Source: Myriobiblos

From his book: “The Inner Kingdom“, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2001.

Heaven and earth are united today.

Hymn from the Vigil on Christmas Eve

O strange Orthodox Church!

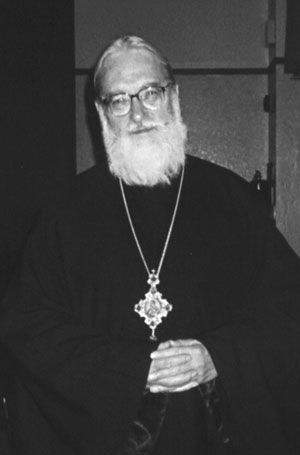

Father Lev Gillet

Third Part

Look not at the things that are seen…

There remained, however, one powerful dissuasive. If Orthodoxy is really the one true Church of Christ on earth, how could it be (I asked myself) that the Orthodox Church in the West is so ethnic and nationalist in its outlook, so little interested in any form of missionary witness, so fragmented into parallel and often conflicting “jurisdictions”?

There remained, however, one powerful dissuasive. If Orthodoxy is really the one true Church of Christ on earth, how could it be (I asked myself) that the Orthodox Church in the West is so ethnic and nationalist in its outlook, so little interested in any form of missionary witness, so fragmented into parallel and often conflicting “jurisdictions”?

In principle, of course, Orthodoxy is indeed altogether clear about its claim to be the true Church. As I read in the message of the Orthodox delegates at the Assembly of the World Council of Churches in Evanston (1954):

In conclusion we are bound to declare our profound conviction that the Holy Orthodox Church alone has preserved full and intact “the Faith once delivered to the saints.” It is not because of our human merit, but because it pleases God to preserve “His treasure in earthen vessels, that the excellency of the power may be of God” (2 Cor 4:7).In Constantin G. Patelos, The Orthodox Church in the Ecumenical Movement. Documents and Statements 1902-1975 (Geneva: World Council of Churches, 1978), 96. I imagine that Father Georges Florovsky was closely involved in drafting this fine statement. What a pity that Orthodox delegates at recent meetings of the WCC have not spoken with so clear a voice!

Yet there seemed to be a yawning gap between Orthodox principles and Orthodox practice. If the Orthodox really believed themselves to be the one true Church, why did they place such obstacles in the path of prospective converts? In what sense was Orthodoxy truly “one,” when, for example, in North America there were at least nineteen different Orthodox “jurisdictions,” with no less than thirteen bishops in the single city of New York? I give the figures for the year 1960, as found in the brochure Parishes and Clergy of the Orthodox, and Other Eastern Churches in North and South America together with the Parishes and Clergy of the Polish National Catholic Church, 1960-61, edited by Bishop Lauriston L. Scaife and issued by the Joint Commission on Cooperation with the Eastern Churches of the General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church. I have not included the non-Chalcedonians in my calculations. There are some splendid photographs in this publication. Some of my Anglican friends argued that the Orthodox Church was no more unified than the Anglican communion, and in some respects less so; if I moved, it would be out of the frying pan into the fire!

At this point I was helped by some words of Vladimir Lossky:

How many recognized in “the man of sorrows” the eternal Son of God? One must recognize the fullness there where the outward sense perceives only limitations and want… We must, in the words of St Paul, receive “not the spirit of the world, but the Spirit which is of God, that we may know the things that are freely given to us of God” (1 Cor 2:12), that we may be enabled to recognize victory beneath the outward appearance of failure, to discern the power of God fulfilling itself in weakness, the true Church within the historic reality. The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church, 245-46.

