Hark when the night is falling, hear, hear the pipes are calling,

Loudly and proudly calling, down through the glen.

There where the hills are sleeping, now feel the blood a-leaping,

High as the spirits of the old Highland men.

Towering in gallant fame, Scotland my mountain hame,

High may your proud standards gloriously wave,

Land of my high endeavour, land of the shining river,

Land of my heart for ever, Scotland the brave!

– Traditional Folk Song

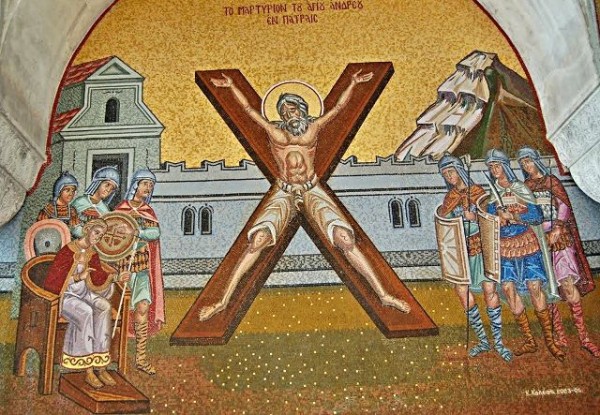

The Cross of Saint Andrew – the blue and white emblem of Scotland’s patron saint – is believed to be the oldest continuously used flag in the world. Simple in its design, it has withstood centuries of political and religious turmoil, and remained the standard for Christian Scots, as well as those who have forgotten the reason their banner bears the Cross. (For the record, Saint Andrew was martyred on an X-shaped cross). Like the people for whom it flies, Saint Andrew’s Cross has proven its resilience and strength.

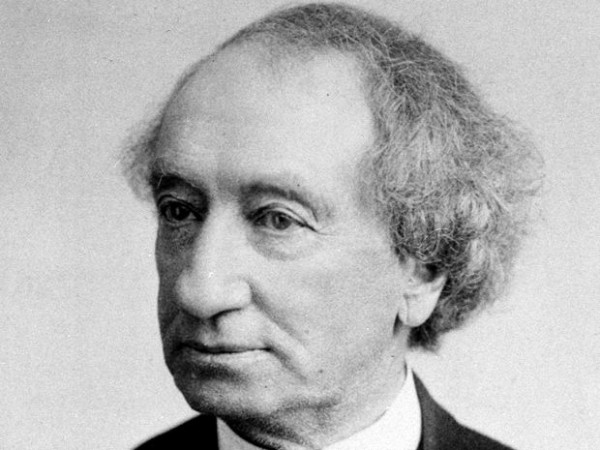

The endurance of Saint Andrew’s Cross is seen in the presence it still has in Scotland’s largest emigree nation – Canada. In a country whose first Prime Minister was a MacDonald, whose first woman Prime Minister was a Campbell, and which boasted no fewer than nine Prime Ministers of Scottish ancestry (only five Prime Ministers were French), it is not a stretch of the imagination to suggest that Scotland still has at least a pint or two of its own running through the bloodstream of Canadian culture. Official ceremonies, academic awards, university names and traditions, along with the pipers who lead their processions – all these have been inherited from the practices of the Celts of Scotland, through their Canadian children.

The Cross of Saint Andrew can be found on five Canadian provincial flags, either within the Union Jack, or in the mirrored image of the flag of Canada’s New Scotland, Nova Scotia. Yet those who trace their roots from that chilly isle to this great land do not often read back far enough to discover the essence of Scotland’s Celtic roots, roots that reflected the faith of Saint Andrew for nearly one thousand years in a Celtic Church that was vibrant, independent, and fully Orthodox.

For those who entertain new-agey illusions about the Celtic Church, there is bad news: Celtic Christian worship was in most ways very similar to the life of Orthodox parishes today. What is very clear, Celtic Christians had far less in common with the free-wheeling nature worship one might find in certain Protestant or Roman Catholic circles than it did with the spiritual life of Greek monasteries in Byzantium. This shouldn’t surprise us: the Greeks and the Celts had the same faith and liturgical life, while the Christian Celts and the modern western confessions, distorted by the Great Schism and the Protestant Reformation, do not.

In his classic book, Liturgy and Ritual of the Celtic Church, F.E. Warren thoroughly outlines this common spiritual inheritance. Concrete examples are numerous. Celtic Christians fasted on Wednesdays and Fridays, the universal observance of the Church in the first millennium. They rejected the claims to universal authority that Popes of Rome often claimed over Church decisions in custom, belief, and practice, and resisted innovative changes to early Church practices, including the Church calendar. The Celts observed a highly ascetical life, strongly shaped by the widespread presence of monasteries, where monks and non-monastics alike would say the services of the Hours on a daily basis.

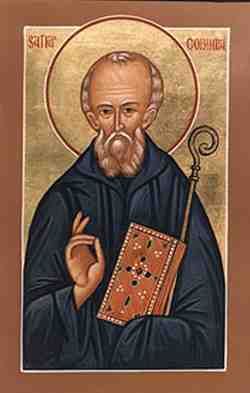

The presence of married priests among the Celts did not arise out of a special dispensation from Rome, but rather, from the Celtic Church’s . Around 400 A.D., the Celtic Church was large enough to attract the attention of Saint Jerome, who noted that the Celts were in communion with Rome, Gaul, and Africa – part of the universal witness to the One Faith. At the Sixth Ecumenical Council, Saint Wilfred affirmed the Orthodoxy of the Celts, despite the concerns of their critics that some local Celtic customs were at variance with Rome. Saint Columbanus, the great champion of the independence of the Celtic Church, repeatedly upbraids the Roman Church for its claims to universal authority – the timeless Orthodox defense against the extension of papal powers. “Let no bishop leave their diocese,” he thunders, “lest he interfere with the affairs of the Church.”

