Today is the 9th anniversary of the repose of Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh. We offer you the following essay written in 2003 by Jim Forest, International Secretary of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship.

“We should try to live in such a way that if the Gospels were lost, they could be re-written by looking at us.”

– Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh

One of the significant events in the Orthodox Church this year was the death from cancer on August 4th of a remarkable, indeed saintly, bishop: Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh. He was 89. For many years he headed the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate in Great Britain.

Though he was not a member of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship’s advisory board, Metropolitan Anthony’s letters and conversations with those responsible for OPF played an important role in the path the Fellowship has followed. He passionately believed that peacemaking required active, warrior-like combat with evil. He had a strong aversion to the word “pacifist,” not only because it sounded with “passive-ist” but because of unpleasant encounters with self-righteous people quick to denounce those who failed to share their ideology. He preferred the phase “a man — or woman — of peace” which meant, he explained, a person “ready to work for the reconciliation of those who have grown apart or turned away from one another in enmity.” He was unhesitating in declaring that hatred is incompatible with Christianity, but saw the use of violence against Nazism in the Second World War as a lesser evil.

He sometimes told the story of an encounter he had during a retreat for university students. “After my first address one of them asked me for permission to leave it because I was not a pacifist.” “Are you one?” Metropolitan Anthony replied. “Yes.” “What would you do,” he asked, “if you came into this room and found a man about to rape your girl friend?” “I would try to get him to desist from his intention!” the man replied. “And if he proceeded, before your own eyes, to rape her?” “I would pray to God to prevent it.” “And if God did not intervene, and the man raped your girl friend and walked out contentedly, what would you do?” “I would ask God who has brought light out of darkness to bring good out of evil.” Metropolitan Anthony responded: “If I was your girl friend I would look for another boy friend.”

Yet, while hating passivity in the face of evil, his own commitment to reconciliation had deep roots in his life. During the years the German army occupied France when he was a physician active in the Maquis, a section of the French resistance, he had occasion to use his medical skills to save the life of a German soldier. Condemned for this act of Christian mercy by colleagues in the resistance, it was an action which almost cost him his own life. He was nearly executed. It was in that crucible of expected death that he decided, should he survive the war, that he would become a monk.

On another occasion, the roles were reversed: it was a German who saved his life. He had been arrested by the occupation forces. During a long interrogation, he was asked what he thought of National Socialism. “I assumed that I was going to be carted off to a camp anyway,” he recalled, “so I decided to tell the truth. I told them that I hated their system, and it would soon be overthrown by their enemies.” After a long pause his interrogator replied: “Quickly, out through that door. It isn’t guarded.” Thus he escaped.

He faced life-threatening situations many times. When the war ended, he found himself among Charles de Gaulle’s bodyguards during de Gaulle’s triumphal entry into Paris. He remembered taking cover from snipers while the General ignored the bullets.

Metropolitan Anthony stood ramrod straight. To the end of his life one could easily imagine him as an military officer if only he changed from his monastic robes into an army uniform. No one could have imagined, when he was a youth, that monastic vows, ordination as a priest and consecration as a bishop lay ahead or that he might become one of the great Christian missionaries of his era.

He was born Andrei Borisovich Bloom on the 19th of June 1914 in Switzerland, where his father was serving as a member of the Russian Imperial Diplomatic Corps. His mother was the sister of the Russian composer Alexander Scriabin. Molotov, Stalin’s comrade, was also a relative. Shortly before the First World War, the family returned to Russia, but soon left again for a diplomatic assignment in Persia. His vivid memories of Persian shepherds, “minute against the hostile backcloth of the vast Persian plain” while protecting their flocks, made him a convincing preacher on the parable of the Good Shepherd.

After the Russian Revolution, the family set out through Kurdistan and Iraq. When they sailed for Britain in a leaking ship, he hoped to be shipwrecked — he was reading Robinson Crusoe at the time. Instead, he was put ashore at Gibraltar where the family’s luggage was mislaid. Some fourteen years later it was returned with a bill for 1.

In 1923, the family at last settled in Paris, adopted home to thousands of impoverished Russian refugees. Here his father became a laborer while his son went to a rough school. Andrei evinced an early suspicion of Roman Catholicism, which prompted him to turn down a place at an excellent school when the priest in charge hinted that he ought to convert.

After reading classics, he went on to study physics, chemistry and biology at the Sorbonne School of Science. In 1939 he was qualified as a physician.

Like so many of his contemporaries, he grew up with no belief in God and at times voiced fierce hostility to the Church. But when he was eleven, he was sent to a boys’ summer camp where he met a young priest. Impressed by the man’s unconditional love, he reckoned this as his first deep spiritual experience, though at the time it did nothing to shake his atheist convictions.

