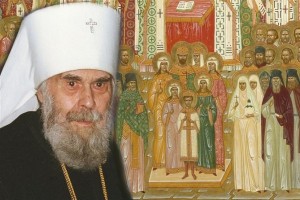

With the blessing of His Holiness, the late Patriarch Alexei II of Moscow and All Russia, the memory of the New Martyrs of Butovo is celebrated on the fourth Saturday after Pascha. The following essay by Dr. Maria Degtiareva of the Department of Theology at Perm State University was written in 2010.

The first time I found myself here was four years ago. I did not come on my own, although I had heard about this place more than once, even seeing some annotated photographs in the newspaper: Patriarch Alexei serving on the firing range beside the familiar faces of priests, rectors of churches in Moscow.

But my impression was then limited to certain scraps of sentences: “Butovo, place of mass executions,” “stone laying,” and something about a “memorial cross.”

I was taken to Butovo by an acquaintance, a nun from one of the Moscow convents. With her, we were ten people. For Matushka this is a special place: on this piece of land, in one of the common graves, lays her father. No, he was not a priest. He was an ordinary office worker. He just happened to be among those who landed on the “black list”; he was arrested and never released from prison. Only many years later, when the archives were declassified, was his fate clarified and his place of execution identified. Her childhood memories about the events surrounding this have retained a horrible scene: when, after the arrest of her father, the “black car” [1] came for the rest of them, the neighbors violated the unwritten rule of silence by making a scene and not giving them up. At first they went into hiding, not having a home of their own. Thanks to this, they lived. And now we are going to Butovo.

The six-hectare “specially protected area”

I had had the impression that it was somewhere very far away, but the entire journey from central Moscow took not much longer than an hour. For Moscow, that is no distance at all. It is practically next-door, in a grove just off the highway. Now that the city has grown, there is a new residential complex not far away: grey serial houses in which life goes on as usual, with children playing in the yards. Even in earlier times, back in the thirties, there was a dacha settlement here, not that far away. Families vacationed here, going sunbathing and wandering through the woods. Given, one had to walk carefully and cautiously, knowing that it was better not to walk near the long plank fence. Not because the gunfire was deafening, but because the place itself emitted a heavy, unfriendly smell.

Officially, it was known that light artillery was periodically fired in this specially protected area of the NKVD-KGB, a space of only about six hectares. Nonetheless, this was a strange place. In the thirties, residents of the dacha settlement would see how, at intervals of approximately once every two days, a fairly spacious covered car bearing the inscription “bread” would approach the firing range. People were perplexed: why was bread being brought in such large quantities to a military facility located on a small territory? By the mid-thirties this place had already acquired a firmly established “reputation”: one kept quiet about it. Only years later did the old dacha owners tell about how one of the neighbors happened to see how at night groups of half-dressed people were led under guard through the forest next to the range – and then shots were fired. It was also said that there were several cases of residents of the settlement also disappearing, possibly because they had witnessed something they should not have.

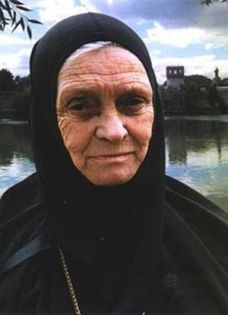

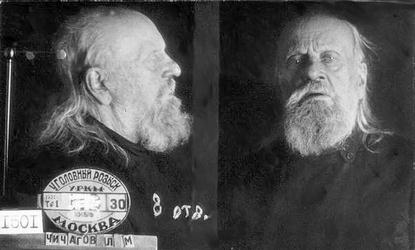

Now here is that very fence. It differs from an ordinary fence only in that several rows of barbed wire have been placed on top. Varvara Vasilevna Chichagova-Chernaya – the well-known scientist, academician, and granddaughter of the now-glorified Metropolitan Seraphim (Chichagov) – saw just the same thing in 1994. [2]

