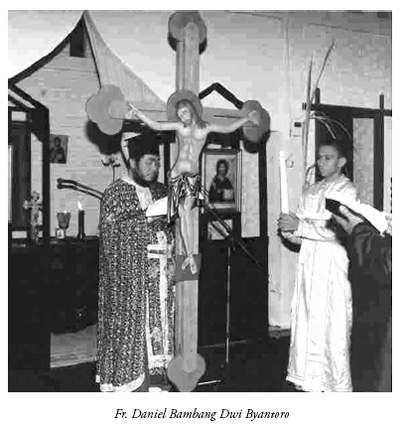

An Interview with Archimandrite Daniel Bambang Dwi Byantoro by Thomas Hulbert

When Archimandrite Daniel, the founder of the Orthodox Mission in Indonesia, came into the little bookstore in Amsterdam where we had arranged to meet, he was fresh off the plane from Jakarta, a flight of many long hours. Although he was tired, I could not persuade him to sit down; instead he inspected everything in the bookshop, visibly taking great joy in small things. Father Daniel’s incredible journey from Islam to Orthodoxy has taken him from Indonesia to Korea, Mt. Athos, the United States and Europe. The very idea of traditional Christianity in Indonesia, long a Moslem-dominated country, brings up clashing images – the colorful southeast Asian culture watered for centuries with devout Islamic practices, now nurturing the struggling seed of Orthodoxy. Indeed, Fr. Daniel’s own story is like one out of the Gospel itself, its disparate elements reaching harmony in Christ.

I had imagined that he would be a tall, emaciated ascetic, whose doctoral education and theological studies would make me strain to follow his thought. Instead he is short and round with an angelic face wide enough to contain his almost continual smile and a wisp of a beard that reminded me of an Oriental sage. I was immediately disarmed by his down-to-earth accessibility – he took off his shoes and put them by the door, and we promptly sat down to lunch. We had not been together more than a few moments before I felt that a good friend had come to visit after a long journey. Soon, a different side of him appeared, the ceaseless activity of a missionary. He made telephone calls in a variety of languages, quickly prepared his bags for the next phase of his journey, and checked his e-mail for missionary correspondence. It too was varied: leaders of various Christian groups asking for information on Orthodoxy, meetings to be arranged, requests for pastoral counseling, and, of course, news about the current frightening persecution of Christians in Indonesia. Yet he never lost his childlike brightness and relaxed manner.

Thomas: How do you approach the souls that come to you? If they are Moslem how do you work with them and how do you explain the difference between Christianity and Islam. How do you draw them in?

Fr. Daniel: I think that in any missionary work, you must first of all understand the culture of the people and you have to be able to speak within the bounds of that cultural language, because otherwise your word cannot be heard or understood. So, when you talk with a Moslem, you must understand the Moslem mind. Don’t just try to throw in words and phrases that are familiar to Christians, to Orthodox, because they will not be understood by a Moslem. First of all, when you talk to a Moslem, you have to emphasize that God is One.

Thomas: Because they already believe this?

Fr. Daniel: Not only because they already believe this, but because they accuse us [the Christians] of having three gods. That is the problem. So, you have to clear up the misunderstanding that we worship three gods. Don’t try to use our traditional language, like Father, Son and Holy Spirit – because for them, that is three gods! In their minds, the Father is different, the Son is different, the Holy Spirit is different. For myself, I emphasize that God is One, that this One God is also the Living God, and as the Living God He has Mind. Because if God didn’t have a mind, I’m sorry to say, He would be like an idiot. God has to have a mind. Within the Mind of God there is the Word. Thus, the Word of God is contained within God Himself. So, God in His Word is not two, but one. God is full with His own Word; He is pregnant with Word.

And that Word of God is then revealed to man. The thing that is contained within – like being impregnated within oneself – when it is revealed, it is called being born out of that person. That is why the Word of God is called the Son: He is the Child Who is born from within God, but outside time. So, that is why this One God is called the Father, because He has His own Word Who is born out of Him, and is called the Son. So, Father and Son are not two gods. The Father is One God, the Son is that Word of God. The Moslem believes that God created the world through the Word. So what the Moslem believes in as Word, is what the Christians call the Son! In that way, we can explain to them that God does not have a son separate from Himself.