His opinions were undermined, however, a few years later by an experience of perfect happiness. This came to him when, after years of hardship and struggle, his family was settled under one roof for the first time since the Revolution. But it was aimless happiness, and he found it unbearable. He found himself driven to search for a meaning to life and decided that if his search indicated there was no meaning, he would commit suicide.

After several barren months, he reluctantly agreed to participate in a meeting of a Russian youth organization at which a priest had been invited to speak. He intended to pay no attention, but instead found himself listening with furious indignation to the priest’s vision of Christ and Christianity.

Returning home in a rage, he borrowed a Bible in order to check what the speaker had said. Unwilling to waste too much time on such an exercise, he decided to read the shortest Gospel, St. Mark’s. Here is his account of what happened:

While I was reading the beginning of St. Mark’s Gospel, before I reached the third chapter, I suddenly became aware that on the other side of my desk there was a presence. And the certainty was so strong that it was Christ standing there that it has never left me. This was the real turning-point. Because Christ was alive and I had been in his presence I could say with certainty that what the Gospel said about the crucifixion of the prophet of Galilee was true, and the centurion was right when he said, “Truly he is the Son of God.” It was in the light of the resurrection that I could read with certainty the story of the Gospel, knowing that everything was true in it because the impossible event of the resurrection was to me more certain than any other event of history. History I had to believe, the resurrection I knew for a fact. I did not discover, as you see, the Gospel beginning with its first message of the annunciation, and it did not unfold for me as a story which one can believe or disbelieve. It began as an event that left all problems of disbelief behind because it was a direct and personal experience.

During the Second World War, Metropolitan Anthony worked for much of the time as a surgeon in the French Army, but also, during the middle of the war, was a volunteer with the French resistance. In 1943, he was secretly tonsured as a monk, receiving the name Anthony. Since it was impractical for him to enter a monastery, the monk who was his spiritual father told to spend eight hours a day in prayer while continuing his medical work. When he asked about obedience, he was told to obey his mother. He continued to live a hidden monastic life after the war, when he became a general practitioner.

In 1948, when he was ordained priest, revealing then that he had been a monk for the previous five years. The following year he was invited to become Orthodox chaplain to the Fellowship of St. Alban and St. Sergius in England. The Fellowship had been founded in 1928 by a group of Russian Orthodox and Anglican Christians to enable them to meet each other and to work together for Christian unity. It was at St. Basil’s House in London, the Fellowship’s home in those years, that he began to meet Christians in Britain and to exert a growing influence in ever-widening circles. Shortly afterwards Father Vladimir Theokritoff, the priest of the Russian Orthodox Patriarchal Parish in London died suddenly. Father Anthony was the obvious choice to succeed him.

In 1953 he was appointed hegoumen, in 1956 archimandrite, then in 1962 archbishop of the newly created Diocese of Sourozh, encompassing Britain and Ireland. (The name Sourozh comes from the ancient name of a city in the Crimea.) In 1963 he was named acting Exarch of the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia in Western Europe. By the time of his death, the Sourozh diocese had grown to twenty parishes.

Services in the London parish, which ultimately moved to the church which became All Saints Cathedral at Ennismore Gardens, not only met the spiritual needs of Russians living in or near London but attracted many people eager to experience Orthodox worship or seeking guidance in their own search for God. Many people who had no Russians in their family tree became Orthodox Christians thanks to his sermons, broadcasts and writings.

During the long years of Soviet rule, Metropolitan Anthony played an important part in keeping the faith alive in Russia through countless BBC World Service broadcasts. Perhaps still more important were the annual BBC broadcasts of the All-Night Paschal Vigil service at the London Cathedral. As Matins began, Metropolitan Anthony would emerge from behind the iconostasis to encourage the congregation, as they stood waiting in the dark, to speak up with their responses as this would be the only Paschal service that many in the Soviet Union would hear.

Beginning in the sixties, he was able to make occasional visits to Soviet Russia, where he not only preached in churches but spoke informally to hundreds of people who gathered in private apartments to meet him and engage in dialogue. Books based on his sermons were circulated in samizdat among Russian intellectuals until they could be openly published in the 1990s.

During the past decade, his declining health ruled out trips to Russia but he corresponded with many church members, stated his opinion on controversial issues of church life in letters to the Patriarch and the Councils of Bishops, and continued to preach his message of Christian love and freedom — not always welcome in the post-Communist Russian Church — through books and tapes.