The circumstances compelling her to come here were as follows: many years ago, in 1937, when she was still a student, a misfortune took place in her family: her grandfather, Vladyka Seraphim, was arrested while alone at the family dacha in Udelnaya. The people taking him away were nervous, so they did everything they could not to draw the attention of outsiders. An ambulance came to the house and, a few minutes later, the ailing eighty-two-year elder was carried out on a stretcher and taken away, as if it had been a routine call. Attempts to discover at least something of his whereabouts led nowhere: the same answer awaited them in every hospital and prison in Moscow: “Chichagov is not listed.” Varvara Vasilevna’s search for her grandfather was postponed for more than half a century.

Then one day, when she had already become a scientist of world renown and the director of a major scientific institute, on the second day after Nativity, the telephone rang in her apartment. A question was posed by an unfamiliar female voice:

“Do you know where your grandfather is buried?”

“No, I don’t.”

“In Butovo, in the KGB’s firing range.”

It turned out that getting into the range during the winter was impossible: it was closed. Nonetheless, Varvara Vasilevna went there immediately in search. The first time she did not get in. So there she stood before the tall, impenetrable fence with the barbed wire…

“The Russian Golgotha”

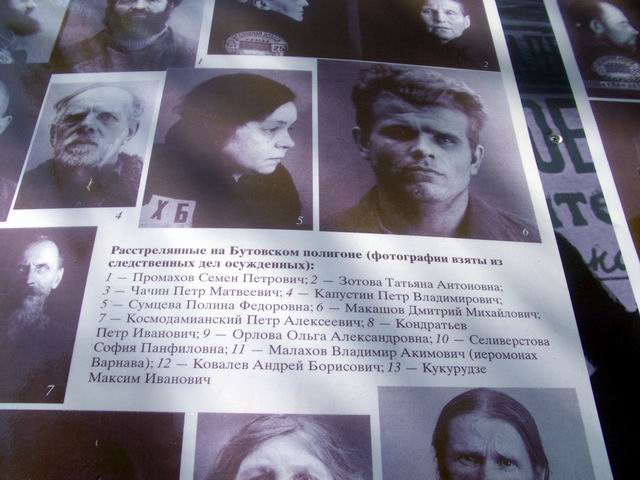

Through the efforts of a very small group of people with access to archival affairs, it became possible to reconstruct the history of this place. These people are amazing: two women working with documents and a few relatives of the victims. Xenia Fedorovna Lyubimova compiled a card index of those shot and buried in the Butovo firing range. At present, not all of the materials have been processed. The creation of the card index required time, patience, and, quite simply, physical strength. It must be said that the memory of the women working in these investigative matters is extraordinary. The following scene, for instance, took place in our presence: a Muscovite who had come to Butovo for the first time, not hitherto knowing anything about the fate of her relative and only guessing that he might be here, timidly gave his last name and date of arrest. In response she heard, in a firm voice, his first name, patronymic, and a confirmation: “Yes, he is one of ours.”

It was gradually revealed, layer-by-layer, what this protected area of “military purpose” actually represented. Formerly the estate of the merchant and manufacturing Zimin family, with a once well-tended park and a stud farm, it was voluntarily handed over by the owners to the new authorities after the revolution. In the twenties it was turned into an agricultural colony of the OGPU. [3] But in the beginning of 1934, prisoners from the former St. Catherine’s Monastery, where a prison had existed since 1931, began to be brought here by cart. [4] The barbed wire fence made its first appearance. Sentries were posted here and there… And then the shooting started, sometimes going on for several hours at a time. At first, the dacha residents did not attribute any particular significance to this: a firing range is a firing range. Suspicions arose later, when people returning to their houses late at night began to see the “black cars,” in the form of tightly covered vans. Sometimes there were several at a time. It would happen that distant screams would be heard. But times were such that people feared even sharing their suppositions with one another.

