One of the obvious differences between the Orthodox and Western understanding of marriage is that in the West, marriage is what two people do, while in the East, it is something that is done to them. This difference is expressed in the wedding service. In the West, the two people give a set of vows, thus entering into a contract with each other. In the Orthodox service, no vows are exchanged; after the initial inquiry as to whether they want to be married to each other (more on that later), they say absolutely nothing. They also do nothing: something is done to them–crowns are placed on their heads, they are led by the priest around the gospel stand, the common cup is given to them, even their wedding rings are placed on their fingers by other people. Whatever the historical development of the Orthodox rite may have been, its form points to the belief in the sacramental nature of marriage. In this way, the rite of marriage similar to the Eucharist. One does not produce the Body and Blood of Christ the way that one would negotiate and produce a contract. All of the actions of the priest and the congregation are not aimed at the production of the Gifts, but at preparing their own hearts and souls for receiving the sacrament.

But when we speak of the sacramental nature of marriage, I think that we have mean some specific thing. Marriage is not a sacrament because it is listed as such in the catechism; and it is not a sacrament because God blesses the couple in some general way. One of the ways we can define a sacrament to be more precise for the purposes of this study is to look at it as transformation: it is not quantitative (whereby vows, blessings, certificates, etc. are added to the couple) but qualitative–the couple does not remain the same two people they were before the weddings but is transformed (“changing them by Your Holy Spirit” in the Eucharistic sense) into something they were not–a specific icon of Christ and His Church.

Just saying this, however, does not make it so. Many–if not most!–of our Orthodox marriages do not resemble the icon of Christ and look very similar to whatever model of marriage that our current society presents. If our theology is not having any practical effect in the actual marriages, then we must strive harder to make theology relevant to the lives of Orthodox spouses. The sacramental nature of an Orthodox marriage and the real presence of God as the third Person in the “trinity” of God, man and woman, needs to be made real in order to help move toward the sacramental transformation of the spouses.

One way to do that is to shift focus from marriage being an arrangement where I receive, into an arrangement where I give. I think that the modern understanding of marriage is a means by which people gain things: love, companionship, children, etc. We could present a model which focuses on the giving, the “emptying” of self. (This would probably help make Orthodox marriages stronger.) The Orthodox model for marriage could begin with the vision of marriage as a witness (martyria) to Christ’s self-sacrifice. In fact, when we speak of marriage being an icon of Christ and His Church, perhaps, we could clarify that it is specifically the self-sacrificial love of Christ that should be reflected through marriage. And just as a ‘Orthodox heritage club’ is transformed into the Church by the Eucharistic presence and action of the Holy Spirit, the married couple is no longer just a socio-economic unit or an instrument of reproduction but a “small Church,” the Body of Christ, His image in and to the world.

One thing which may be interesting in this context is that the question about the free and unconstrained will that is asked in the beginning of the marriage service. It would seem that historically, there was no “free and unconstrained” mutual consent in most Christian marriages. In Russia, marriages were arranged by the parents. I imagine that mutual attraction may have been a factor in some marriages, but “freedom to marry” did not exist as an institution until very recently. Even nowadays, various circumstances–from an unplanned pregnancy to economic consideration–place constraints on people’s decisions to marry. So, if the words about the free and unconstrained will truly mean an absolute freedom and a complete lack of constraints, then few marriages rise to this standard, or the words must mean something different–not what we think of initially. Perhaps, at that moment, the free will is “created”–a person makes a choice to say “I do.” In other words, the question is not so much asking whether the couple came to the temple under a complete lack of constraints, but whether they are willing to put their free and unconstrained will into this relationship from this point forward. This is not a meaningless choice, since on the other side is a rejection. In other words, what is happening will be happening regardless of whether the two people consent or not–the wedding will take place. But it is within the couple’s power to make the marriage work. And even though the context of the wedding service seems to suggest otherwise at first glance, this very act of putting human will into the service is a necessary intrinsic element of the sacrament. Elsewhere, I have written about a distinction between miracle, works of man, and sacraments. When God acts alone, it is a miracle; when man acts alone, it is works of man; when the wills and acts of God and man intersect, it is a sacrament. The “free and unconstrained will” of the human participants, then, is necessary in order for marriage to be a sacrament. And it cannot be some general will to marry, it has to be specific and immediate–the will to take this person whom you see here before you as your spouse. Again, there is a Eucharistic parallel to this mystery: man cannot become the Body of Christ; God cannot turn man into the Body of Christ against man’s will; only at the intersection of God’s will and man’s will the sacrament of the Body happens.

