There is a situation in which we have no right to complain of the absence of God, because we are a great deal more absent than He ever is.

At the outset of learning to pray there is one very important problem: God seems to be absent. Obviously I am not speaking of a real absence—God is never really absent—but of the sense of absence which we have. We stand before God and we shout into an empty sky, out of which there is no reply. We turn in all directions and He is not to be found. What ought we to think of this situation?

First of all, it is very important to remember that prayer is an encounter and a relationship, a relationship which is deep, and this relationship cannot be forced either on us or on God. The fact that God can make Himself present or can leave us with the sense of His absence is part of this live and real relationship. If we could mechanically draw Him into an encounter, force Him to meet us, simply because we have chosen this moment to meet Him, there would be no relationship and no encounter. We can do that with an image, with the imagination, or with the various idols we can put in front of us instead of God; we can do nothing of the sort with the living God, any more than we can do it with a living person.

A relationship must begin and develop in mutual freedom. If you look at the relationship in terms of mutual relationship, you will see that God could complain about us a great deal more than we about Him. We complain that He does not make Himself present to us for the few minutes we reserve for Him, but what about the twenty-three and a half hours during which God may be knocking at our door and we answer, ‘I am busy, I am sorry,’ or when we do not answer at all because we do not even hear the knock at the door of our heart, of our minds, of our conscience, of our life. So there is a situation in which we have no right to complain of the absence of God, because we are a great deal more absent than He ever is.

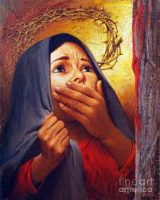

The second very important thing is that a meeting face to face with God is always a moment of judgment for us. We cannot meet God in prayer or in meditation or in contemplation and not be either saved or condemned. I do not mean this in major terms of eternal damnation or eternal salvation already given and received, but it is always a critical moment, a crisis. ‘Crisis’ comes from the Greek and means ‘judgment.’ To meet God face to face in prayer is a critical moment in our lives, and thanks be to Him that He does not always present Himself to us when we wish to meet Him, because we might not be able to endure such a meeting. Remember the many passages in Scripture in which we are told how bad it is to find oneself face to face with God, because God is power, God is truth, God is purity. Therefore, the first thought we ought to have when we do not tangibly perceive the divine presence, is a thought of gratitude. God is merciful; He does not come in an untimely way. He gives us a chance to judge ourselves, to understand, and not to come into His presence at a moment when it would mean condemnation.

Look at the various passages in the Gospel. People much greater than ourselves hesitated to receive Christ. Remember the centurion who asked Christ to heal his servant. Christ said, ‘I will come,’ but the centurion said, ‘No, don’t. Say a word and he will be healed.’ Do we do that? Do we turn to God and say, ‘Don’t make yourself tangibly, perceptively present before me. It is enough for You to say a word and I will be healed. It is enough for You to say a word and things will happen. I do not need more for the moment.’ Or take Peter in his boat after the great catch of fish, when he fell on his knees and said, ‘Leave me, O Lord, I am a sinner.’ He asked the Lord to leave his boat because he felt humble—and he felt humble because he had suddenly perceived the greatness of Jesus. Do we ever do that? When we read the Gospel and the image of Christ becomes compelling, glorious, when we pray and we become aware of the greatness, the holiness of God, do we ever say, ‘I am unworthy that He should come near me?’ Not to speak of all the occasions when we should be aware that He cannot come to us because we are not there to receive Him. We want something from Him, not Him at all. Is that a relationship? Do we behave in that way with our friends? Do we aim at what friendship can give us or is it the friend whom we love? Is this true with regard to the Lord?

Let us think of our prayers, yours and mine; think of the warmth, the depth and intensity of your prayer when it concerns someone you love or something which matters to your life. Then your heart is open, all your inner self is recollected in the prayer. Does it mean that God matters to you? No, it does not. It simply means that the subject matter of your prayer matters to you. For when you have made your passionate, deep, intense prayer concerning the person you love or the situation that worries you, and you turn to the next item, which does not matter so much—if you suddenly grow cold, what has changed? Has God grown cold? Has He gone? No, it means that all the elation, all the intensity in your prayer was not born of God’s presence, of your faith in Him, of your longing for Him, of your awareness of Him; it was born of nothing but your concern for him or her or it, not for God. It is we who make ourselves absent, it is we who grow cold the moment we are no longer concerned with God.

From Beginning to Pray by Met. Anthony of Sourozh (Bloom)