One of the foremost experts on the depths of the human spirit, St. Isaac the Syrian, says in his 41st homily: “The one who has come to a realization of his sin is higher than the one who raises the dead through prayer; whoever has been able to see his own self is higher than the one who has been granted the vision of angels.” It is for the purpose of self-knowledge that we will examine the matter we have stated in the title.

One of the foremost experts on the depths of the human spirit, St. Isaac the Syrian, says in his 41st homily: “The one who has come to a realization of his sin is higher than the one who raises the dead through prayer; whoever has been able to see his own self is higher than the one who has been granted the vision of angels.” It is for the purpose of self-knowledge that we will examine the matter we have stated in the title.

Pride, egotism, and vanity – to which we can add haughtiness, arrogance, and conceit – are all different varieties of one basic manifestation: “turning towards oneself.” Out of all these words, two have the most concrete meaning: vanity and pride. According to The Ladder, they are like youth and man, seed and bread, beginning and end.

The symptoms of vanity, this initial sin, are: intolerance of criticism, a thirst for praise, a search for easy paths, and a constant orientation toward others. What will they say? How will it appear? What will they think? Vanity sees an audience approaching from afar and makes the wrathful affectionate, the irresponsible serious, the distracted concentrated, gluttons temperate, and so on – all of this as long as there are observers around.

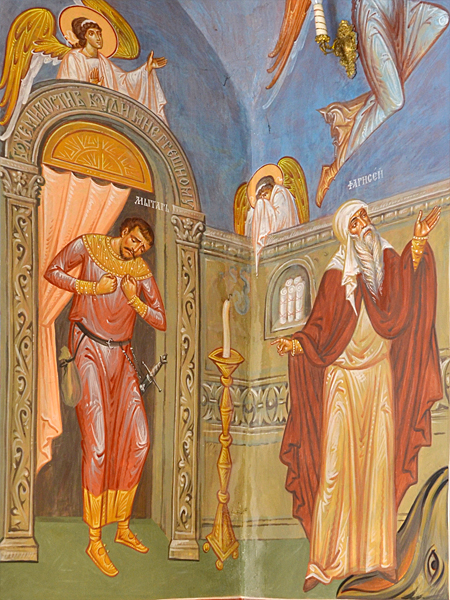

The same orientation towards an audience explains the sin of self-justification, which often creeps unnoticeably even into our confession: “I am no more sinful than the rest… only insignificant sins… I have not killed anyone or stolen anything.”

The demon of vanity is overjoyed, says St. John of the Ladder, seeing our virtues increase: the more success we have, the more food for vanity. “When I keep fast, I am vain; when I hide my spiritual labors, I am vain over my piety. If I dress pleasingly, I am vain; and if I put on old clothes, I become even vainer. If I begin to speak, I am consumed by vanity; if I keep silent, I become still vainer. No matter how you turn this prickly plant, it always has its thorns sticking upward.” As soon as a kind feeling or a sincere movement arises in a man’s heart, immediately there appears a vain, backward look at oneself. Thus these most precious movements of the soul disappear, melting like snow under the sun. They melt, which means they die; therefore, because of vanity, the best in us dies. Thus we kill ourselves with vanity and we replace a real, simple, and good life with phantoms.

Increasing vanity gives rise to pride.

Pride is supreme self-confidence and the rejection of all that is not of itself; it is a source of rage, cruelty, and malice; it is a refusal to accept God’s help; it is a “demonic stronghold.” It is an “iron curtain” between ourselves and God (Abba Pimen); it is an enmity towards God; it is the origin of all sin; and it is present in every sin. Every sin constitutes a willing yielding of oneself to one’s vice, a conscious flouting of God’s law, an audacity against God. “The one who is subject to pride is desperately in need of God, for no man can save such a one” (The Ladder).

Where does this vice come from? How does it begin? What does it feed on? Through what stages does it pass in its development? What are the characteristics by which one can recognize it?

Where does this vice come from? How does it begin? What does it feed on? Through what stages does it pass in its development? What are the characteristics by which one can recognize it?

