arrested and brought before the Prefect. When questioned concerning the treasures of the church, he asked for three days’ time to prepare them. He then proceeded to gather all the poor and the needy, and presented them to the Prefect and said, ‘Behold the treasures of the Church’. The Prefect became enraged at this and commanded that Laurence be racked, scourged, then stretched out on a red-hot iron grill. Finally, enduring all without groaning, his face like that of an angel, he prayed for his slayers in imitation of Christ, and gave up his spirit on the 10th of August, 258 AD.

Within fifty years we see how the deacons had already become known as the “money bags” of the Christians, and as such became primary targets during the persecutions. If we read the documents of this period carefully, we come to understand that the deacon’s activities in tending to the needs of the faithful—the widows, orphans, the sick, the imprisoned, those absent from the Liturgy, etc.— made them highly visible to the authorities and easily recongisable. From an organisational point of view, the Roman authorities felt that eliminating the leaders of the Christians (the bishops and presbyters) was the most effective means of stamping out the hated sect; but from a practical point of view it was highly lucrative to seize the treasuries of the Christian communities, held by the deacons. In fact, these financial resources were not insignificant. For example, in the life of Saint Porphyry, Bishop of Gaza, written around 410 AD by his attendant, Deacon Mark, we learn that the deacon went from Jerusalem to Thessalonica to sell the Church’s possessions as he was instructed by the Bishop, and received some 4,500 pieces of gold to be used for the charitable work among the faithful. This was a considerable amount of money in those days.

Anecdotally, we know that this same Deacon Mark was sent twice to Constantinople by his bishop to ask the Patriarch, Saint John Chrysostom, to intercede in behalf of the Christians who were being persecuted by the idolaters in Gaza. When, after his first visit to Saint John, he didn’t receive a prompt response, like any good deacon, he went every day persistently to visit the Patriarch, and reminding him of the importance of the mission until a decision was reached. On his second visit, the Deacon was also received by Empress Eudoxia and no doubt comported himself with perfect acumen.

We turn now to the third example of the diaconal ministry which deals more with the liturgical aspects of the diaconate. In the Primary Chronicle, compiled around 1037 AD, we have a description of how Prince Vladimir sent his emissaries West to ’learn about their faith’. After returning from their visits to the Latins, Jews, and the Moslems, they were sent to Byzantium with the same mission.

The Chronicle records the following about that visit:

…hearing this, the partriarch ordered that the clergy be assembled; and according to custom they held a festival service, and they lit the censers and appointed the choirs to sing hymns. And the Emperor went with them into the church and placed them in an open place; and he showed them the beauty of the church, and the singing, and the serving of the arch-priest, and the serving of the deacons, and he told them about the service of his God, and they were in amazement and wondered greatly and praised the service.

Overwhelmed by what they had experienced in the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, they reported the following to Prince Vladimir:

We knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth. For on earth there is no such splendor or such beauty, and we are at a loss to describe it.

We can deduce that what impressed the Russian delegation so forcefully was what they saw and perceived when the saw the procession of deacons entering on the north side of the nave with the prosphoral offerings that were prepared for the Anaphora. Records indicate that at any one time there were from 80 to 120 deacons attached to the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia, and it is indeed mind- boggling to try to recreate what this procession must have looked like: an army of deacons, with censers, accompanied by subdeacons, candle bearers and others entered the church to present the “prosphora,” the offering of the whole Church to the celebrants as the choir raised its hymn to praise the Risen Lord. With these three historical examples of the deacon’s ministry, we can turn now to a further explanation of the diaconate as a function within the Church.

The Ministry of the Deacon

The ministry of the deacon is based in the ministry which Christ performed for us. This ministry is one of service and is expressed by Christ with these words:

I am among you as one who serves.

With these words Christ reversed the order of things, for He who is higher than the heavens became a servant for our salvation. The master becomes a servant and makes service to others the path of salvation.

You know that the rulers of the Gentiles Lord it over them, and their great men exercise authority over them. It shall not be so among you; but whosoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whosoever would be first among you must be your slave; even as the son of man came not to be served but to serve, and to give His life as a ransom for many.

