Source: Orthodox America

For my first, and best, teachers of Greek — Dr. Melvin Mansur and Fr. Ioannikios (Abernathy)

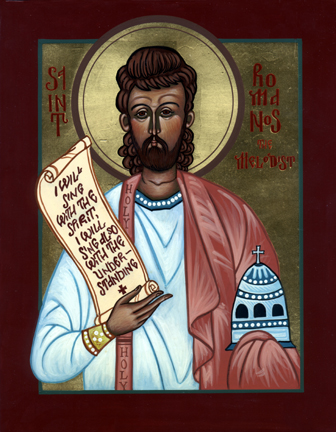

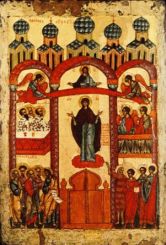

The Orthodox Church exhorts us “to sing with understanding” (Ps. 46:8, I Cor. 14:15), that is, to be more than passive spectators or consumers of “sacred culture.” A wonderful education awaits us if we actively seek out and study its resources for the spiritual life – patristic writings, lives of saints, church history, iconography, and Divine services. The faithful are invited to own these treasures, including church music and hymnography, which are often wrongly regarded as belonging only to certain “experts.” In the attentive participant, the wealth of liturgical verse inspires many questions: When and by whom were the texts of the various service books composed? What are the genres of verse (troparion, irmos etc.) and how are they distributed in services of different types? How did the poetry and music of the Church develop and how do they differ from secular arts? No account of this subject would be complete without mention of Saint Romanos Melodos, whom many scholars consider to be not only the preeminent poet of the Byzantine period but the greatest poet of the early Middle Ages in any language. He was the recipient of a poetic tradition that looked back to Saints Ephraim of Syria, Proclus, and Melito of Sardis. His heirs, in turn, were the great hymnographers of the following centuries: Saints Andrew of Crete, John Damascene, Germanos and Cosmas among them. His prominence in this choir of Orthodox hymnographers is emphasized in many icons of the Protection of the Theotokos, such as the Novgorod example printed here. In what follows, I introduce Saint Romanos’ art as a Christian appropriation of ancient “lyric” and “dramatic” concepts for which his Lament of the Theotokos supplies a vivid illustration.

The Orthodox Church exhorts us “to sing with understanding” (Ps. 46:8, I Cor. 14:15), that is, to be more than passive spectators or consumers of “sacred culture.” A wonderful education awaits us if we actively seek out and study its resources for the spiritual life – patristic writings, lives of saints, church history, iconography, and Divine services. The faithful are invited to own these treasures, including church music and hymnography, which are often wrongly regarded as belonging only to certain “experts.” In the attentive participant, the wealth of liturgical verse inspires many questions: When and by whom were the texts of the various service books composed? What are the genres of verse (troparion, irmos etc.) and how are they distributed in services of different types? How did the poetry and music of the Church develop and how do they differ from secular arts? No account of this subject would be complete without mention of Saint Romanos Melodos, whom many scholars consider to be not only the preeminent poet of the Byzantine period but the greatest poet of the early Middle Ages in any language. He was the recipient of a poetic tradition that looked back to Saints Ephraim of Syria, Proclus, and Melito of Sardis. His heirs, in turn, were the great hymnographers of the following centuries: Saints Andrew of Crete, John Damascene, Germanos and Cosmas among them. His prominence in this choir of Orthodox hymnographers is emphasized in many icons of the Protection of the Theotokos, such as the Novgorod example printed here. In what follows, I introduce Saint Romanos’ art as a Christian appropriation of ancient “lyric” and “dramatic” concepts for which his Lament of the Theotokos supplies a vivid illustration.

I

At many points throughout the various cycles of services, the Church looks back to sixth-century Byzantium for a fragment of the extensive oeuvre of Saint Romanos. When we sing his kontakia of the Nativity, “Today the Virgin Gives Birth,” or of Pascha, “Though Thou Didst Descend into the Tomb,” we but graze the surface of a rich legacy that is today little known and appreciated. It would be hard to overestimate the importance of Saint Romanos as a cantor, composer, and interpreter of the Orthodox world-view. His beautifully crafted poems set a standard for all time as art that clearly and accurately communicates the teaching and spirit of the ‘cumenical Councils and ascetic instructors. (Later termed “kontakia,” these cantica are not to be confused with the designation, “kontakion,” for short verses in current usage.)

