I really like the Roman Bishop’s official title: “the servant of the servant of God.” Regardless of how it is realized in the life of any particular pontiff, the title itself is very much Christ-centric and conveys the correct idea: a priest or a bishop receives his authority from Christ, and it is His, Christ’s, authority, not the priest’s. So, in order to find out how a priest is to exercise his authority, we must look at how Christ exercised His authority and learn from His example.

“For to us a child is born, to us a son is given; and the government will be upon his shoulder…” (Isa. 9:6) What is “the government upon shoulders”? Is it some kind of epaulettes or shoulder boards—the usual symbols of government? Not quite. He was “bearing his own cross” (John 19:17), “He bore the sin of many” (Isa. 53:12). Is this the image of a general in epaulettes?—“He had no form or comeliness that we should look at Him, and no beauty that we should desire Him. He was despised and rejected by men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief; and as one from whom men hide their faces He was despised, and we esteemed Him not” (Isa. 53:2, 3).

A secular leader acts on the following principle: “Come to me, all ye to whom I have not yet ordered anything, and I will give you duties.” Christ says: “Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest” (Matt. 11:28).

Who is the greatest in a secular kingdom?—He whose hat is the tallest and servants are many. But when Christ was asked who was the greatest in the kingdom of heaven, “calling to him a child, he put him in the midst of them…” (Matt. 18:1, 2).

“And he sat down and called the twelve; and he said to them, ‘If anyone would be first, he must be last of all and servant of all’” (Mark 9:35).

“If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet” (John 13:14).

Verses such as these are plentiful; all of them point to a very important quality of Christ’s headship—it is quite different from that of secular rulers and leaders. <…>

Although we call ourselves slaves and servants of Christ, He calls us His friends (John 15:15) and lays down His life for us (13). This means that our slavery is not that of a captive who is bound by violence, but that of a loving heart which is captured by Christ’s love.

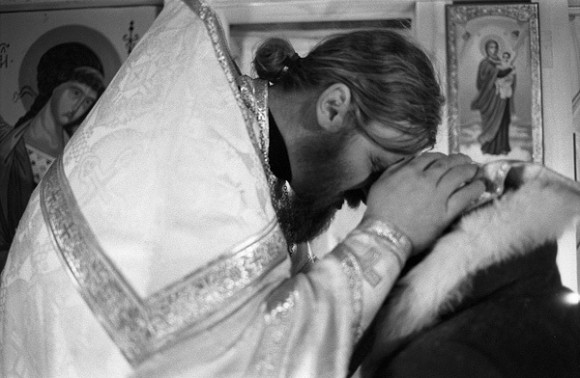

And it is the same with a priest: he is to serve his flock rather than expect them to become his servants, to sacrifice himself for his flock rather than demand sacrifices from them, to help carry their burdens rather than place on them burdens too difficult to bear, and to unite in love rather than in administrative obedience. This may be an ideal unreachable in its fullness in our fallen state, but shouldn’t it be at least the direction to which the inner compass of every priest points?