Because, therefore, service to others is the content of Christ’s life it must be the same for all Christians. Service is basic to Christian spirituality for it is by our unselfish and obedient service to others—with all the suffering and humiliation that this implies—that we participate in the divine life of God.

This minstry of service was left as a legacy to the Church and is bestowed creatively by the Holy Spirit not only as the sign and function of the Church, but also as the basis of our unity in the Church as the Body of Christ. This legacy carries with it the power to sustain sonship in the Kingdom of God now and was given as a gift for the salvation of man. But even though service is our inheritance as Christians, and our birthright as members of his Body, Christ also set aside individuals in whom this service is made personal as a function performed for the Church, and in whom this service is a specific ministry given by God. In these individuals, who are the official ministry, (bishop, priest, and deacon), the ministry of the Church is extended among its members in organised worship and mutual assistance, as well as the mission of the Church and Her service of witness in the world.

The Apostles were the first to receive this function of service from Christ and they in turn set up an official priesthood to insure its continuation in the Church. They appointed the first bishops and deacons so that Christ’s ministry might be extended and maintained for the salvation of all.

The Diaconate

In the above, the words service, servant, and ministry can be substituted by the words deacon, deaconing, or diaconate. Holy Scripture uses these words in this way. Literally, deacon means servant or waiter. Very early in the Church, as recorded in the Book of Acts, the words deacon and diaconate came to be used as the designation of a specific office, part of the official ministry of the Church. The Book of Acts tells us that, with the expansion of the Church, the Apostles were unable to perform all that them as travelling ministers of the word. They appointed bishops to preside over the Christian communities so that they might continue their preaching. Deacons were also chosen from among the faithful to assist in the work of the Church and as co-workers with the bishops.

Originally, seven deacons were chosen and their duties were twofold. First they had the responsibility of gathering the food and other goods which were brought to the Church as offerings, and of distributing these donations as the philanthropy of the entire community to the needy whom the Church supported. It was also their duty to prepare for the Eucharistic gatherings and the common meals in which the whole Church participated. Consequently, the deacon’s role was both to extend the Church’s charity to those who required it and to lead the people in the liturgical gatherings.

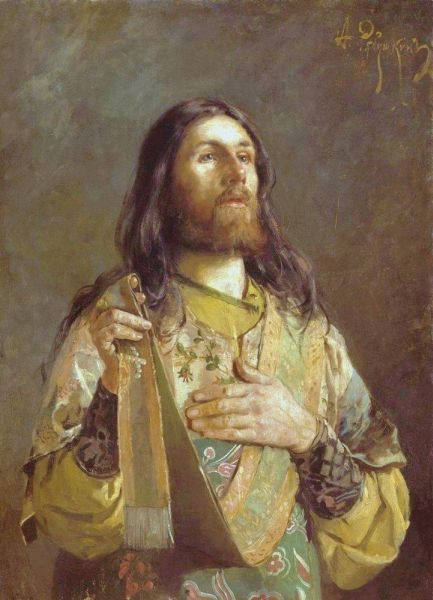

This idea of serving at tables very early influenced their comparison to angels, for just as the angels serve God, deacons serve the heavenly banquet of the holy Church. Consequently the form and design of diaconal vestments reflect not only their comparison to angels, but also the practicality of their service at the altar and their relationship to the bishop. Because of this, the deacon’s stole (orar), with which he binds himself before approaching the Holy Table at the Anaphora, is often compared to the wings of the angels. So too both the deacon’s stole and cuffs are often stamped with the words: Holy, Holy, Holy, – the hymn which the angels sing as they surround the throne of God. Seraphic representations are used on all the diaconal vestments to signify the seraphic ministry at the heavenly Throne. The deacon’s stikhar originated from the dalmatic, a form of tunic with large sleeves that came into use in the second century. Although it became the informal uniform for high officials and in the West by the fourth century was worn by important bishops, it was adopted as a normal dress by the seven regionary deacons of Rome. Significantly, deacons by that time, because of their role as ministers of charity for the Church, had already become superintendents of the whole poor relief system of the city and the estates which formed its endowment; and their duties were becoming administrative and financial rather than religious. The deacon’s stikhar (robe), moreover, is a longer version of the bishop’s sakkos, signifying his relationship to the bishop. The primary function of the deacon as server at the altar is manifest architecturally as well in that the north and south doors leading to the sanctuary are called Deacon’s Doors. They are traditionally adorned by icons of the Archdeacons Stephen and Laurence and/or the Archangels Michael and Gabriel dressed in diaconal vestments.