Thomas: So the Moslems see our idea of the Son of God in terms of physical sonship.

Fr. Daniel: Yes, of course. And God does not have a son in that way, that’s true. He is not begetting in the sense of a human being giving birth. He is called the Father because He produces from Himself, His own Word, and that Word is the Son. So because God is the living God, He must have the principle of life within Himself. In man, this principle of life is man’s spirit. God is the same. The principle of life within God is the Spirit of God. It is called the Holy Spirit. But the Holy Spirit is not the name of the Angel Gabriel, as the Moslems understand it. The Holy Spirit is the living principle, the principle of life and power within God Himself. This One God is called the Father because He produced from Himself His own Word, which is called the Son, and the Word of God is called the Son because He is born out of the Father eternally, without beginning, without end. This One Living God also has Spirit within Himself. So, Father, Son and Holy Spirit is one God. This is the way we explain to Moslems about the Trinity, and we should not try to use our language of “Father and Son, co-equal, co-…” something like that. Even though it is our Christian terminology, they will not understand this. The purpose is not to theologize to them but to explain the reality of the Gospel in a way that is understandable to them. This is point number one: you have to be clear about the Trinity. The second point is this: the basic difference between Islam and Christianity concerns revelation. In Islam, God does not reveal Himself. God only sends down His word. “Revelation” in Islam means “the sending down of the word of God” through the prophets. And that word is then written down and becomes scripture. So in Islam, revelation means the “inscripturization” of the word of God while in Christianity, it is not the same. The Word was sent down to the womb of the Virgin Mary, took flesh and became man. Namely, Jesus Christ.

So, the two religions believe that God communicated Himself to man by means of the Word, but the difference is how that Word manifested in the world. In Christianity it is manifested in the person of Jesus Christ and in Islam it is manifested in the form of a book, the Koran. So, the place of Mohammed in Islam is parallel to the place of the Virgin Mary in Orthodox Christianity. That is why in Islam the Moslems respect Mohammed, not as a god, but as the bearer of revelations. Just as the Orthodox Church respects the Virgin Mary not as a goddess but as the bearer of the Word of God, who gave birth to the Word of God. Incidentally, the two religions both give salutations, to Mohammed for the Moslems and to the Virgin Mary for Christians. The Moslems also have a kind of akathist, like a paraclesis but to Mohammed! It is called the depa abarjanji – in Orthodox terms it would be a “canon” to Mohammed, because he is the bearer of the revelation. Road to Emmaus Vol. 2, No. 3 (#6) 6

Thomas: So Mohammed is venerated like a saint?

Fr. Daniel: He is venerated, yes. Very much so. But there are also the Sufi Moslems, who sometimes believe that Mohammed was “already there,” like the Arian misunderstanding of Christ. In their view, Mohammed was the “first created soul,” for whom the world was created. This is called the Nor- Mohammed. So, the purpose of Islamic mystics is to be like Mohammed, to imitate him.

Thomas: To be the bearer of the Word?

Fr. Daniel: As Mohammed was.

Thomas: So, that is why Sufi mystics are perhaps not so legalistic?

Fr. Daniel: Yes, they are more mystical. So, for us, the image of the Church is the Virgin Mary. We are called to be like the Virgin Mary in our submission to God. The Virgin Mary is the picture, the image, or I should say, the icon of the Church. Mohammed is the “icon” of the ideal Moslem man, and because of that the way we worship diverges. In Christianity, because the Word became a man, became flesh, for us to be united with that Word we have to be united with the content of that revelation. What is the content? The incarnation, crucifixion, death and resurrection of that Person. In order for us to be united with the content of that revelation, we have to be united in that Person, namely in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. How? Through baptism. And we also have to be united with the life of the resurrection of that incarnate Word. How? By the Holy Spirit, through Chrismation. So, the sacraments are very important for us because God became man. He sanctified the physical world so that the physical elements of nature can be used as the means by which we are united with the person of Christ in the sacraments.