One of the stories he sometimes told late in his life was about a letter he received from a monk in Russia who wrote there were “three great heretics” living in the west whose books were being read in Russia — Alexander Schmemann, John Meyendorff and Anthony Bloom. The letter writer asked the assistance of Metropolitan Anthony in finding out more about “this Anthony Bloom.”

For years Metropolitan Anthony was a familiar voice on British radio. The BBC had grave doubts when it was first proposed that he do English-language broadcasts. It was feared that the combination of his Russian-French accent and his refusal to use a script would lead to problems. But his transparent spiritual qualities and ability to speak fluently for a set number of minutes made him an instant success. At the height of his fame, Gerald Priestland, the renowned BBC religious correspondent, called him “the single most powerful Christian voice in the land.”

One of his most memorable broadcasts was a discussion with the atheist Marghanita Laski in which he said that her use of the word “belief” was misleading. “It gives an impression of something optional, which is within our power to choose or not … I know that God exists, and I’m puzzled to know how you can manage not to know.” (The transcript of their exchange is included in The Essence of Prayer.)

Outspoken on many issues, at times his plain speech landed him in hot water with the Moscow Patriarchate. In 1974 he was deprived of the position of Exarch for having written to The Times, in his name and that of the clergy and believers of the Sourozh Diocese, disowning criticism of Alexander Solzhenitsyn made by a senior hierarch in Moscow. Nevertheless, he remained head of his diocese. No attempt was made to prevent him continuing his visits to Russia.

His several books were widely read. Living Prayer, a best seller, has been translated into ten languages. It was later reprinted as a section of The Essence of Prayer.

In great demand as a speaker, Metropolitan Anthony spent much of his time preaching in non-Orthodox churches, leading retreats, giving talks and hearing confessions. He regularly spoke in hospitals, particularly about death, drawing on his experience as a cancer specialist. He received honorary doctorates from Cambridge and from the Moscow Theological Academy.

After the liberation of the Church in Russia, some priests and bishops proposed nominating him when elections for patriarch were held in 1990. But Metropolitan Anthony declined, citing his age. “If this had only happened ten years earlier, I might have agreed,” a relative quoted him as saying.

Earlier this year, Patriarch Alexy II, in an open letter, appointed Metropolitan Anthony to be in charge of a new Metropolia which, it was hoped, would embrace all Orthodox Christians of Russian tradition in Western Europe, and might eventually become the foundation for a Local Orthodox Church.

Citing age and poor health, Metropolitan Anthony had several times offered his resignation as head of the Sourozh Diocese but each time it was declined by the Moscow Patriarchate. Only five days before his death did the Holy Synod finally relieve him of his official duties, handing over to Bishop Basil (Osborne) of Sergievo the direction of the diocese.

Few bishops were more accessible to their flock, but this sometimes had comical results. When one parishioner rang to say that “Peter” had died and asked for prayers, Metropolitan Anthony immediately complied, then asked when the funeral would be. “Oh, there won’t be one,” he was told. “We flushed Peter down the loo.” Peter turned out to be a parakeet.

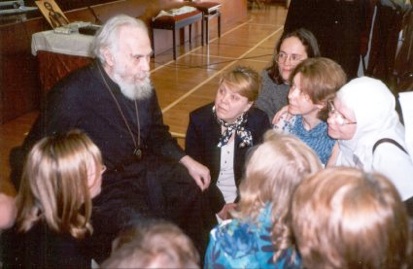

He was attentive to the person to whom he was listening, no matter who it was, to an astonishing degree. “In my life no one else had ever looked at me with such absolute attention,” people would often comment.

He loved going to children’s camps, allowing himself to be drilled and taking part in playlets, usually as a surgeon, dressed always in his monastic garb. “I always wear black when I operate,” he would say with a chuckle.

He would sometimes remark that he was quite prepared to be told he was a crackpot, but added, “Even if I am a crackpot, I’m a lot steadier and more normal than some people you might call normal. I’ve been a doctor and a priest without showing much sign of mental derangement.”

His faded and frayed black robe seemed nearly as old and worn as he was. Once, while visiting Russia, he was lectured by another monk who had no idea that this was the famous Metropolitan Anthony and was angry to see him awaiting their special guest from London in such tattered clothing. Metropolitan Anthony accepted the criticism meekly.

“He always seemed to me an actual witness of Christ’s resurrection,” said a regular participant in the annual Sourozh diocesan conference in Oxford, “not someone who believed it because he heard a report from a trustworthy source or read about it in a book, but someone who had seen the risen Christ with his own eyes. In meeting Metropolitan Anthony, I can understand why in the Church certain saints are given the title ‘Equal of the Apostles’.”