In his ministry of charity, the deacon moved among the people so as to learn their needs and bring these needs to the bishop’s attention for solution; and as such is equivalent to a social worker in modern terms. In the third century the Church in Rome supported 1,500 widows and needy, while in fourth-century Alexandria 3,000 needy were fed daily by the Church. Central to the deacon’s duties was visiting the sick and the imprisoned, caring for the demoniacs, responsibility for the widows and orphans, instructing the catechumens and preparing them for Holy Baptism, and taking Communion to those who are absent from the Eucharistic gatherings. Eventually the deacons also taught and preached the Holy Gospel. In all these actions he acted on behalf of the bishop (or priest) and the whole Church and was directly responsible to the bishop in all things. Categorically, the deacon is not an independent agent. Because of his dependence upon and close co-operation with the bishop, the deacon is often described as the eyes and ears of the bishop.

The works of charity which the deacon performs are integrally tied to this service as co-celebrant at the altar and emanate therefrom. Having collected the offerings of the faithful, the deacon chose what was necessary for the Liturgy, and prepared those elements necessary for the Holy Communion. All of the offerings were originally collected in the Diaconicon (also called Diaconry), a serparate room outside the church where vestments, holy vessels and food were kept, and where the bread and wine were prepared for the Holy Liturgy. Having completed the preparation of bread and wine for communion, the deacons left the diaconicon at the proper time and, entering the Church, proceeded to the altar where they presented these gifts to the celebrant as an offering of the people. This is the origin of our Great Entrance and the reason why even today the deacon carries the holy paten at the Entrance and announces:

All of us, and all pious and Orthodox Christians, May the Lord God remember in His Kingdom, now and ever and unto ages of ages.[i]

Just as the breads used for the divine service are called prosphora, (which means to offer to), so too the deacon’s function is one of prospherein, that is of offering to the celebrant the gifts of the people, which will be returned to them as the Body and Blood of Christ after they have been offered up (anapherein) at the altar.

Liturgically, it is the deacon’s function to bring the people together and unite them in corporate prayer and in their function of fulfilling their role as members of the Body of Christ, the Church. He may not give a blessing, however, since this right belongs solely to the priests and bishops. Rather he leads them in their offerings to the altar––through their material offerings (prosphora) and in their prayers— so that the celebrant may offer up (anaphora) their sacrifice unto God. Indeed, the diaconal function consists primarily of enabling the corporate action of the Eucharist to be fulfilled through the participation of all the members of the Body of Christ in their several functions at their proper time and in their proper order. In the words of a noted scholar[1] on function and the eucharist:

The corporate eucharistic action as a whole (which includes communion) is regarded as the very essence of the life of the Church, and through that of the individual Christian soul. In this corporate action alone each Christian can fulfil the ‘appointed liturgy’ of his order–his function–and so fulfil his redeemed being as a member of Christ…. Whereas in the pagan rites men attend ‘not to learn something but to experience something,’ the Christian eucharist is the reverse of all this. The Christian comes to the eucharist not ‘to learn something’, for faith is presupposed, nor to seek a psychological thrill. He comes simply to do something, which he understands as an overwhelming personal duty. It is in the doing of the eucharistic service, (his prayers and prosphoral offerings), that he expresses his intense belief that in the Eucharistic action of the Body of Christ, as in no other way, he himself takes a part in that act of sacrificial obedience to the will of God which was consummated on Calvary and which had redeemed the world, including himself. What brings him is the conviction that there rests on each of the redeemed an absolute necessity to take his own part in the self-offering of Christ, a necessity more binding even than the instinct of self-preservation. Simply as members of Christ’s Body, the Church, all Christians must do this, and they can do it in no other way than that which was the last command of Jesus to His own. That rule of the absolute obligation to be present at Sunday liturgy was burned into the corporate mind of historic Christendom. It expresses as nothing else can the whole New Testament doctrine of redemption; of Jesus, God and Man, as the only Saviour of mankind, Who intends to draw all men unto Him by His sacrificial and atoning death; and of the Church as the communion of redeemed sinners, the Body of Christ, corporately invested with His own mission of salvation to the world.