In Islam, however, because the word becomes a book, the content of the book is writing. It is not flesh. So, that is why in order for a Moslem to unite with the content of the two-fold revelation (that God is one and that Mohammed is His prophet) one has to recite the source of revelation – because it is a book. But you cannot be united with or immersed in a book, you can only memorize the content of the book in the original form, namely in Arabic. So, Arabic scripture is the form of that revelation. The God-Man Jesus is the form of that revelation in Christianity. In order for a person to be initiated into Islamic revelation, you must confess the creed: “I confess that there is no God except Allah, and that Mohammed is the Apostle of Allah.” When you confess that, you become Moslem. There is no baptism, you are not united in the death of anyone, you are only united to the form of the revelation. To stay united to the revelation, you must keep the prayers. In prayer you recite the Koran, so five times a day you pray, five times a day you immerse yourself in the ocean of divine revelation, which is the Koran. Prayer itself is the sacrament of Islam. In order for us Christians to be immersed in the form of the revelation, which is Jesus Christ, we have to partake of the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ continually. In that way we are united to Jesus Christ, while in Islam the recitation of the Koran is the most important thing, because it is a form of sacrament to the Moslems. So those are the basic differences. This is a way to understand the Moslem mind instead of just arguing against them.

Thomas: Would you say that most Muslims are conscious of this theological aspect of God and man’s relationship to Him?

Fr. Daniel: Yes, of course, through the Koran, through the prophets. Thomas: In Islam, is a person’s manner of life of secondary importance to the correct understanding of the form of revelation?

Fr. Daniel: In the manner of life, Islam refers again to the form of revelation, which is a book. The content of the book is writing, the writing is law, so the law has to be obeyed. If we have the imitation of Christ and His teachings, they have the imitation of Mohammed and the Koran. That is why the life of a Moslem is dictated and governed by the law of the Koran, while our life is dictated by the law of Christ in the Holy Spirit. Thomas: What is the difference then between following these two laws?

Fr. Daniel: In Islam, there is no new birth, just a return to God, which means repentance. This is called submission to God.

Thomas: And that is the meaning of the word Islam, “to submit?”

Fr. Daniel: Yes. Islam means submission to God. That is the way we have to understand the difference between the way of life of Islam and of Orthodox Christianity. There are some parallel ways of thinking, but very different content. The main difference is that in Orthodox Christianity the Word became flesh and in Islam the word became a book. That is the main difference.

Thomas: How do Moslem converts to Orthodoxy sustain their belief in the predominantly Moslem society of Indonesia? Do you have communities of Orthodox Christians who live together and support each other in the hostile religious environment, or is the parish way of life more common?

Fr. Daniel: No, we don’t really have any special kind of community where we live together. We are spread out geographically like other Christians, and we come to the church for services. But as to how we withstand the environment – the way I do it is that I teach very strong Bible classes in Indonesian. Every day I have Bible study before Holy Communion. In between Orthos [Matins] and Liturgy there is always Bible study. And in my Bible study, there is always a comparison between Christianity and Islam, all the time. It reminds people that this is Christianity and this over here is Islam. For example, I ask questions like: “OK, in nature which is higher, a human being or a book?” Being formed by Moslem culture, some of them say “a book.” So then I’ll ask them, “Which is higher, then, revelation of God in the form of a human being or in the form of a book?” Of course, revelation is higher in the form of a human being. They can see that from God Himself. So, God the Word become flesh, the Word become man, is higher than the word which became a book. That’s number one. Second, if in the past God sent down His word through the prophets in the form of a book, namely the Old Testament, and the Old Testament has been fulfilled completely in the form of man, Jesus Christ, is it possible, after the Word of God has been fulfilled in man, that God would revert to the old way, sending a book again? Of course not! When the Word has become man, it is already complete. And that Man, Jesus Christ, is still alive! So, it is impossible that God would again send another revelation 9 Orthodoxy in Indonesia in the form of a book. From our point of understanding, it is not possible. For us, the most perfect prophet and the last revelation of God is Jesus Christ. There is no need for any other revelation. This is the point I emphasize again and again. They understand this quite well. So this is how we keep holding onto the path of Christ in spite of so many attacks from the Moslems.

Thomas: The Moslems pressure the Christians, then, knowing that they can tempt them with these deeply-rooted cultural ideas?