The latter is particularly important, because a proud person usually does not see his sin. A wise Elder once counseled one of his monastics to shun pride. The latter, blinded by his intellect, replied: “Forgive me, Father, but there is absolutely no pride in me.” The wise Elder said to him: “There is no better proof of your pride, child, than such an answer!”

In any case, if a person finds it hard to ask forgiveness of others; if he is easily offended and mistrustful; and if he is rancorous and judgmental of others, then all of these are undoubtedly signs of pride.

In the Homily Against the Pagans of St. Athanasius the Great, there are the following words: “Men have fallen into self-desire, preferring to contemplate themselves rather than divinity.” This brief definition reveals the essence of pride. Man, for whom until now the center and the object of desire was God, has turned away from Him; he has fallen into “self-desire”; he has come to love himself more than God; and he has preferred self-contemplation to divine contemplation.

In our life, this turning towards “self-contemplation” and “self-desire” has become part of our nature and can often be seen in the mighty instinct for self-preservation, both in our earthly and our spiritual life.

Just as a cancerous growth often begins with a bruise or a continuous irritation of a certain spot, so the spiritual illness of pride often begins either with a sudden shock (for example, due to some calamity) or from a continuous massaging of one’s ego due to success, good fortune, or the constant exhibition of one’s talents, etc.

Often you are dealing with a so-called “temperamental” individual, who is passionate, talented, and easily fascinated. Such a person is like an erupting volcano, with his ceaseless activity preventing both God and men from getting near him. He is full of himself, totally absorbed in himself, and intoxicated with himself. He does not see or feel anything except his burning talent, from which he derives great enjoyment and satisfaction. One can hardly do anything with such people until they become played out, until the volcano becomes extinguished. Such is the danger of all talented and gifted people. Talent should be balanced by deep spirituality.

Otherwise, in reverse cases, in situations of great sorrow there is the same result: the person becomes totally absorbed in his misfortune; in his eyes the surrounding world becomes dull and dark; he cannot think or speak of anything except his sorrow; he wallows in it; and he finally holds on to it as the only thing left to him, as the only reason in life.

Often this turning towards oneself becomes developed in people who are quiet, submissive, and taciturn, whose personal life had been suppressed from childhood. This “suppressed subjectivity compensates itself by engendering a tendency towards egocentrism” (Jung, “Psychological types”) in the most diverse manifestations: quickness to take offence, mistrust, coquetry, seeking of attention, and even in the form of direct psychoses such as persecution mania, megalomania, etc.

Thus, a concentration upon oneself leads a person away from the world and from God; he becomes chipped off, so to speak, from the general tree trunk of the world and turns into a shaving curled around an empty spot.

The progression of the spiritual illness

Let us try to outline the major stages of the development of pride, from slight self-satisfaction to extreme spiritual darkness and total destruction.

At first it is seen as frequent attention to oneself, which is almost normal and accompanied by a good mood bordering on flippancy. A person is satisfied with himself, laughs a lot, whistles, hums, and snaps his fingers. He likes to appear original, to amuse others with paradox and wit; he exhibits unusual tastes and is capricious in food. He willingly gives advice and amicably interferes in the affairs of others; he unconsciously manifests his exclusive interest in himself with the following phrases (interrupting the conversation): “no, let me tell you,” or “no, I know a better story,” or “I have the habit of…,” or “I usually follow the rule of….”

At the same time, he is greatly dependent on the approval of others, depending on which he either blossoms or fades and becomes sour. In general, however, at this stage his mood remains fairly bright. This form of egocentrism is usually characteristic of youth, although it is sometimes seen in adults.

Such a person is lucky if at this stage he encounters serious concerns, especially for others (marriage, a family), a job, or some project. Or if he becomes entranced with the religious life and, attracted by the beauty of spiritual endeavour, realizes his spiritual poverty and becomes desirous of the aid of grace. If this does not occur, the illness progresses further.

There appears in him a sincere belief in his own superiority. Often this is expressed through irrepressible verbosity. What else is verbosity if not, on the one hand, an absence of modesty and, on the other hand, a delight in one’s own self? The egoistic nature of verbosity is not lessened by instances of discussion of serious topics; a proud person can easily hold forth on humility and silence; and he can glorify fasting and debate the merits of good works versus prayer.