From the bishop to the newly confirmed, each communicant gives himself under the forms of bread and wine to God, as God gives Himself to them under the same forms. In the united oblations of all her members the Body of Christ, the Church, gives herself to become the Body of Christ, the sacrament, in order that receiving again the symbol of herself now transformed and hallowed, she might be truly that which by nature she is, the Body of Christ, and each of her members of Christ. In this self-giving, the order of laity–no less than that of the deacons or the high-priestly celebrant–has its own indispensable function in the vital act of the Body. The layman brings the sacrifice of himself, of which he is the priest. The deacon, the ‘servant’ of the whole body, ‘presented’ all together in the Person of Christ, as Ignatius reminds us. The high-priest, the bishop, ‘offered’ all together, for he alone can speak for the whole Body. In Christ, as His Body, the Church is ‘accepted’ by God ‘in the Beloved’. Its sacrifice of itself is taken up into His sacrifice of Himself.[2] On this way of regarding the matter, the bishop can no more fulfil the layman’s function for him than the layman can fulfil that of the bishop. When, in early church practice, the deacon collected the prosphora from the people and placed them upon the altar, the bishop and other celebrants each added prosphora to the people’s offerings on the altar. Thus the whole rite was a true corporate offering by the church in its hierarchic completeness of the church in its organic unity. The primitive layman’s communion, no less than that of the bishop, is the consummation of his ‘liturgy’ in the offering of the Christian sacrifice.

At the appropriate time, the deacon also returns these very gifts to the people after they have been consecrated to God and blessed by the Holy Spirit in the form of Communion. Receiving the holy Chalice from the celebrant, the deacon turns to the people and announces:

With the fear of God, faith and love, draw near.

At the altar, all the deacon’s actions are performed in behalf of the faithful and it is precisely his role as servant to the celebrant and people that makes him the bond of unity between the two. In this way there is not a single act of the Divine Liturgy where the faithful and clergy are not united in a common action and prayer, for the faithful are present at all times at the holy Altar through their offerings and the deacon’s presence as their servant.

During the liturgy, the deacon stands in the midst of the faithful as master of ceremonies, directing them in the proper posture and movements of the service. Let us bow our head unto the Lord and (Lock) the doors, the doors are examples of this. It was part of the deacon’s service to see that each of the assembled faithful—penitents, kneelers, children, chanters, hearers, servers, widows, virgins and catechumens – performed their proper function and participated in the Liturgy according to that function. The deacons also led the people in prayer, standing in their midst, asking for the peace of the world, for the union of all and for whatever other petitions or needs the faithful requested. In our liturgy today, the litanies (ektenias) have become standardised but are still called the deacon’s litany/ektenia. Originally, in addition to the standard petitions, the deacon also “composed” other petitions to express what the immediate, changing needs of the people were thereby bringing these needs to the Church for their help and prayers[ii]. Because he worked so closely with the faithful and dispensed the charity of the church, he knew who was sick, who had died, who was travelling, who was out of work or whose crops had failed, and included these needs in his litany. In this way, by announcing the “daily news and needs” of the faithful during the litanies, the deacon informed the faithful who needed help and for whom prayers were needed.

One author describes the ministry of the deacon with these words:

The deacon leads the people in their responses to God which is as the precious oil which causes the lamps of the sanctuary to burn brightly in the House of the Lord. The deacon is as the hand of the people stretched out to receive the blessing, as their ear attentive to hear what God the Lord will say, and as their mouth to answer with them: “Amen”.

The deacon is entirely responsible during the liturgy for the people’s actions and his function is to lead them by word and gesture, by prayer and petition to the altar in oneness of mind. His usual place, therefore, is in the midst of the faithful, to lead out those who are not to receive Holy Communion and then bar the doors so none else could enter who was not eligible to receive Holy Communion. The deacon also reads the Holy Gospel and, being responsible for instructing the catechumens in their preparation for baptism, he conducts them in and out of the church at the proper time.