Fr. Daniel: Yes.

Thomas: Maybe you could tell us more about this. What are the difficulties that Christians encounter in a Moslem environment?

Fr. Daniel: You know, when you are living among a Moslem majority, sometimes you are afraid of being asked about your faith. Christian people who have been formed in a Moslem environment cannot always explain themselves; and Moslems, fearing that Christian “heresies” will spread are always ready to attack – about the “three Gods,” about “worshiping a human being,” about the cross, about all the fundamental beliefs of Christianity. Christians are often not ready to answer these things. Also, almost every morning all of the Indonesian TV channels broadcast about Islam. There is no other religion being aired. Everyone is bombarded with Islam, the mosques are plastered with loud speakers and people are always talking against Christianity. The police do not do anything. In this way, we have been psychologically defeated. Many books are written attacking Christianity and there is no way to answer them because when a Christian tries to answer about his faith he has to criticize Islam and this is very difficult. There will be a reactionary demonstration against him. In the city of Solo, there is a man by the name of Achmed Wilson who became a Christian. He is now on trial in court because he was asked on a call-in radio program what he thought about Mohammed, and he answered that he believed as a Christian. So, this is a great problem for him now. Things like this are very common.

Thomas: So there is no real religious freedom?

Fr. Daniel: No. Don’t even think about it. It is very difficult when you live in such a society. You are allowed to criticize the idea of God because god is a general term. The Buddhists believe in a god, the Hindus believe in a god, the Christians believe in a god, but don’t criticize Mohammed because that is distinctly Islamic. You can criticize the idea of God, you can become an atheist, but don’t say anything about Mohammed or you’ll be in trouble.

Thomas: How do former Moslems who convert to Orthodoxy cope with family situations? Are they able to continue to live with their non-Christian family members? Are they accepted?

Fr. Daniel: Some of them are accepted and some are not. There are cases when they return to their former beliefs, to their families, and confess Islam again, although when they meet me they still say that they believe in Christ. They do believe and they worship secretly in their homes, but they cannot come to church. Several of our people are like that. Some of the families are better. They are more open and they let their children continue in their Christian faith without being disturbed. It differs with each person, from area to area, and even from one ethnic group to another. Some ethnic groups are more fanatical than others.

Thomas: How do you encourage Orthodox Christians to conduct themselves in public given this dangerous environment? We here in Europe often read about persecution and martyrdom in Indonesia.

Fr. Daniel: I always teach them that if there is no possible way to escape (even if we have been trying to be good and obey the laws of society), if we become known as a believer, if they stigmatize us as unbelievers as heretics or whatever, then it is obvious there is no other way – if martyrdom comes, then we have to accept it. If you cannot escape being a martyr, do it! Go for it! I teach this in church, and I say, even to myself, that there is no other way. But still, we do not try to provoke other people. Even if we evangelize, we evangelize nicely, explaining our faith like: “this is your faith and this is our faith.” We do not degrade other people’s beliefs.

Thomas: How would you encourage Christians to look at Moslems? There are two tendencies in the West: either to unconcernedly accept Islamic people and ideas regardless of their growing numbers and cultural and religious influence; or to see them as bogey men responsible for many of the world’s current political problems. Of course, we know that as individuals there are many wonderful individual Moslem people who are charitable and generous to their neighbors regardless of creed, but for many of us the overall influence of modern Islam, particularly on Christian populations, is a question. We do not want to be naive on one hand, nor uncharitable on the other. Do you have any thoughts on this?

Fr. Daniel: It is a difficult problem indeed, even for us, because there is always a dialectical relationship between us and them. In Indonesia, because they are the majority, we have to befriend them, there is no other choice. Individually, we must treat them as anyone should be treated – with love. But theologically we have to stand on what we believe to be true, there can be no compromise.

Thomas: What do you see for the future of Orthodoxy in Indonesia?

Fr. Daniel: I cannot see into the future but I believe that Orthodoxy will continue to grow. It depends on more people receiving an Orthodox education – the more the better. Right now in Indonesia, Orthodoxy is still identified with myself. When people think of Orthodoxy they think of me. We need to have more young people educated. Sometimes people do not understand this – but I try my best. I try to send as many people as possible to Russia, to Greece, but I am not a bishop so I don’t have the power to arrange things so easily. If I become a bishop, I will send as many people as possible abroad to gain experience and education in Orthodoxy, so that when I die, someone can continue the work. This is the main point.