By now it is known that the former special zone of the NKVD-KGB in Butovo is the largest mass grave of victims of political repression in the Moscow area. Among those executed were a great many clergy, including six bishops, as well as monastics and simple believers, laypeople who assisted in churches. Over several years, by decrees of the Council and Synod of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church, 230 of them were glorified among the saints.

The peak of executions came during the “Yezhov era.” [5] In one year, from July 1937 to August 1938, there were 20,765 executions on the firing range. Of them, approximately 1,000 (based on investigative materials) suffered specifically for their fidelity to the Church and to faith.

But it seems that trouble had to be faced even in death. After all, the Lord Himself was crucified between thieves. Here, in the unmarked grave pits, lie the remains of both saints and persecutors of faith, of both victims and their torturers – side by side, one next to the other. This is a difficult thing to write about: the firing “brigades” accomplished their missions while drunk on vodka, so horrible was their work. And among the assignments of some of these “brigades,” as they say, was the “liquidation” of those they had replaced. In such manner, this place, where significant people were executed, was covered up, recorded in such a way that none would be the wiser.

Several years ago, the current rector of the Church of the New Martyrs in Butovo, Fr. Kirill Kaleda (grandson of the Hieromartyr Vladimir Ambartsumov) [6] made an attempt to uncover a small fragment of an execution pit, using every precautionary measure with the invited help of experienced anthropologists. It then became clear that finding relics, for which they had had a modest hope, was impossible. In one ten-meter square, nearly 150 human remains were discovered. People lay five layers deep – which means that the killed and wounded had landed on the dead.

With the help of aerial photography, the topography of the ditches has been established: there were more than ten. There are enormous trenches, sixty to seventy meters wide and four to five meters deep, in the shape of “pi” and “lambda.” Buried in them are people of sixty nationalities and of a wide range of socio-political views and cultural backgrounds. Butovo has become one of the most horrible testimonies to the apostasy of the twenties and thirties – and, simultaneously, one of the most significant symbols of fidelity to Christ.

During that first trip to Butovo, I caught myself thinking that it was terrible to walk on this ground. There is literally no free space in it: the entire place is a “common grave.” When no space was left in the fenced-in square, the shooting of small groups of prisoners was carried out in the nearby woods. And yet, regardless of the numbness that set in here at first – due to the exceptional severity, scale, and proximity of this tragedy – a different feeling gradually arose. I could not put my finger on where and when I had had this same feeling. Only later did I remember: it was just the same in Rome, on the Appian Way, in the catacombs of the first Christians! [7] There were tombs with the relics of martyrs killed in the Coliseum, a multitude of buried women and children – and then, suddenly, on the pier of one of the caves, on the wall, was a painting: heavenly, festal peacocks drawn in fine, elegant lines. The symbol of incorruption in early Christianity, in amazingly bright red, turquoise, and purple paint. The eternal Pascha! Yes, Butovo is our “Appian Way,” our “Golgotha.” It was December, and on the burial ditches, as if painted there by an artist, were crimson roses, carnations, and alstroemerias scattered everywhere. The caps of light from the burning candles here warmed the air above the grass, covered with a thick layer of frost.

Greater than death

And there they are, the Paschal symbols of this great and holy place: the tall, light, roofed memorial-cross (the work of the architect D. M. Shakhovskoy, son of the murdered Priest Michael Shika), [8] one for all those united by suffering and hope in the Resurrection; the wonderfully vivid icon of the Hieromartyr Seraphim (Chichagov); and the icon of the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia. The church itself is a symbol, small and wooden, erected right here on the shooting range, on the site of the forge where it is believed the first executions took place. It is remarkably light and warm inside. It is prayed in, especially on the day commemorating the saints of Butovo. It feels as though they are all here, next to us, with the small church holding everyone.