Because of the deacon’s eucharistic service, his work among the people and his close relationship with the bishop (or priest)–from whom he derives his authority to act– he stands as a vital link between the clergy and laity. In the diaconate, the charismatic and institutional ministry of the Church is integrally allied to manifest the fullness of the Church.

Through this ministry, the idea of function is clearly expressed as is the principle of hierarchy and the unity of clergy and laity as the royal priesthood of the Kingdom of God. It is the diaconate, moreover, which as ministry for the people of God expresses the incarnate charity and love of the Church; and by this charity reminds the Church of her eschatological dimension. The deacon’s function also brings together the social and economic activities of man in the Church so as to transform them and offer them to the glory of God. Finally, the diaconate expresses both the spontaneity and fluidity of the Church’s forms as She reaches into the world, drawing from the never-ending riches of her storehouse of tradition, and sanctified by the Holy Spirit provides the constantly renewing and personal forms necessary to fulfil her ministry as the Body of Christ.

The entire scope of the deacon’s ministry, however, exists only because of his relationship to the bishop and as a servant to the community of believers. He is not a free agent. Rather his authority comes from the bishop and he may act only in the name of the head of the community, i.e. the bishop (or the priest). It is for this reason that the ordination of the deacon follows the consecration of the Bread and Wine: to show that he does not have the full power of the priesthood and cannot therefore consecrate, bless, or act as an independent authority.

Since the time of the Apostles, it had been the tradition of the Church to have seven deacons in each church. It later became the practice to ordain as many deacons as were necessary to meet the needs of the people. At one time 120 deacons and 80 deaconesses were needed in the Church of the Holy Wisdom (St Sophia) in Constantinople to fulfil the philanthropy, social work, teaching, and administrative needs of that community. The function of the deaconesses included most of the philanthropic and educational responsibilities of the deacon, but none of the liturgical functions.

History provides many examples that illustrate the full scope of diaconal service. In the Byzantine Empire deacons held some of the highest and most powerful positions. The magnificent mosaic of Justinian in St Vitale’s Church in Ravenna shows two deacons in the imperial entourage. In the patriarchal court, deacons were invested with the authority of exarch, protosyngellos, emissaries, ambassadors, and administrators of the episcopal household. Deacons often held important chairs and were professors at the patriarchal academy; they administered church-run and privately funded homes for the poor and widows, orphanages, hospitals, and what is equivalent to the half-way houses of today. Deacons attended the great councils of Church as in the case of St Athanasius who as a deacon participated in the First Ecumenical Council, and represented the patriarch at councils as their exarchs. In the case of Archdeacon Nicephoros, a martyr saint, the Council of Constantinople in 1592 bestowed on him the chairmanship for all consecutive councils with responsibility to make all decisions regarding the faith. He directed the affairs of the patriarchate for many years, and it was in his ministry as a deacon that he went to the Ukraine in 1595 as the patriarchal exarch to defend the rights of the Orthodox against the ruling Polish authorities, and was imprisoned, tortured, and martyred by the uniates when he spoke out in defence of the faith.

In the West, the function of the deacon went into decline by the 5th century and eventually disintegrated almost totally; consequently when Vatican II called for the reinstitution of the diaconate, there was no continuous memory or practice of that function as there is in the East; and even though there has been a substantial increase in the number of “permanent” deacons, they function as mini- priests. Their ministry does not reflect what the diaconate was created for. Although the title of archdeacon was retained in the West, the function was distorted to the point that there continued to be cardinal deacons who were, in fact, not deacons. Similarly, in the Anglican Communion the archdeacon wields enormous power, even though that function is not held by a deacon.