Even from the modest number of surviving kontakia (about sixty out of over a thousand), one marvels at the wide range of dramatic representations devoted to prayerful remembrance, instruction, and edification. Biblical events, lives of saints, and the spiritual life are illustrated in lively narratives distinguished by remarkable poetic technique. The Oxford text of P. Maas and C. Trypanis, for example, presents thirty-four kontakia on feasts of the Lord, five on major feasts such as the Annunciation and Nativity of the Theotokos, seven on Old Testament subjects, three devoted to martyrs, and ten on other topics such as fasting, repentance, and the monastic life. One of the most influential hymnographers of the Church, Saint Romanos was celebrated above all for his glorious music (which has not survived). He is Melodos, “the Melodist,” to the Greeks and Sladkopevets, “Sweet-singer,” in the Slavic tradition.

Saint Romanos was born in Syrian Emesa some twenty-five or thirty years after the Council of Chalcedon (451) and came to Constantinople around the turn of the century. From references in his compositions On the Ten Virgins (II) and On Earthquakes and Fires, we know that he was – perhaps as a “court” deacon and cantor — in Constantinople to witness the Nika riots of January 532. There is also mention in the kontakia of the earthquakes of the mid ‘fifties (July 552, August 555), and apparently even the collapse and rebuilding of Hagia Sophia (May 558 – December 562). His life offers an inspiring example of a man who, despite humble beginnings and natural limitations, brought forth great fruit through piety and perseverance (For details see Orthodox America Vol. XV, No. 3 [135], September-October 1995, p. 5).

The Greek language had undergone fundamental changes since the Classical period and, by the sixth century A.D., had long been the vehicle of Christian theology and prayer. The departure from Latinity accompanied an aggressive suppression of pagan traditions. Still, the classical legacy in literature, science, philosophy and art haunted “contemporary” Greeks then, as it does now, by being both spiritually alien and, yet, seemingly unsurpassable. The lyric poetry of Alcaeus, Pindar and other “stars” of the genre had enjoyed a special prestige as did the dramatic classics of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. Ancient inventions of particular beauty and sophistication, the lyric marriage of music and words and the theatrical fusion of poetry, song and dance were competitive arts requiring considerable learning and skill.

Significantly, Saint Romanos has been hailed the “Byzantine Pindar” and a “spiritual dramatist,” that is, a Christian composer whose poetry was in the same league as that of the ancients, technically and aesthetically. It is important to note, however, that he helped forge a new and authentic Christian idiom that was not tied directly to the language and forms of the pagan past. Indeed, unlike classicizing authors such Saints Clement of Alexandria and Gregory of Nazianzus, Saint Romanos was not bound by the strait-jacket of ancient expression and versification. His Greek is a rich blend of scriptural phraseology, traditional hymnographic patterns, and even contemporary speech.

The ancient concepts of “lyric” and “drama” are fundamental to Saint Romanos’ kontakia, to be sure, but in a new transformation, that is, elevated and sanctified in the context of Divine service. The mythology and socio-political competition of festivals such as the Pythian games and City Dionysia were replaced by Scripture, theology and prayer offered “with one mouth and one heart” by the Church. Thus Saint Romanos’ art reflects the cultural transformation of ekklкsia from “civic, legislative assembly” (in classical Athens, for example) to “assembly of the Christian faithful,” the Church. The kontakion, in its developed form, was a lyric homily in which instruction of the faithful was bound to a strong narrative (“story-line”) and realized as a play of sorts with characters and commentary. Towards the end of the seventh century, the kontakion was replaced by the familiar form of the kanon, a non-dramatic and non-narrative hymn of praise consisting of odes, each with many stanzas and each having a different rhythmic and melodic form. In the kanon, the lyric of praise prevailed over the kontakion’s dramatic and edifying mode of story-telling as practiced by Saint Romanos.