Looking at the empirical situation of twentieth-century Orthodoxy in the Western world, I was indeed confronted by apparent “failure” and “weakness;” and the Orthodox themselves did not deny this. But, looking more profoundly, I could also see “the true Church within the historical reality.” The ethnic narrowness and intolerance of Orthodoxy, however deep-rooted, are not part of the essence of the Church, but they are a distortion and betrayal of its true nature (of course there are also positive aspects to Orthodox Christian nationalism). As for the jurisdictional pluralism of the Orthodox Church in the West, this has specific historical causes; and the more visionary among Orthodox leaders have always seen it as at best a provisional arrangement that is no more than temporary and transitional. Moreover, there is an evident difference between the divisions prevailing within Anglicanism and those found within Orthodoxy. The Anglicans are united (for the most part) in outward organization, but deeply divided in their beliefs and in their forms of public worship. The Orthodox, on the other hand, are divided only in outward organization, but firmly united in beliefs and worship.

At this juncture I received a powerfully-worded letter from an English Orthodox priest with whom I was in correspondence, Archimandrite Lazarus (Moore), at that time resident in India. With reference to the Orthodox Church, he wrote:

Here I must warn you that the outward form of the Church [i.e., the Orthodox Church] is desperately wretched, in a word crucified, with little cooperation or coordination between the various national bodies, little deep use and appreciation of our spiritual riches, little missionary and apostolic spirit, little grasp of the situation or of the needs of our times, little generosity or heroism or real sanctity. My advice is: Look not at the things that are seen… Letter of April 11, 1957

I tried to follow Father Lazarus’s guidance. Looking beyond the outward and visible failings of Orthodoxy, I made an act of faith in “the things that are not seen” (2 Cor 4:18) — in its fundamental oneness, and in the underlying wholeness of its doctrinal, liturgical and spiritual Tradition.

In order to enter the Orthodox house, I had to knock upon a particular door. Which “jurisdiction” should I choose? I felt strongly drawn to the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile — the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR), as it is today commonly styled. What I admired in particular was its fidelity to the liturgical, ascetic and monastic heritage of Orthodoxy. While still sixteen I had come across Helen Waddell’s book The Desert Fathers, and from that moment I was fascinated by the monastic history of the Christian East. I found that most of the monasteries in the Orthodox emigration belonged to the Russian Church in Exile. In Western Europe I visited two women’s monasteries under its care, the Convent of the Annunciation in London, and the Convent of the Mother of God of Lesna outside Paris, and in both I was given a warm welcome. I also admired the way in which the Russian Church in Exile held in honor the New Martyrs and Confessors who had suffered for the faith under the Soviet yoke. On the other hand, I was disturbed by the canonical isolation of the Exile Synod. In the 1950s this was not so great as it has since become, for at that time there was still regular concelebration between Russian Exile clergy and the bishops and priests of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. But I saw that the Russian Church in Exile was becoming increasingly cut off from worldwide Orthodoxy, and that troubled me.

Had there existed in Britain a Russian diocese under the Ecumenical Patriarchate, as there was in France, then I would probably have joined it. As matters stood, the only Russian alternative to the Church in Exile was the Moscow Patriarchate. This had some distinguished members in Western Europe, such as Vladimir Lossky in Paris, Father Basil Krivocheine in Oxford, and Father Anthony Bloom (now Metropolitan of Sourozh) in London. But I felt it impossible to belong to an Orthodox Church headed by bishops under Communist control who regularly praised Lenin and Stalin, and who were prevented from acknowledging the New Martyrs slain by the Bolsheviks. I did not wish in any way to pass judgment on the ordinary Russian faithful dwelling inside the Soviet Union; they were under bitter persecution and I was not, and I do not suppose that in their situation I would have shown anything of the heroic endurance which they displayed. But, living as I did outside the Communist world, I could not make my own the statements issued by leading hierarchs of the Moscow Patriarchate in the name of the Church. As one of the Russian Exile priests in London, Archpriest George Cheremeteff, said to me: “In a free country we must be free.”