Today, in many Orthodox lands the diaconate has been decimated by the atheist governments which enslaved those lands while elsewhere most deacons are quickly ordained to the priesthood because of the shortage of priests. Nonetheless, the diaconate is still a vibrant, highly-visible ministry in the Church, with deacons leading the faithful as the master of ceremonies and serving the celebrant at every stage of the Eucharist. The ministry of the deacon is a vital sign of the well-being of the Church. Indeed because of the lack of deacons in each parish, there is a growing lack of understanding of what the diaconate is as a specific function. This lack can be directly tied to many problems which have arisen in the communities. The lack of unity among clergy and laity, the loss of spontaneity in liturgical worship, and the breakdown of the hierarchical structure are but a few of the problems which can be traced directly or indirectly to the disappearance of the deacon’s ministry. But perhaps the most serious consequence of the decay of the diaconate as a vital function of the Church is that the priest cannot fulfil his most important function of praying to our Saviour at the Holy Altar in behalf of his flock. Most often the priests have to rush through or omit their prayers so that they can say the deacon’s parts of the holy services.

In very practical terms, the restoration of the diaconate should be a vital concern and objective of all the faithful. Given the heavy demands on our priests, the ordination to the diaconate of four to seven pious laity in each parish would vivify not only our parishes and the faithful but would fill a vital missionary need. These deacons would have specific responsibilities within the broad spectrum of services that are integral to the diaconate so as to fulfil—on behalf of all the members of the Body of Christ – the Saviour’s command that we continue his diaconia on earth until the Second Coming. In addition to the liturgical function which is basic to their ministry, these deacons could, so to speak, specialise in education, music, philanthropic ministry to the sick and poor, and in the myriad other duties which devolve to the deacon, the absence of which diaconal responsibilities no single pastor can possibly fulfil. Since the administrative responsibility of the community has always been an essential part of the diaconal ministry–under the direction of the head of the community–those deacons with particular talent and experience in this area would be of immeasurable benefit to the heavy burden of the priest. With the assistance of several deacons in our parishes—who are also employed in the secular world for their income but want to offer more of their time to the Lord in specific obligations—the need of these men is served simultaneously with that of the community and of the priest.

Finally, that seven deacons were originally chosen by the Apostles is significant: in the Old Testament the number seven often represents the limited perfection of created reality, that reality which exists in a beauty and completeness so profound that it reflects the divine order, despite the limitations. While eight signifies completeness, perfection, seven has come to signify the highest level possible in this life, but is not in and of itself, the ultimate reality, the eighth day, the perfection of life eternal in the bosom of the Godhead. The diaconal function, therefore, is also limited, and in that sense it is distinct from and not synonymous with the holy priesthood, even if there may be some deacons eventually deemed worthy of that awesome and exalted office. Although all priests and bishops must be ordained to the diaconate first, the function of diaconia is a complete and vital function in and of itself; and even though it is integrally dependent upon the function of the priesthood, it is not a temporary resting stop to the priesthood. Functions in the Church are hierarchical, clearly set forth, and all are necessary for the well-being of the Body of Christ. This is seen most clearly in the diaconate.

The diaconate is, to be sure, ideally suited to those pious laity who are sustained and elevated by the beauty of the services, who love the “order of the Lord’s house;” to those who want to give selflessly of hemselves in philanthropy on behalf of the entire community. It is suited to those who, because of these things, understand how profoundly this service is necessary to their well-being; and which service, culminating at the Lord’s Table, makes the Saviour present in their lives as a means wherein one continuously transforms his life and raises it above the ignoble pursuits of this temporal existence. This is the reality of diaconal service, even if one has to attend to the other mundane, albeit necessary duties of life in the world. And in continuing Christ’s diaconia in the world through their service at the Holy Altar, to the members of the Body of Christ, and to the world, they have the Seraphic Orders who serve at their side, aiding, guiding and interceding for them.

[1] Dom Gregory Dix, The Shape of the Liturgy, Dacre Press, London, 1960 (excerpted).

[2] 2 Ephesians 1: 6.

[i] This would appear to be a variant practice. More usually, the deacon does indeed carry the diskos at the Great Entrance but only makes the first commemoration, of the hierarchy. All remaining commemorations are made by the priest or bishop, if present.

[ii] Today this tradition continues in the (Augmented) Litany of Fervent Supplication,

where the deacon may choose from a selection of additional petitions according to the particular needs of the parish and its people.