In our previous article about the importance of reading the Scriptures, we mentioned how a child’s words, providentially overheard by Augustine of Hippo, led to his conversion as he took up and read the Scriptures. “Take up and read” (“tolle, lege”, the words actually heard by the great North African teacher) should continue to resonate in our hearts too. If our lives are to bear fruit for Christ, we also need to take up and read the Bible, and make this a part of our daily life. The question is: how do we read the Scriptures? What things should we bring to our reading? I would mention four things.

1. The first thing we bring to our reading is a heart of humility and prayer, asking God to teach us through what we read. That is, we must read the Scriptures on our knees (spiritually speaking), or not at all. The most dangerous thing in the world is the read the Bible with a proud and unteachable spirit. God will not touch or teach with the person who approaches His Word in this way. “The Lord regards the lowly, but the haughty He knows from afar” (Ps. 139:6). Rather, “this is the man to whom I look: he that is humble and contrite in spirit and trembles at My Word (Is. 66:2).

To be lowly and humble involves a willingness to be corrected. We all come from a secular culture, and we have absorbed many things from it, some of them true, some of them false. Because Scripture is not only the word of men, but also the Word of God, it stands apart from all the other literature of the world, in that its teachings are always true and reliable. Thus, when we read the Scripture we can expect some of our cherished beliefs to be blessed and confirmed, and some of them to be contradicted. Humility means the willingness not only to be confirmed when we are right, but also contradicted when we are wrong. As St. Augustine is reported to have once said, “If you only believe the parts of the Gospel you like, it is not the Gospel you believe in, but yourself.”

This faith in the reliability of Scripture is not Protestant fundamentalism (as some have imagined), but historic Orthodoxy. To quote St. Augustine more fully, “I have learned to hold those books alone of the Scriptures that are now called canonical in such reverence and honour that I do most firmly believe that none of their authors has erred in anything that he has written therein. If I find anything in those writings which seems to be contrary to the truth, I presume that either the codex is inaccurate, or the translator has not followed what was said, or I have not properly understood it.” We see here the mind of all the Fathers, east and west, and their saving willingness to be corrected from the Bible. As children of the Fathers, their willingness must be ours as well.

2. As well as imitating the humility of the Fathers, we read the Scriptures as those who have listened to their sermons and been instructed by them. We read the Bible, as it were, sitting in their lap, interpreting it in ways consistent with their interpretations. This is because before the apostles ever set pen to paper and wrote the New Testament, they also taught their churches through the living word, and these words were kept in those churches as oral tradition. The Fathers represent and carry this apostolic Tradition, and so Scripture can only be interpreted in ways consistent with what the Fathers have preserved.

This does not mean that we are to become patristic fundamentalists, so that for us exegesis becomes archaeology, a mere wooden repetition of what the Fathers have said. We are allowed the same freedom that they enjoyed. But it does mean that their basic approach is paradigmatic for us, and their basic conclusions authoritative. For example, if the patristic consensus about the New Testament is that it teaches that Jesus is divine, then any other conclusion is out of bounds. We cannot follow the creative heretics of the so-called “Jesus Seminar” in their Christological conclusions about the New Testament. We have sat and still sit at the feet of the Fathers.

3. Consistent with this patristic approach, we read the Old Testament to find Christ there. That is, the Old Testament, as well as the New Testament, points towards Jesus Christ, His Cross, His Resurrection, and His Church. This is how the apostles interpreted the Old Testament, and it points the way for us also. The Kingdom of God proclaimed by the prophets does not find its fulfillment in Zionism in this age, but in the preaching of the Gospel and the salvation offered the whole world by Christ. This means that we read the Old Testament differently from the Jews. Jews believe the ultimate fulfillment of the prophecies lies with the exaltation of the Jewish race, with a reestablished Temple and a triumphant nationalism. We assert that the Old Covenant finds its fulfillment in the Body of Christ, in the Church of God in which there is neither circumcision nor uncircumcision, but a new creation (Gal. 6:15), and in a salvation which transcends literal altars, and national boundaries, and the distinction between Jew and Gentile. As St. Justin the Philosopher said in his debates with his Jewish friend Trypho, Moses and the Prophets now belong to us.

4. Finally, we read the Scriptures with all our powers, including that of the mind. Reading in humility and hoping to be taught by God does not excuse us from sweat or scholarship. Scholarship is not to be despised, but all of its useful tools must be utilized, including Bible atlases, concordances, inter-linears, word studies, commentaries, scholarly journals, lexicons. The Fathers themselves prized such scholarship (that was one of the reasons Origen got a lot of fan mail), and they bequeath this love of learning to us also. The Lord tells us to love the Lord our God not only with all our heart, soul and strength, but also with all our mind (Mk. 12:30). Part of humility is the recognition that we need all the help we can get. God will bless us and enlighten us, but not if we use supposed piety as an excuse for laziness. Study involves work.

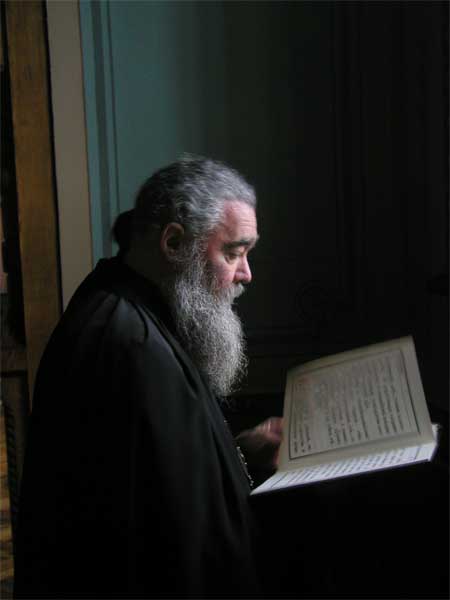

In many icons where a bishop is portrayed, he is portrayed as holding a Gospel. It is not accidental that our leaders are portrayed as holding this Book. We are “people of the Book”, a people for whom loving Jesus also means loving the Scriptures which His providence has given to the Church. Like St. Augustine and all his other episcopal colleagues, we also are called to take up the Book and read.