I feel more than slightly apprehensive, giving this talk in the background of a very theological theme. And so, you will forgive me, if my theological statements are untheological and if the rest is very different from what you may expect.

First of all, may I make a totally non-theological statement about the Holy Spirit? When we speak of the Trinity, for people as primitive as I am, we can imagine that the old image, given centuries ago, still holds, and we can develop it on one point. Speaking of the Trinity, trying to understand the relation there is between the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, some writers have said that we can compare God to the sun in the sky. In its mystery, the sun is unknowable as such. No one of us will ever be able to participate in the nature of the sun, but it becomes accessible to us in its light and warmth. The light is something which we perceive with our senses, by sight, and which reveals to us everything that surrounds us. We do not see the light as such, but it is in the light that things are revealed to us. The warmth of the sun is the way in which He pervades us, and in which we can become participants — to whatever degree is accessible to us — in the life of God.

Christ the Word is an objective revelation of God. The Spirit reaches us only within our experience, in the way in which the warmth of the sun pervades us and we become aware of it, and through it of something which is of God. This is a non-theological introduction to the subject.

As an illustration of this, I would like to give you an example of a contemporary of mine, who had discovered his faith in God through an encounter with Christ. But he puzzled and puzzled about the Holy Spirit. He did not understand. One day, he found himself on a bus. It was in Paris, around the theatre of the Odeon, and he was saying to himself or to God: ‘But what does the Holy Spirit do to us? How can I know that I have had some sort of contact with the Spirit of God?’ And of a sudden he felt he was, unexpectedly to himself, filled with a love of the creation and of the human beings that were surrounding him, in a way in which he had never known he could. And he realised that, at that moment, the Holy Spirit had come to him and made him partake, to the extent to which he could, in his immaturity perhaps, in Love Divine. At that moment, he knew something about the Holy Spirit: that the Holy Spirit was communicating Himself to him by communicating to him something which could not be invented or forced, even out of his human experience.

The Holy Spirit comes to us quietly; at times unexpectedly, at times as the result of a long longing. Some of you may have read a book called The Little Prince by Saint-Exupery. There is a passage in which the Little Prince meets a little fox. Both the Little Prince and the little fox are attracted to one another, but both are desperately shy. The little fox comes and sits down at a certain distance, but whenever the boy makes a movement towards it, it runs away. Then one day the little fox says to him something like: You know, we both long to come to one another, but we are shy and afraid. So when I come, don’t make the slightest move. Look askance, so that I may imagine that you have not noticed my presence. And, not being afraid of being watched, I will come a little nearer than the day before, but don’t turn to me, because I will be afraid and run away. And then, another thing,’ he said, ‘I long to come close to you. And so, let us fix a time when you will come, because then — oh, a good hour before the time — I will know that you will be coming. I’ll come myself and wait. And I shall be filled with this expectation of the moment when you will appear. And then you will sit down and, as I said, pay no attention to me, and allow me to come nearer, and nearer, and nearer.’ This image of the little fox is something that, to me, resembles very much the way in which we relate to the Holy Spirit. Christ comes to us, proclaiming the truth. He is the Truth; He is the One who Is. He is a revelation, an unveiling. The Holy Spirit, in this sense, is not a revelation. He is the one who makes the revelation possible, by making us commune with what is the essence of this revelation: the closeness and the knowledge of God.

If we turn to what we hear in the Gospel about the Holy Spirit, I would like to attract your attention to one passage — to a word rather than a passage — that we repeat time and time again in our prayer: the Comforter. ‘Comforter” is the English translation of the word. When we look at the various languages into which it has been translated from the original, I think we can see a variety of facets in the event. First of all, the Holy Spirit, whom the Lord Jesus Christ sends us, is the one who consoles us for our loss of Christ. I am speaking of the loss of Christ, because each of us believes in Christ, each of us has had an experience of His closeness, His presence. Each of us has had, through His teaching, an experience which He conveys to us in word and in person. But, with the Crucifixion, the death of Christ and the Resurrection and Ascension, He is not present as He was present to His disciples, and He is not present in the way in which He will be present to us when all things will be fulfilled. You remember, probably, the words of Saint Paul, when he says: As long as I am in the flesh, I am separated from Christ. And yet — Christ is my life. And we are all, to a lesser degree than Paul was, of course, in the same kind of situation. On the one hand, Christ is our life; on the other hand, we are still separated from Him. We all long to be with Him, but we cannot go beyond a certain point of closeness. And Saint Paul points it out, when he says that, as long as he lives in the flesh, he is separated from Christ, and he longs for death to come. Not as an end of his earthly life, but as the moment when a veil will be torn apart and, as he puts it, he will know as he is known. He will see face to face what he can see yet only as shadows and images mirrored.