Thomas: Do you think that there is a likelihood of the Orthodox in Indonesia acquiring their own bishop?

Fr. Daniel: I don’t know. I can’t say anything.

Thomas: How is the Indonesian Orthodox community structured?

Fr. Daniel: We have two levels of structure, actually, because the Orthodox Church is recognized outwardly as being under the State Department of Religion, as part of the Protestant contingent. This is because there are five recognized religions in Indonesia: Roman Catholic, Protestant, Islam, of course, Hindu and Buddhist. We have to fit somewhere within these five categories, so we fall under the Protestants. In terms of our relationship with the government, we have our own leader. I appoint a lay person who is responsible to me. Within the Church, we are directly responsible to the Archbishop of Hong Kong, who is under the Patriarch of Constantinople. On the parish level, we have a council with a president and I am the, ah…, I don’t know what I am! (laughs) There is the president of the parish council and I am the priest there… the proistamenos, who directs the president. There is also a vice president, a secretary, a treasurer and such. We also have organized religious education, and a youth organization, called Hanna Arhim in Hebrew. We use a Hebrew title to show the Moslems that we are also Semitic,* we are not Western. So we use a lot of Hebrew expressions in presenting ourselves to the outside, rather than Arabic, because Arabic is sometimes seen as imitating Islam. We have a women’s association called Saint Sophia, a priests’ association, and other things like that.

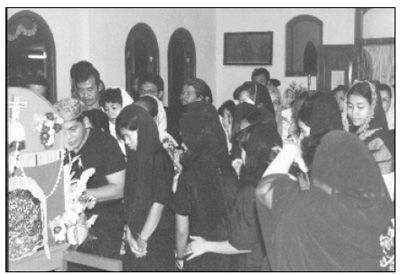

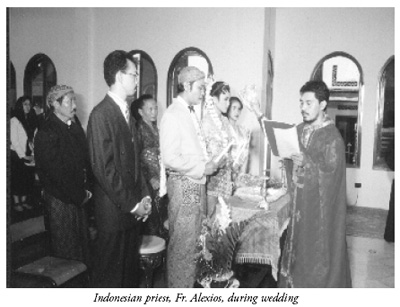

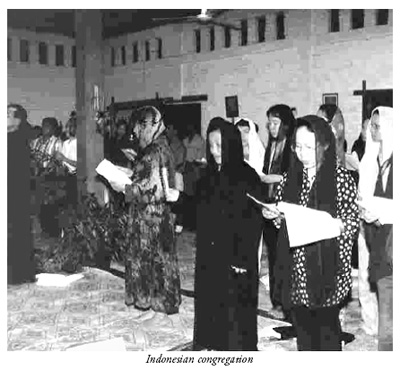

Thomas: How does Orthodoxy in Indonesia differ in tone or custom from the West? What is it like in your churches?

Fr. Daniel: Of course it is different, first of all because we are not Western people, we are Asian. So, we express our faith in an Asian way. We do not sit in chairs, we sit on the floor on a mat. We put off our shoes when we enter the church, women wear the kafer [traditional Indonesian garb] and a veil. We have adapted some other cultural expressions, like in the wedding ceremony where we use our traditional Indonesian attire. We do not use koliva for the dead, for instance, because we do not eat wheat – it is difficult to find! We use rice. We make use of what we have. It’s very Indonesian, very Asian. So, the Orthodox Church in Indonesia is more eastern than in Greece or Russia or Europe! We can’t be afraid for Orthodoxy to take on local forms.

Thomas: Can we use this as a measure of the depth of penetration of Orthodoxy into a culture?

Fr. Daniel: Yes. The content is visible in the form. That also goes for people converted to Orthodoxy in the Greek or Russian traditions who are themselves not Greek or Russian. Thomas: Does the Indonesian Orthodox community have services in Indonesian or in Greek?

Fr. Daniel: Of course, in Indonesian. Thomas: What about other languages?

