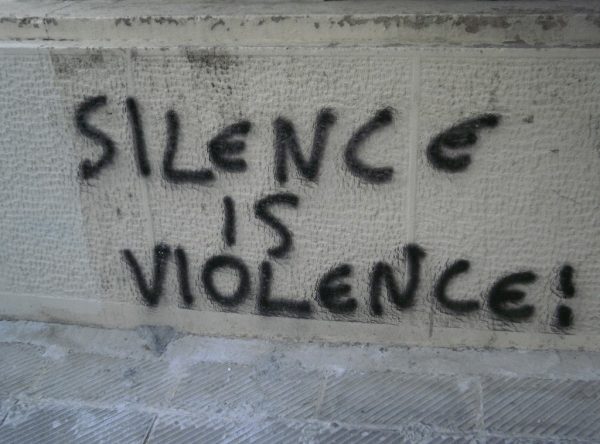

The phrase has been quoted frequently: “silence is violence.” It is the demand that some form of political speech or action, expression of opinion, meme-sharing, and the like, is required of every person or they are guilty (or at least complicit) in violence against a racial minority. There are any number of careful analyses of the depths intended by this phrase, examinations of the nature of violence, the nature of systemic prejudice, as well as the creation of justice. As much as I loathe political discourse, the present case serves as an excellent example of the nature of modernity and its subtle demands in our lives. No doubt, many have been persuaded to take up the chants that have become familiar of late. Others have probably been provoked to anger by such demands, even when they personally oppose racial injustice. What is going on?

First and foremost, the statement, “silence is violence,” is an attempt to shame those who do not join in the public outrage. There is the clear implication that anyone who remains silent is complicit in a crime. They are less than good people. That is the nature of shame: it tells us that we are bad. Anytime we are shamed, we are provoked to anger or to some form of inner misery. We want to either placate the accuser or to crush them. We’re wired that way. It is, and always has been, a powerful means for controlling human behavior.

Throughout much of Western history (both Medieval and the early modern period) public shaming was perhaps the most common form of punishment. The two most frequent forms were the stocks (where a person was simply locked in a wooden platform and put on public display for a time) and the pillory (where the head was held in place by an iron contraption so that a person could not move, nor turn the face away in shame). There were other cruelties added, including nailing the ears, or cutting them off, or whipping the individual as well. The point of these punishments was not so much the suffering involved – it was the public display of the suffering. It was common for the public to ridicule an individual in the stocks or pillory, throwing rotten food, spitting, and the like. The crucifixion of Christ was simply an early, more cruel form of this very thing.

The death penalty has been in place through most of history, and only ceased to be a public form of punishment in relatively recent times. Crowds gathered to watch and jeer as a criminal was hung. The hangman’s noose, the pillory, and the stocks, were a form of social media in their time – the Facebook of a village.

There is a long history of public demonstrations and riots. Crowds have sought to overthrow emperors, change policies, single-out and execute individuals, etc. Indeed, the sorry history of racial lynching in America belongs in the darkest corner of such actions. The passions of crowds often seem to empower a group to do something that a single individual would never dare or even wish. There is an anonymity that comes about in which personhood begins to be obscured and lost. It is a dangerous episode in the life of any nation, regardless of the cause.

Sadly, it also seems to hold great promise to many. In terms of the passions, it feels like something is being done (when “something must be done!”). Of course, in America, as a news-cycle fades, so the crowds thin, and whatever “must be done” likely languishes or morphs into something else entirely.

I have voiced my skepticism about the “modern project” time and again, with the argument that it represents a distortion of classical Christianity, while, at the same time, being a disingenuous collection of slogans that provide cover for the true work that goes by its name. It is not building a better world. It is more accurate to say that modernity is always building a bigger profit.

There is some level on which democracy “works.” It is, however, not nearly as transparent nor obvious as it would seem. The history of nations demonstrates time and again that the “powers that be” are, primarily, “powers.” They are not philosophical or theoretical entities. Unmasking the powers is always difficult, and sometimes quite frightening. On some level, there is always something “demonic” at work. In the Scriptures, the distinction between the government of the empire and the “principalities and powers” of the demonic anti-hierarchy frequently seems blurred. Though Christ was “officially” put to death by the Roman state, St. Paul also describes the crucifixion as an action of the “rulers of this age” (1 Cor. 2:8), a clear reference to demonic powers. By the same token, Christ’s death and resurrection are a defeat of these same powers.

Democracy does not represent a new age in which these powers are no longer at work. That which was at work in Rome, in the Middle Ages, in the Soviet Union, in the European Union, is that which is at work in all of the states of the present time. There is no such thing as a “secular” state.

The real question for Christians is not “how should I vote,” but “how should I live?” There is nothing wrong in voting one’s conscience. But there is much wrong in imagining ourselves to have power in the manner in which it is often told to us. This is the simple truth: steadfast, sacrificial prayer is of far greater worth than every so-called political action. God sustains the world through the prayers of the saints. Not even a modicum of justice is sustained by the votes of a majority.

We cannot, through voting, make the world to be a place any better than our own hearts. If we cannot rightly govern even so little, how do we imagine ourselves to be governing so much? If God could turn the wicked heart of Pharaoh towards mercy, can He not do the same in our own day? St. James wrote: “…for the anger of man does not produce the righteousness of God.” (James 1:20)

Many people would agree that they have rarely seen as much anger and hatred in our public lives as we are seeing at the moment. Righteousness, the true godly relationship between people, is a profound work of peace-making. We cannot make peace with anger. “Acquire the Spirit of peace and a thousand souls around you will be saved.” That is simply the truth regarding any righteousness in this world. Such peace flows easily from silence, if the silence is wrapped in prayer.