The Holy Spirit reveals Himself to us as our Consoler. In the sense that Christ has promised to send Him to us, He comes to us. He gives us an incipient participation in a closeness of communion with Christ, and through Christ, in Christ, with the Father. So that this is our first experience. His closeness to us consoles us for the fact that we long to meet Christ face to face, to commune with the Father in a way unutterable to us.

But the word goes beyond this. He is not only the one who comforts us; He is the one who gives us strength; strength to live in this orphaned situation in which, on the one hand, we belong to God wholeheartedly, sincerely, heroically at times, and on the other hand live in a world that has fallen away from God and in which we have a function to fulfil. He is the one who gives us strength to live in the world which at times denies everything we long for, which stands between us and our fulfilment by temptation, by beguilement.

At the same time, there is a third meaning in the word. He is not only the Consoler. He is not only the one who gives us strength to face life, in the faith and yet in the partial absence of Christ. He gives us the exulting joy of being with Christ already in this world, because, although our communion with Christ is imperfect, although it is not all-embracing, although we do not know Him as He knows us, we do know Him. And this is a miracle that we could not appreciate if we were born, as it were, in a believing family and if we had been given our faith together with our birth. But those of us who were unbelievers, the millions who believed not and have discovered, know the exulting joy of this discovery of God in Christ and through Him, of the fatherhood of God’s own Father. So that, in the Holy Spirit, we have consolation because we are orphans. We are sent into the world to conquer it for God. And in the process, at moments, we are given a sense of incredible closeness, and we can be astounded and rejoice in the way in which the young man whom I mentioned in the beginning rejoiced, having been filled, in an unutterable manner, with a love he did not know could exist; not only for humanity, not only for every concrete human person, but for the whole of creation.

We are told by Christ that He will send the Spirit to us, who will lead us into all truth. ‘All truth’ is not an intellectual situation. It is not the knowledge of the mind; it is an experiential knowledge. The truth (in Russian istina) is what is: I am He who is. And the knowledge of the truth can only be possessed in communion with Him who is. In a strange way, we have lost through the centuries this certainty that this is what the truth is. It is God Himself; it is the absolute Reality. Pavel Florensky, speaking of the truth, says: ‘Istina — eto Estina’ — the Truth is what is!’ ‘I AM’. And strangely enough, because we have moved knowledge of the truth from this existential experience onto an intellectual level, we feel that we must fight for the truth and defend it, forgetting that the Truth cannot be destroyed by any created power. The Greek word aletheia means ‘what cannot be washed away’, annihilated, even by the waters of the River of Oblivion. Nothing can do it!

If we continue to dwell on words, we could remember that the words verity, veritas, Wahrheit, derive from a Latin word meaning ‘to defend’, not ‘to be defended’. The Truth can defend us against everything, and it does not need us to defend it. This is a very important point with regard to our mission in the world, because it means that we are sent to proclaim it and reveal it, but not to defend it in argument. We cannot defend the Truth by argument. We can present another facet of things, which people can accept or not, but we cannot always defend it in the way it should be defended. I remember when I was young and began to do youth work, my father saying to me: ‘Proclaim the truth and be to people a vision of it, however dim, but do not try to convert anyone by argument, because, if you prove to be more intelligent, more well-read than another person, you will be able to defeat the other person, but you will not have changed his life. And I remember an occasion, a case in the comparatively recent history of the Russian Church in Stalin’s time. A young man called Evgraff Doulouman, who was a student at university, was looking for digs. He found a room in the house of the local parish priest. The priest was mature, ageing, with a deep and tragic experience of life: of the beginning of the Revolution and of the persecution that followed. The young man was full of his atheistic convictions, and he decided to convert the priest to what he believed to be the truth, and they engaged in conversation and discussion. The priest was an old and wise man. He did not argue point by point, but unfolded before the young man the truth as he knew it. The young man was not mature enough to go through the experience that was offered him, and he made it into an intellectual world-outlook that defeated, completely annihilated, his atheistic vision. Having been dialectically defeated, he embraced the Christian faith, asked for baptism, went to study theology in Zagorsk, was brilliant as a student, was ordained deacon and priest and was sent to Samara, I think, to a parish. It was expected that he would be a brilliant missionary, taking into account the way he had moved from refined, deep atheism into a powerful sense of Christianity. When he was in the parish, this young man discovered — in the celebration of the Liturgy, in the sacraments, in his pastoral work — that he could present the Christian truth in words, but he did not believe it all in his inner self. After a while, he renounced the Church and became an active agent of atheist propaganda. I give you this example to underline the fact that it is not in the refinement of argument in debate that one conveys one’s faith.