Fr. Daniel: Sometimes if we have guests, here and there we have something in Greek or English. Sometimes even in Russian.

Thomas: Indonesian remains the main liturgical language then, one that all the different ethnic groups in Indonesia speak?

Fr. Daniel: Yes. I have translated the services into Indonesian for this purpose. Thomas: Generally, I don’t think that Western people know how varied the languages and cultures are in Indonesia.

Fr. Daniel: We have … different languages and dialects in Indonesia, with one national language. I have translated the service books into Indonesian, and now I’m beginning to translate them into Javanese, which is my ethnic language. The services are also in the Patlak language, which is spoken on Sumatra and there are plans for translation into the Balinese language, spoken on the island of Bali. This is going slowly. Thomas: So local parishes will be able to celebrate in their own language?

Fr. Daniel: Yes. And if there is a need, they can always celebrate in Indonesian. Thomas: A more personal question for you. What are the greatest temptations in your work?

Fr. Daniel: (Laughs) To leave it because it is too difficult. I know that I have my talent, and that I can always teach. Sometimes I just want to go be a professor at the university. Again and again, God has helped me to stay where I am, to remember my calling. It is difficult because I have a lot of responsibility to pay for this or that, to help young people begin theological study at the university. I must pay for these things every month. I think I have more responsibilities than people who have their own children! Thomas: What is your greatest sorrow?

Fr. Daniel: My greatest sorrow . . .when I’m trying to do my best, and I am accused of things that I did not do. Thomas: And your greatest joy?

Fr. Daniel: The greatest joy is when someone is converted to Orthodoxy. Thomas: Who are the saints who have helped you, the ones you feel closest to?

Fr. Daniel: My own patron saint, St. Daniel the Prophet. I chose that name because I believe that he had such a strong heart. He had courage against the king and the lions; and I am living among the lions, let me tell you. I want to have his courage.

Thomas: Being a Semitic-oriented people and having less exposure to the saints of traditional Orthodox lands, would you say that Indonesian Orthodox are more drawn to the Old Testament saints?

Fr. Daniel: Prophet Daniel was my choice, not for Indonesians in general. I encourage people to be close to their own particular saints. For the time being, the spiritual orientation of the Indonesian people is not so much in the direction of the saints as it is to the Holy Scripture itself. This is still the foundation. Thomas: The traditional orientation reflects a more Islamic pattern with a Christian substance?

Fr. Daniel: Yes. I’m speaking here not of the belief but of the pattern. One has to introduce things slowly. There is less emphasis on the saints, although the Orthodox, of course, believe in them and they have their names. In our cultural traditions we also have an understanding of sacred places, especially graveyards, the burial place of local saintly figures. This is not strange to us, it is not new to our culture. But I’m afraid that new converts look at the saints in their old way of understanding – the dead people in their past, the worship of ancestors. This is a concern here, as it is in a lot of native cultures. So, I try to emphasize more the understanding of Scripture in the light of Orthodox belief.

Thomas: As someone who has traveled extensively and seen Orthodoxy in many places, do you have a word for people in the West? What can we do to deepen our faith?

Fr. Daniel: As Westerners, to deepen your faith you must go back and explore the original Western culture that was sanctified by Orthodoxy, the Christian society that was oriented towards God. These are your roots. From there, try to sanctify the culture you are in. Don’t let yourselves be eroded by contemporary Western culture, which is very shallow. Also, try to be true to the Faith as such, don’t try to “revise” it according to the mode of the time. If you do not keep the Faith as it is, you will be undone by your surroundings. Try to interpret your life within the context of your faith. When people do not have culture, they do not have a root – when they do not have a root, they are shallow. If Orthodoxy is only understood superficially, outside of the context of its historical rootedness, then we also become shallow – it is just a fad, like any “new” religion. We have to be able to identify ourselves with the whole flow of history within the Church. I think that it is very important to acquire our identity within the Church.

Thomas: So that means going “against the flow” because Western cultures are for the most part losing their Christian world-view.

Fr. Daniel: Of course. It is difficult, but the Lord went against the flow, didn’t He? Yes, He did.

Thomas: In our age of electronic communication, how can Orthodoxy adapt to a technological society and yet not partake of its aimlessness?