The artistic life of the Celtic Church shows a warm interplay between the images of the universal Orthodox witness, and local Celtic traditions. Architectural decoration, ribbons in stone carvings, and giant initial letters in manuscripts reflect a North African influence, a fact not lost on most modern authorities on the Celts. The use of icons, and iconostases, were seen in various Celtic churches, including the burial place of Saint Brigid, the great Celtic saint. Celtic depictions of Christ as a child, wrapped in mummy-like swaddling bands, reflect Egyptian and Byzantine iconography. Like Orthodox bishops today, Celtic bishops used staves bearing the heads of snakes, like Moses in the desert. We can only imagine how much more we would know if the persecutions of Diocletian (305-313AD) had not destroyed many churches in the Celtic diaspora on the European continent (the earliest Celtic Church dated from around 200 A.D).

Liturgically, the Celtic Liturgy will seem familiar to Orthodox Christians, which is not a surprise in light of the fact that it represents one of the oldest Orthodox liturgies. The celebrant faced the altar, behind an icon screen, offering up the sacrifice of the Holy Mysteries of Communion with both elements together in the chalice. Communion was almost certainly delivered on a spoon; many such spoons have been found. A little water was added to the chalice before Communion, just as it is in the Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom. There was even use of a small Eucharistic knife or spear, used for dividing Communion before it was placed in the chalice.

The souls of the departed were uniformly commemorated at the Liturgy, with long lists of saints, both local and universal, named at the services (there is some suggestion that the Celts did not ask for specific prayers from the saints; their general intercessions were assumed). The episcopal blessing, at Liturgy and perhaps other times, was bestowed in the manner of the Greek Church, with the fingers of the celebrant in the form of the Christogram (IC XC).

A variety of other liturgical parallels exist. Women were always veiled in the Celtic Church for the reception of Holy Communion. It is known that the Celts served an unction with blessed oil (as well as chrismation), and performed a ritual washing afterwards, much like the Slavic churches do to this day (the Greek custom of covering a newly baptized child with olive oil is an expansion on this practice, which works very well in Mediterranean climates, but which finds its limits in chilly northern climes). There is some suggestion that the Celts celebrated the Liturgy without wearing shoes, in the manner of the Copts of Egypt (just like the North American saint of our time, Saint John Maximovich). Noting the Celtic monastic connection with the Copts, this would come as no surprise.

It should not surprise us to find these similarities, since in comparing the Celtic Church to the Church in Byzantium, or to Orthodox Christianity today, we are in fact comparing the Church to itself. The Orthodox Christianity of the Apostles, of the Ecumenical Councils, of the Byzantines, the Slavs, the Arabs, and the Celts – it is one faith, not many. The Celtic Church was astonishingly similar to Orthodox life today – because it was Orthodox.

The inheritance of Saint Andrew, whose proud banner waves in front of many a Presbyterian church in Canada, is not to be found inside these churches. Nor is the bold heart of the Celtic Christians of Scotland to be found at Burns dinners or chip shops or the Lodge of the Scottish Rite. The banner of the Celts is an Orthodox Christian one; it always has been. And it is a banner that flies proudly in the hearts of hundreds of thousands of Canadians, who still await the rediscovery of their own Orthodox Celtic roots, which cannot be found in the western confessions. These confessions of the last thousand years would have been virtually unrecognizable to the Celts of a millennium ago – the same Celtic Christians who would feel right at home in any Orthodox church in North America today.

Sir John Alexander Macdonald (Liberal-Conservative Party of Canada) was Canada’s first Prime Minister

Canada’s first Scottish leader, Prime Minister John A. MacDonald, lies buried in the cemetery of a parish church in Kingston, Ontario, the same building that is home to the Orthodox Community of Saint Gregory of Nyssa. Perhaps it is in such a representation that we can rediscover the heritage of the founders of our own nation, its own enduring and brave Orthodox roots, put down in Celtic lands by the same Orthodox monastic saints who once made pilgrimage across the ocean to our own land. For it is only these roots that will keep Saint Andrew’s banner long and gloriously waving – not just in our hearts, but in our lives.

Background note: The St. Andrew’s cross is a distinctive shape because the Apostle Andrew, who would later become the patron saint of Scotland, asked that he not be crucified on a cross of the same shape as that on which Jesus Christ was executed. (See the Great Synaxarion of the Orthodox Church, November 30th) The legend of the birth of the Scottish flag takes place circa AD 832 near Athelstaneford in East Lothian. Angus mac Fergus, King of the Picts, and Eochaidh of Dalriada faced off against the army of Athelstane, King of Northumbria, comprising Angles and Saxons. On the eve of the battle, it is said that the Scots saw the clouds in the evening sky arranged in a formation exactly like that of St. Andrew’s cross. The Scots saw this as a harbinger of their victory. When they were victorious the following day, they adopted a white St. Andrew’s cross on a field of azure blue as their national standard.