In the course of the whole history of Christianity, you meet people who are filled with the Holy Spirit, and whose life, whose person, whose words, in their simplicity reached others, hit them at the very core of their being and brought to life a knowledge of the divine that had been dormant. It has been for many as though the knowledge of God was like Lazarus: dead, lying in his grave, who suddenly heard a voice saying: ‘Lazarus, come out!’ And the knowledge of God, an experience that was conveyed by having heard God speak to him, made all the difference. And so, when we speak of the Holy Spirit as being the Spirit of truth, it is not the spirit of formal theological discourse or of any formal thing divorced from the inner experience. Unless it is sustained by this inner experience, it may be a convincing argument but it will not be a power that can transfigure the life of another person.

We are sent into the world to proclaim Christ, but we are not sent into the world to argue about Him. In 1943, C. S. Lewis gave a series of addresses on the English wireless, and in one of them he asks: “What is the difference between the believer that has become alive in God and any other human?’ And he says: The difference can be compared to that which there is between a statue and a living person. A statue may be of supreme beauty, but it is nothing but stone or wood. It can be looked at and admired. It can send us a message of beauty, but not of communion. This beauty will be communion with something earthly, created, but not beyond. Something must happen that will make it of the ‘beyond’. A human being may be infinitely less beautiful than a statue, but it is alive.’ And C. S. Lewis says: “When someone meets one of those statues that have become a living person, he should stop and say: “Look, this statue has come to life!” ‘ This is a challenge to each of us, because we may be satisfactory statues, but are we the kind of people whom others meet, look at and discover that there is life there and not only a shape?

It is very important for us to realise that our message to the world is not a world-outlook. It is a revelation of the presence of the Holy Spirit and of Christ. The Church is a mysterious Body, because the Church is the presence, in the midst of the fallen world, of the fullness of the divine Presence. The first member of the Church is He whom Saint Paul calls the Man Jesus Christ. He is one of us, as well as being, if I may put it that way, one of Them. He is not only One of the Trinity; He is one of humanity. Looking at Him, we can see what it means to be both totally man, human, and totally and perfectly divine. Since the Ascension and the Feast of Pentecost, the Holy Spirit has indwelt the Church totally, filled it with His presence. In the Spirit and in Christ, the whole Trinity is present in the Church. Are we Christians, Orthodox Christians, aware of this? Or is the Church a human body that looks Godward, that believes in God, that has evolved a very elaborate theology, but whose members are not limbs of Christ — as Father Sergei Bulgakov puts it: ‘an extension of the Incarnation’? Are we ‘an extension of the Incarnation’? Does anyone, meeting us, stop a minute and say: ‘In this person, there is something I have never met before. Here is a human shape, but there is something beyond it.’