Fr. Daniel: Use the means available as a vehicle. Use the Internet as much as possible for preaching Orthodoxy, use television as much as possible to reach people. This is better than just letting the Hindu gurus or whoever take it over. Why shouldn’t we make use of it? We waste a lot of opportunity if we don’t.

Thomas: Do you think there is a boundary, past which Orthodoxy shouldn’t integrate with the media?

Fr. Daniel: Yes, when we interpret our lives in terms of that media. But when we use this tool and fill it with a new meaning, the Orthodox Christian worldview, then it becomes an instrument for Orthodoxy. Thomas: One more question about intercultural relationships. Many of us know little more about Asian spirituality than the contemporary popular presentation of “Eastern religions” that has torn many Westerners from their roots, and substituted a blend of pseudo-mysticism and esoteric dead ends. What of real spiritual value can the West learn from the East?

Fr. Daniel: A lot. A major lesson is the steadfastness of the Eastern people in their religiosity. The Eastern people are very religious in many ways, and it is very strange for Indonesians to hear from Western people that they don’t believe in God. It is very strange for us, because for us Asian people, God is so obvious. How can anyone not believe in Him? The grandeur of nature and everything right before you? How is it possible?! So, if you deny Him, you are left with only your own small mind, and you are very limited. But, that you cannot see the Hand of the Maker behind the grandeur of nature! It is difficult for me especially to understand this Western way of thinking. I understand much through reading and my travels, but still, it is strange that people cannot believe in God. I think this is not only a matter of mind, but a matter of heart. The heart becomes callous. For Eastern people, the reference is immediately to God. Either to God or to gods, but still, the reference point is spiritual.

Thomas: Is there anything else that you would like to say, any message to the people reading this interview?

Fr. Daniel: I want to encourage Orthodox people all over the world to feel the unity of Orthodoxy. It is evil that Orthodoxy is so divided along the line of cultures and ethnicity. I want to see the Orthodox feel a oneness: when the Orthodox people in Greece, or Russia, or Indonesia, hearing of the suffering of others, can feel and say, “This my brother.” None of this, “You are Greek and I am Russian,” or, “I’m sorry, I’m Indonesian.” What kind of Orthodoxy is this? It’s not catholic, not universal. The compartmentalization of Orthodoxy is not Orthodoxy.

Thomas: This division is even more visible as our world comes closer together.

Fr. Daniel: Yes. The second thing I would like to say is that I want Orthodox people to be enthusiastic about their faith. To preach the Gospel – to preach it and not just keep it close and say, “This is mine, my culture.” Also, when you preach Orthodoxy, don’t preach your particular expression of Orthodoxy – that someone has to be Greek or Russian. Orthodoxy is not Greek or Russian; it is universal and for everyone. If you become Orthodox, do not associate yourself primarily with being Greek or Russian – associate yourself with the Church. This is the way it has to be. When I converted to Orthodoxy in Korea, I did not associate Orthodoxy with any particular culture, I associated Orthodoxy with the whole history of the Church. Orthodoxy has the responsibility to come out of its own cocoon, to tell the world, “Here we are!”

Thomas: Don’t you think that our own time is especially good for this because we are being forced together into a so-called “global village?”

Fr. Daniel: I think so, yes. But then again, I believe that among all the Orthodox ethnic groups, there have always been people who have understood this, and these people now have to take the lead in bringing Orthodox people together across ethnic and cultural lines. If not, the new Orthodox Churches in Asia and in Africa will be very troubled. Speaking as an Asian, we don’t want a new kind of colonialism. I want to warn the people from Western countries who are Orthodox and who want to do missionary work in Asia or in Africa – do not try to impose your own brand of spiritual colonialism. We have had a long history of colonialism and we will resist it. If traditional culture is suppressed and if there is a lack of recognition of local leadership, the native Christians will eventually revolt. This is no longer the time of “You are lower than us, we are white, therefore we are better than you.” No, no, there is no time for this. Truly, there has never been a time or place for this, because we are all human beings created equally in the Image of God. That is why we have to value the culture, value the local people and recognize their talent and potential. It is like this.

Thomas Hulbert is the Western European correspondent for Road to Emmaus