The performance of a kontakion in itself illustrates well the appropriation of ancient lyric and dramatic concepts. The lyre, flute, and play-acting of the ancient festivals gave way to stately interaction between a soloist and a choir in a temple of God. The kontakion would be sung in place of a spoken homily after the reading of the Gospel at one of the services comprising the daily cycle, such as Vespers or Matins. While we cannot be certain of details, it is reasonable to assume that a cantor, occupying a central position in church, would alternate with antiphonal choirs in the delivery. Following a unique introductory verse (prooimion) each strophe of a kontakion was sung to the same elaborate melody and concluded with a refrain that remains constant throughout. As we shall see below, the dramatic symmetry of a kontakion is strictly articulated by the strophic unit – clearly the basic module of performance – which is, in turn, asserted throughout by means of a melodic and rhythmical identity similar to classical lyric in complexity and variety, and every bit as disciplined. In a likely distribution of roles, the main narrative portion of each strophe would be chanted by a virtuoso cantor, while the choirs sang the refrains. It was an annual tradition, for example, to perform the Nativity kontakion in the Emperor’s palace with two choirs (with, perhaps, less emphasis on the soloist). Consequently, a “dramatic” kontakion involving patterned dialogue could be divided between choirs with the cantor serving more in the capacity of moderator or director. From a glance at the metrical schemata in the Oxford or Budй editions, it is clear that the kontakia employed complex melody and rhythm. The performance dynamic outlined above suggests that Saint Romanos’ dramatic “vision” was directed at bringing divine events and personages to life in choral dialogue that was as delightful aesthetically as it was effective intellectually and spiritually. Let us consider this latter, “dramatic,” aspect in the example of a kontakion of Passion Week, Thrкnos tкs Theotokou (Lament of the Theotokos: quite clearly a major inspiration for the similarly titled but later composition still current in parish and monastic practice today.)

II

The kontakion of Great Friday, “Come let us sing praises of Him Who was crucified for us,” and its oikos are the tip of a poetic iceberg drawn from Saint Romanos’ full composition. In current editions (e.g., Maas-Trypanis 19) this composition consists of a four-line prooimion and seventeen ten-line strophes, making it roughly comparable in length to the well-known Akathistos Hymn. There can be little doubt that it was an important contribution on the part of Saint Romanos to depict the suffering of the Mother of God before the Crucifixion. Hers is the main voice amidst those of the women who “bewailed and lamented” Christ along the sorrowful way to Golgotha (Luke 23:27-31). The poet uses this context, which mirrors the language of lamentation, to depict Her natural humanity and motherhood: At these words, the All-Pure Mother, / still more afflicted in spirit, cried out thus / to the One Who was ineffably made flesh and born from her; / “Why dost Thou tell me, Child, that I be ‘not carried away with the other women?’ / Just as they [had children] in their bellies, I carried Thee, my Son, in my womb, and gave Thee milk from my breasts. / How then dost Thou wish for me now not to weep for Thee, Child, / as Thou hastenest to endure death unjustly? / Thou Who raised the dead, / my Son and my God” (Strophe 6b).

Inconsolable weeping emerges as the leading mood of the poem. The first strophe begins with the Theotokos “following wearily with the other women, crying ‘Where art Thou going, Child?'” Throughout, down to the final exchange, she continues to weep, overwhelmed by love and sorrow: “I am vanquished by loving grief, Child,” she cries in the fifteenth strophe, and repeats her very first request: “Truly I cannot endure to be in my chambers while Thou art on the Cross; I at home, while Thou art in the tomb.” An important, if overlooked, aspect of Saint Romanos’ teaching in this kontakion concerns proper mourning in a Christian context. Here, like many Church fathers before him, he connects a discourse on the Passion with a lesson on the Christian attitude towards death. In this connection, the poet represents the Saviour as instructing the Virgin not to be “carried away with the other women,” and to reject pagan traditions of lamentation. The faithful, in other words, now have the Resurrection, whereby Christ “trampled death by death,” once and for all invalidating desolate and hopeless displays of grief. Addressing a contemporary situation, Saint John Chrysostom had written: “What are you doing woman? …. [W]ould you tear your hair, rend your garments and wail loudly, dancing and preserving the image of Bacchic women, without regard to your offense to God?” (PG LIX 346; see also St. Basil the Great PG XXXI 229c). In a gentler, but similar tone, Saint Romanos has the Saviour say:

Lay aside thy grief, Mother, lay it aside. / Lamentation does not befit thee who hath been named ‘Blessed.’ / Do not obscure thy calling with weeping. / Do not liken thyself to those who lack understanding, All-Wise Maiden. / Thou art in the midst of My bridal chamber (Strophe 5). Saint Romanos’ Thrкnos tкs Theotokou is devoted to visualizing the via dolorosa through a dramatic dialogue rooted in the concept of Mary as Birth-Giver of God (Theotokos). Herein is another important theological point of the kontakion: to reinforce the formulation of the (Third) Ecumenical Council at Ephesus identifying the Virgin as the Birth-Giver of God (Theotokos). The refrain of the hymn, “My Son and My God,” as well as its structure are, accordingly, informed by the polarity of the human and divine aspects of Christ’s relation to His All-Pure Mother. As in all kontakia, the theological program here is framed by the prooimion and concluding strophe. In the former, the Mother of God simultaneously asserts her natural motherhood and acceptance of the Crucifixion as having transcendent significance. The clause concluding the proem emphasizes the paradox of the Passion: “Even though Thou dost endure the Cross, Thou art [remainest] my Son and my God” (God cannot be put to death; a mortal son would be taken from his mother by death).

In the final strophe, similarly, the Saviour is addressed as “Son of the Virgin, God of the Virgin,” both to summarize the doctrine of redemption and to underscore that, as a woman and mother, the Theotokos required divine support to find the courage (parrhкsia) to accept the harsh paradox of Golgotha. Between these two bookends is a series of direct exchanges of increasing frequency, organized by the pious narrator’s commentary into symmetrical groups of strophes. The Virgin holds forth for the first three strophes and is answered in as many. The Virgin speaks again for two strophes to which Christ responds in two. The Virgin then has a single strophe that inspires the poem’s climax: a theological speech in which the Saviour presents the redemption, the healing of our “ailing” forefathers, by means of a medical metaphor. The instruments of the Passion are transformed to be a healer’s tools: “Like a doctor, I will strip down and reach where [the ailing Adam and Eve] lie / and treat their wounds. / I will perform surgery on their sores and calluses with the spear. / I will also use vinegar to staunch their wound. / Having explored their ulcer with the surgical probe of the nails, I will apply My cloak as a dressing. / And then, carrying My Cross as a medicine chest / I will make (full) use of it that thou mightest sing with understanding, / ‘Through suffering, He destroyed suffering / my Son and my God’.” (Strophe 13)

Thus, through his song – an emotional drama set on Great Friday – Saint Romanos leads us to an understanding of three specific, interrelated points: 1) the reality and significance of regarding the Virgin as Birth-Giver of God; 2) the salvation wrought for all mankind as an act of healing by Christ in His Passion; and 3) the consequent need to adopt and practice a new, Christian, attitude towards death. The simple and deep images of the Thrкnos make a strong impression that is not easily forgotten. What better way to communicate the exalted theology of Passion Week to an urban flock, many of whom were illiterate and uneducated? As we come to appreciate the richness and wisdom of the texts handed down by the Church in its services, it is instructive to remember a teacher of recent times, Saint John Maximovitch: More than any modern theologian, he used the services of the Orthodox Church as an inexhaustible patristic resource for works such as Mary, the Birth-Giver of God. His profound and authoritative studies of tradition and theology are frequently supported by, and illustrated from, the Divine services. In this, Saint John, like Saint Romanos fourteen centuries before him, reveals the Church to be the most effective and direct education for those who wish to learn to “sing with understanding” to their God!