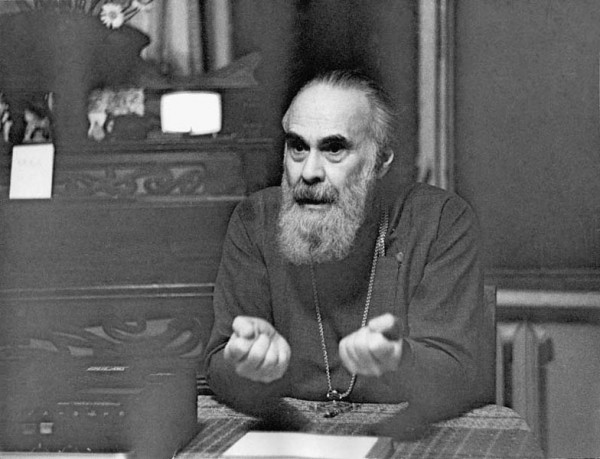

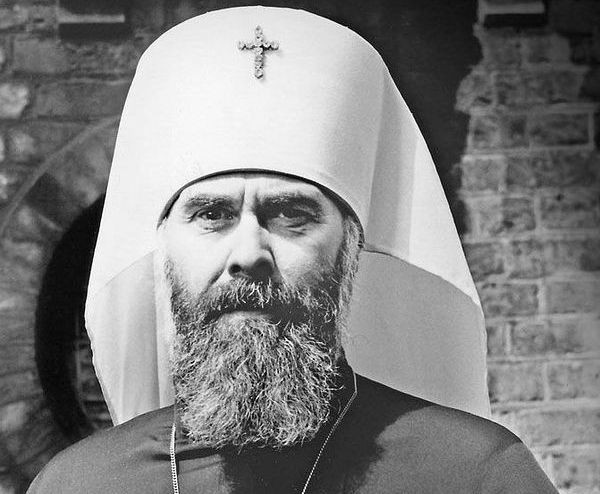

I think I have mentioned a personal example which I will dare mention again. I came once to the church that became my parish for years in Paris. I aimed at being present at the Vigil, but for one reason or another I was late. The service was over. It had taken place in an underground garage, that led to ground level up a wooden staircase. I entered, and saw that everything was over. Only, there was a man coming up the stairs. It was a monk, in monastic garb, and when I looked at him I felt that I had never in my life met such total inwardness, such serenity, such peace and depth. I did not know who he was. I came up to him and said: ‘I do not know who you are, but would you become my spiritual father?’ This is a sort of central experience I had of a person in whom I saw something I had never seen to that extent: this total inwardness in the abiding presence of God, the Spirit at work, and the Incarnation in him. Years later, I received a little note from him, saying: ‘I have experienced the mystery of contemplative silence. I can now die.’ And three days later, he died. This, to me, was an example of what a Christian can be. He was not ‘impressive’ in any respect. He was not a man of superior education or of an outward holiness, but in him I could see the Incarnation and the presence of the Spirit.

When we look around, do you realise the kind of world in which we live? Bishop Basil must have talked to you about the presence of the Holy Spirit in the created world. At the moment of creation, the Holy Spirit was hovering over the newly-created world. This newly-created world, in translation, is called ‘chaos’. When we think of chaos nowadays, we think of destruction, the chaos that followed the bombing of Dresden. But chaos is something much more essential and deeper. Chaos is the sum-total of all the existing possibilities that have not yet found a shape and blossomed out. The Holy Spirit was breathing over the chaos, over all the possibilities of a world that had been called into being and had no shape yet. By breathing over this chaos, the Holy Spirit was bringing to life all its possibilities, and everything that was hidden as the possible began to emerge as reality, as you can see in the beginning of Genesis. But God did not force the shapes. He initiated the possibility for the creation to become itself more and more; to expand in depth, and in width, and in every respect

Things changed with the Fall. But what had been given first was never taken away; the created world is still that world which God created. If it is distorted, it is not because it has turned away from God, but because its guide, man, has turned away from God, has lost his way and has proved incapable of helping this chaos to become the perfect cosmos: beauty in form, in line and life, so that the world in which we live is the world which, in itself, is pure of stain except for the distortion that we have created in it. When we look at the surrounding world, we must be aware that everything that is monstrous, frightening, ugly and distorted in it is our doing. To apply to the generality a phrase that was spoken in a particular situation, one of the Fathers says: “We must remember that what we call the sins of the flesh are the sins that the spirit inflicts on the flesh. The flesh is pure.’ We make it a victim of sin. Our body says: ‘I am hungry.’ Our imagination says: ‘I want to delight in such-and-such foods.’ The natural situation of the created world is that of a victim of the human fall, of our being separated from God, of our being unable to restore, even in a small patch of land, the purity, the wholeness and the harmony that belong to it by right. This we must remember. With what veneration must we look at the cosmos and everything that is the material world around us, and what broken-heartedness we must feel when we see it distorted, broken, ugly and monstrous at times.

Again, when we turn to God, to God’s revelation and the creation of man — the Lord God breathed His own breath into man: that is the original human, the anthropos, the chelovek, and man, the total man, has remained filled with the Spirit of God. We must remember this: it is not our Christian, our Orthodox, privilege to be such. All human beings are such. Sinful, yes, but basically such. And so, when we look round at all human beings, we have no right to see good in some and evil in others. We must see victims of the human fall in one and the victory of Christ in the Spirit in the other. The saints are examples of this victory. To them, to the extent to which it is possible in a world which has not yet come to the parousia, to its end in Christ’s victory, we find, incipiently or still-surviving, true humanity. And this we must remember when we deal with whomever we deal with. Some people are ‘evil’, yes. But why are they? Have we given them newness of life by being a revelation of Christ and a gift of the Holy Spirit? It is easy, perhaps, at times to be compassionate to a person in error, but how easily do we condemn the error from the height of what we imagine to be the truth as we know it!

I have paid some attention, in the course of the last seventy years or so, to the beliefs of men, to the religions of the world. What strikes me more and more is that, however different they are from the faith of Christianity, they are all a distortion of the truth; not a straight lie against it, except for some who have chosen to be servants of Satan and not servants of Christ.

I would like to keep you a little longer than I intended: my forty-five minutes are just over. If you will allow me ten more minutes, I will let you free.