On the iconostas is a row of icons depicting the martyrs of Butovo. Among them are Archbishop Dmitri (Dobroserdov) of Mozhaisk, Archbishop Nicholas (Dobronravov) of Vladimir and Suzdal, Bishop Arkady (Ostalsky) of Bezhetsky, Bishop Jonah (Lazarev) of Velizh, and Bishop Nikita (Delektorsky) of Nizhniy Tagil. Here they all are: archimandrites, abbots, archpriests, priests, and parishioners.

Later, when I came alone, I asked Fr. Kirill’s blessing to photograph my beloved icon of the Hieromartyr Seraphim (Chichagov). I wanted to show it to my relatives and acquaintances, talking about Butovo to people who did not yet know anything about it or who were unable to come here. A woman working in the church lights the oil lamp. Lowering the lens, I see tiny droplets on the image. The icon is streaming myrrh. This happens before feast days and on the day of Vladyka Seraphim’s commemoration. With God there is no death for the saints; with Him they are all alive!

The Church traditionally celebrates the memory of the entire Synaxis of New Martyrs of Butovo on the fourth Saturday after Pascha. To those who have not yet been there, I can wish only one thing: that you hurry there to pray, to venerate the holy things, and to ask for forgiveness. After all, the majority of us grew up during a time when nothing was known about all this. And now, before rushing off to holy places in distant lands, it might be better and more useful to begin with that which is right next to us, but which, due to our own inattentiveness, has thus far been closed to our eyes. Today there is a newly constructed white church on the memorial complex in Butovo. It’s big. There is room enough for everyone.

Translated from the Russian.

Translator’s notes:

[1] “Black car” here translates voronok (literally, raven), the popular name given to the car used for the transportation of prisoners; this name was used because of car’s color (black) and because the raven was perceived as a bird of evil omen.

[2] Varvara Vasilevna Chichagova-Chernaya (1914-1999). Following a brilliant career in chemistry, during which she was highly decorated by the state while never belonging to the Communist Party, she was tonsured a nun in 1997 with the name Seraphima at the Novodevichy Convent in Moscow; shortly thereafter she was installed as abbess of the same convent, which had just been returned to the Church. She was the granddaughter of Metropolitan Seraphim (Chichagov) of Leningrad and Gdov, who was executed at Butovo on December 11, 1937, and subsequently glorified as a saint in 1997.

[3] The OGPU (Joint State Political Directorate under the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR) was a secret police body formed from the Cheka and at various times incorporated into the NKVD, which was later transformed into the KGB. It was responsible for the creation of the Gulag system and became the government’s main arm for the persecution of religious bodies.

[4] St. Catherine’s Monastery is located just outside the city of Vidnoye (formerly Rastorguyevo), a few miles south of Moscow city limits. Founded in 1660, it was closed in 1931. From 1938 to 1953 it housed the Sukhanovo Prison (a political prison of the NKVD notorious for its harsh conditions); later it was used as a police school. It reopened as a monastery in 1991.

[5] Nikolai Ivanovich Yezhov (1895-1940) was head of the NKVD under Stalin during the Great Purge (1937-1938). During the period of de-Stalinization the term “Yezhov era” was used to describe his reign.

[6] Fr. Vladimir Ambartsumovich Ambartsumov (1892-1937), born to an Armenian father and a German mother, converted to Orthodoxy in 1926 after many years of activity as a Protestant missionary and preacher; he was ordained to the priesthood the following year. Shot in Butovo on November 5, 1937, he was glorified as a saint in 2000. A great number of his descendents have gone on to the priesthood or to other active roles within the Church (including Archpriest Alexander Iliashenko, founder and chairman of the editorial board of Pravmir.ru, who is his grandson).

[7] Appian Way (Via Appia) was the principal road south from Rome in classical times. It contains several Christian catacombs, most notably those of Callixtus and Sebastian.

[8] Fr. Michael Shik (1887-1937) converted from Judaism to Orthodox Christianity in 1918 and was later ordained to the priesthood. He was shot in Butovo on the same day as Fr. Vladimir Ambartsumov, with whom he had served in Moscow, along with dozens of other clergy.