Self-assurance quickly turns into a passion for ordering others around; such a person imposes his will upon others (but is intolerant of his own will being imposed upon); he takes charge of others’ attention, time, efforts, and becomes impudent and obnoxious. His affairs are important; the affairs of others are of little value. He tries to do everything and interferes in everything.

At this stage the proud person’s mood begins to spoil. In his aggressiveness, he naturally meets with opposition and rebuffs; he becomes irritable, stubborn, and peevish; he becomes certain that no one understands him, even his spiritual father; and his conflicts with the world increase and the proud person makes a final choice: “I” against others (but not yet against God).

The soul becomes dark and cold; it becomes the abode of arrogance, contempt, anger, and hate. The mind becomes obscured; the differentiation between good and evil becomes muddled, being replaced by the differentiation between “mine” and “not mine.” He escapes from all obedience; he is intolerable to all segments of society; his purpose is to propagate his own views, to vanquish and shame others; and he hungrily seeks fame, even notoriety, revenging himself upon the world for its lack of acknowledgment. If he is a monk, he leaves his monastery that has become intolerable to him and seeks his own paths. Occasionally this force of self-assertion is directed towards material acquisition: a career or social and political activity. Sometimes, if there is talent, it is directed towards creativity; in such a case, through pushiness, the proud person can even achieve some measure of success. On these same grounds schisms and heresies are created.

Finally, at the last stage, the person separates from God. If previously he sinned out of mischief and mutiny, he now allows himself everything: sin no longer bothers him, but becomes a habit. If he feels easy about anything at this stage, it is his easy relations with the demons and his easy access to dark paths. The state of the soul is dismal, hopeless, and totally isolated. But, at the same time, there is sincere conviction in the rightness of his path and a feeling of complete safety, despite the fact that he is being rushed on black wings to perdition.

In truth, such a state of mind does not differ greatly from madness.

At this stage, the proud person lives in a state of total isolation. Look at how he talks and argues: he either does not hear at all what others say to him, or hears only that which coincides with his own views. If something is said to him contrary to his opinions, he becomes angry, as though he were greatly offended, and viciously refutes everything. In those around him, he sees only those qualities that he himself had imposed upon them, so that even in his praises he remains proud, self-centered, and impervious to objectivity.

Characteristically, the most prevalent forms of psychological illness – megalomania and persecution mania – spring directly from “increased self-awareness” and are totally unthinkable in individuals who are humble, simple, and self-sacrificing. Even psychiatrists believe that paranoia is based upon an exaggerated awareness of one’s own self, a hostile attitude towards others, a loss of normal ability for adaptation, and an irrationality of beliefs. A classic paranoiac never criticizes himself: in his own eyes he is always right and is sharply dissatisfied with the people around him and the conditions of his life.

Here is a perfect illustration of the depth of St. John of the Ladder’s determination: “Pride is extreme poverty of the soul.”

A proud man suffers defeat on all fronts:

Psychologically: anguish, gloom, and barrenness.

Morally: solitude, the drying up of love, and anger.

Physiologically and pathologically: nervous illness and madness.

From a theological point of view: the death of the soul preceding physical death; the experience of hell while still in this life.

In conclusion, it is natural to pose this question: How should one struggle against this illness and oppose the destruction that threatens those who follow this path? The answer springs from the essence of the question. First of all, humility; then, obedience in increments to loved ones, elders, the laws of the world, objective truth, beauty, and to all that is good within us and around us; obedience to the law of God; and, finally, obedience to the Church, its rules, commandments, and mystical sacraments. Achieving this means following that which stands at the beginning of the Christian path: Whosoever wishes to follow Me, must renounce himself.

He must renounce himself and continue renouncing himself every day. Every day he must take upon himself his cross: the cross of enduring affronts, placing himself last, suffering sorrows and illnesses, silently accepting abuse, and offering total and unconditional obedience – immediate, voluntary, joyous, fearless, and constant obedience.

Then the path into the kingdom of peace and profoundest wisdom, which destroys all passions, shall become open to him.

Glory be to our God, Who opposes the proud and gives grace to the humble!