Many years ago, I had a conversation with Vladimir Lossky about oriental religions. He was absolutely in denial of any knowledge, any true knowledge of God, in them. I did not dare argue with a theologian of such magnitude, but what courage could not achieve, I thought cunning might. As we lived across the street from one another, I went home and copied eight passages from the Upanishads, the most ancient Indian writings, went back to Lossky and said: “Vladimir Nikolayevich, I have been reading the Fathers, and I always take down the passages that strike me particularly. I always put down the name of the author, but alas, with these eight quotations I cannot find the author’s name. Could you identify them for me?’ He looked and said: ‘Oh, yes!’, and within a minute and a half he had put eight names of the greatest Fathers of the Church under the quotations from the Upanishads. And then cunning revealed itself in false humility, and I said to him: ‘I’m afraid I have deceived you. These are from the Upanishads.’ He looked at me and said: ‘Really? Then I must read them.’ And that was the beginning of a change of mind in him with regard to the statements of other religions.

Many years ago, in 1961, I was part of the first Russian delegation to the World Council of Churches in Delhi. Among a number of us, there was a man called Father Ioann Wendland, who later became a bishop in America and in Germany. He had been a secret priest in Siberia while doing geological research during the Stalin period. We decided to go to a pagan place of worship, to see and to try to understand. We arrived there. At the door, we had to take our shoes off, which we obligingly did, and we were about to leave them there when the warden came up to us and said: ‘Oh no, sir, you do not leave your shoes here. They are new and good, and would be stolen. I’ll put them in my office.’ So our shoes went into the office and we went into the place of worship. It was a round place of worship, divided into ten or twelve sections, and in each of them there was what we would call a pagan denomination, worshipping in its own way. We sat one after the other in the ten or twelve compartments, at the back, using our rosaries and praying the Jesus Prayer, trying to commune with God and seeing if we could commune with the people there. We both came out of it with the certainty that, whatever they called their god — whether it was the god-elephant or the god-monkey or another — they were praying to the only one God there is. And we had communed in prayer with them all, in spite of the fact that, on the surface, they had been praying pagan prayers to idols. That also made me think.

I will end your torment with one more thing. What I have said should make us much more understanding and attentive in our attitude to unbelievers. Not those who are empty of belief but those who are actively godless. I will give you one example, which some of you must have heard from me, because I always repeat myself. The example is this: I was coming down the steps of the Hotel Ukrainia a number of years ago. I was wearing my cassock, as I always do. A young man came up to me and said: ‘I am an officer in the Soviet Army. You are, I presume, a believer, dressed as you are.’ I said: Yes.’ Well, I am an unbeliever. Bezbozhnik (I am godless).’ I said: That’s your loss.’ He said: ‘And why should I turn to God? What have I got in common with Him?’ I said: ‘Do you believe in anything at all?’ Yes,’ he said, ‘I believe in man and in humanity.’ I said: ‘In that, you and God share the same faith. Start at that point.’ And, I think, more often than we do, we should be aware that there is no-one who lives without a faith, without believing in something. And more often than not, we may discover that God believes in the same. Only better, deeper, more perfectly, but that this person who fears that there is nothing between God and him has something in common with Him. At this point, we may remember the passage of the Gospel in which Christ says to Nicodemus: The Spirit blows where It chooses, and no-one knows where It comes from and where It goes.

We must be infinitely reverent when we look at the world that surrounds us, which we have distorted and which suffers like a martyr under the result of human sin, and remains pure, so pure that God could become man and put on flesh; a flesh He inherited not only from the personal saintliness of the Mother of God but from the fact that she was the heir of all the saintliness of thousands of years of human life in history. We must remember that all humans are possessed of this breath of life which is God’s breath and God’s life, however distorted it may be. We must remember, as I have said, that the Spirit blows where It chooses. Without this precondition of the way in which the world, mankind, relates to God, no-one — no one of us and no-one in the world — could discover God. It is the Spirit that reaches us and that kindles in us life eternal. So, when we speak of being sent into the world, we must remember that we are unworthy messengers of a message that may be received by the created world around us, and by the humankind around us, better than we are capable of proclaiming it.

How often it happens that words of truth are said that do not reach the congregation that is there, but reach someone who by accident, or by an act of divine Providence, has entered the church. We must remember this. And go into the world, not to proclaim a theoretical theology of the mind but to grow into the life of Christ, to open ourselves to the action of the Holy Spirit, to believe that the Holy Spirit is active in the created world which is dear to God. Dear to God, because the Body of Christ belongs to this created world through the Incarnation, and to mankind — to everyone.