Despite my love of Russian spirituality, it became evident to me that my best course was to join the Greek diocese in Britain under the Patriarchate of Constantinople. As a Classicist, I had a good working knowledge of New Testament and Byzantine Greek, whereas at that time I had not studied Church Slavonic. If I became a member of the Ecumenical Patriarchate I would not have to take sides between the rival Russian groups, and I could maintain my personal friendships with members of both the Moscow Patriarchate and the Church in Exile. More importantly, Constantinople was the Mother Church from which Russia had received the Christian faith, and I felt it right in my quest for Orthodoxy to return to the source. Also I began to appreciate that, when eventually the Orthodox in Western Europe achieved organizational unity, this could only happen under the pastoral protection of the Ecumenical Throne.

So back I went to Bishop James of Apamaea, and much to my surprise I found him on this occasion willing to receive me almost at once. It is true that he warned me, “Please understand that we would never, under any circumstances, ordain you to the priesthood; we need only Greeks.” In fact I was ordained priest in 1966, eight years after my reception, by Metropolitan (later Archbishop) Athenagoras II of Thyateira, who had arrived in Britain in 1963/64. That did not worry me, for I was content to leave my future in the hands of God. I was only too delighted that the door had at last opened, and I entered without wishing to lay down any conditions. I saw my reception into Orthodoxy not as a “right,” not as something that I was entitled to “demand,” but simply as a free and unmerited gift of God’s grace. It gave me quiet happiness when Bishop James appointed Father George Cheremeteff as my spiritual father, and so I was able to remain close to the Russian Church in Exile.

Thus I came to the end of my journey; or, more exactly, to a new and decisive stage on a journey which had begun in my earliest infancy and which, by the divine mercy, will continue into all eternity. Shortly after Pascha in 1958, on Friday in Bright Week — the Feast of the Life-Giving Source — I was chrismated by Bishop James at the Greek Cathedral of St Sophia in Bayswater, London. At last I had come home.

Father Lazarus had warned me that I would find in the Orthodox Church “little generosity or heroism or real sanctity.” In retrospect, after more than four decades as an Orthodox, I can say that he was much too pessimistic. Doubtless I have been more fortunate than I deserve, but within Orthodoxy I have in fact found warm friendship and compassionate love almost everywhere that I have gone, and I have certainly enjoyed the privilege of meeting living saints. Those who predicted that, in becoming Orthodox, I would be cutting myself off from my own people and my national culture have been proved wrong. In embracing Orthodoxy, so I am convinced, I have become not less English but more genuinely so; I have rediscovered the ancient roots of my Englishness, for the Christian history of my nation extends back to a period long before the schism between East and West. I remember a conversation that I had with two Greeks soon after my reception. “How hard you must find it,” remarked the first, “to have left the Church of your fathers.” But the second said to me, “You did not leave the Church of your fathers: you returned to it.” He spoke rightly.

Needless to say, my life as an Orthodox has not always been “heaven on earth.” Repeatedly I have suffered deep discouragement; but did not Jesus Christ Himself foretell that discipleship means cross-bearing? Yet, forty-eight years later, I can affirm with all my heart that the vision of Orthodoxy which I saw at my first Vigil Service in 1952 was sure and true. I have not been disappointed.

I would make only one qualification: what I could not have appreciated back in 1952, but what today I see much more clearly, is the deeply enigmatic character of Orthodoxy, its many antitheses and polarities. The paradox of Orthodox life in the twentieth century is summed up by Father Lev Gillet, himself a Westerner who made the journey to Orthodoxy, in words which come closer to the heart of the matter than any others that I can recall:

O strange Orthodox Church, so poor and so weak… maintained as if by a miracle through so many vicissitudes and struggles; Church of contrasts, so traditional and yet at the same time so free, so archaic and yet so alive, so ritualistic and yet so personally mystical; Church where the Evangelical pearl of great price is preciously safeguarded — yet often beneath a layer of dust… Church which has so frequently proved incapable of action — yet which knows, as does no other, how to sing the joy of Pascha [Father Lev Gillet, in Vincent Bourne, La Quкte de Vйritй d’Irйnйe Winnaert (Geneva: Labor et Fides, 1966), 335]!