On the other hand, I also have to pause and ask what exactly the two people are consenting to or willing to do? It is certainly not the matter of living together or having babies–people have been doing that without the Church’s blessing for thousands of years. So, when we speak of marriage as an icon of Christ and His Church, it is not the image of cohabitation or procreation but of martyrdom. The crowning, the central element of the service, really only has one meaning–the bestowal of the martyr’s crowns. The real question to which the spouses respond, “I do,” is not whether they want to live together and make babies, but whether they are accepting the cross and making the sacrifice: “Do you have the free and unconstrained will to give your life for this person whom you see here before you? No lists of vows or contracts with small print to negotiate, because when you give away your life, you give it all and you lose it all, expecting no barter, or deal, or benefit in return.”

I think that this is the only way that the question about the free will makes sense. Marriage may be pre-arranged or the decision is constrained in some way–and this is acceptable, but the self-sacrifice in the image of Christ is a free choice, just like His.

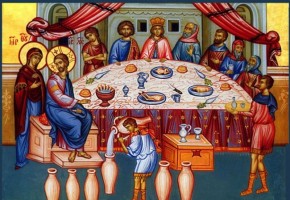

How is this concept expressed liturgically? I think that the connection between wedding rites and the Eucharist is not a mistake–it makes intuitive sense, even if it lacks historicity. Thus, ideally, every Liturgy should point to Christ’s sacrifice to us and compel us to reflect this image back to our spouses and to the world. And when Christ’s self-sacrifice is realized as the model for our marriages, the Eucharist becomes the liturgical expression of answering “I do,” which then transforms that brief moment at the beginning of the wedding service from something temporal and not altogether memorable into something which is connected to the timelessness of the Eucharist.

One of the obvious differences between the Orthodox and Western understanding of marriage is that in the West, marriage is what two people do, while in the East, it is something that is done to them. This difference is expressed in the wedding service. In the West, the two people give a set of vows, thus entering into a contract with each other. In the Orthodox service, no vows are exchanged; after the initial inquiry as to whether they want to be married to each other (more on that later), they say absolutely nothing. They also do nothing: something is done to them–crowns are placed on their heads, they are led by the priest around the gospel stand, the common cup is given to them, even their wedding rings are placed on their fingers by other people. Whatever the historical development of the Orthodox rite may have been, its form points to the belief in the sacramental nature of marriage. In this way, the rite of marriage similar to the Eucharist. One does not produce the Body and Blood of Christ the way that one would negotiate and produce a contract. All of the actions of the priest and the congregation are not aimed at the production of the Gifts, but at preparing their own hearts and souls for receiving the sacrament.

But when we speak of the sacramental nature of marriage, I think that we have mean some specific thing. Marriage is not a sacrament because it is listed as such in the catechism; and it is not a sacrament because God blesses the couple in some general way. One of the ways we can define a sacrament to be more precise for the purposes of this study is to look at it as transformation: it is not quantitative (whereby vows, blessings, certificates, etc. are added to the couple) but qualitative–the couple does not remain the same two people they were before the weddings but is transformed (“changing them by Your Holy Spirit” in the Eucharistic sense) into something they were not–a specific icon of Christ and His Church.

Just saying this, however, does not make it so. Many–if not most!–of our Orthodox marriages do not resemble the icon of Christ and look very similar to whatever model of marriage that our current society presents. If our theology is not having any practical effect in the actual marriages, then we must strive harder to make theology relevant to the lives of Orthodox spouses. The sacramental nature of an Orthodox marriage and the real presence of God as the third Person in the “trinity” of God, man and woman, needs to be made real in order to help move toward the sacramental transformation of the spouses.

One way to do that is to shift focus from marriage being an arrangement where I receive, into an arrangement where I give. I think that the modern understanding of marriage is a means by which people gain things: love, companionship, children, etc. We could present a model which focuses on the giving, the “emptying” of self. (This would probably help make Orthodox marriages stronger.) The Orthodox model for marriage could begin with the vision of marriage as a witness (martyria) to Christ’s self-sacrifice. In fact, when we speak of marriage being an icon of Christ and His Church, perhaps, we could clarify that it is specifically the self-sacrificial love of Christ that should be reflected through marriage. And just as a ‘Orthodox heritage club’ is transformed into the Church by the Eucharistic presence and action of the Holy Spirit, the married couple is no longer just a socio-economic unit or an instrument of reproduction but a “small Church,” the Body of Christ, His image in and to the world.

One thing which may be interesting in this context is that the question about the free and unconstrained will that is asked in the beginning of the marriage service. It would seem that historically, there was no “free and unconstrained” mutual consent in most Christian marriages. In Russia, marriages were arranged by the parents. I imagine that mutual attraction may have been a factor in some marriages, but “freedom to marry” did not exist as an institution until very recently. Even nowadays, various circumstances–from an unplanned pregnancy to economic consideration–place constraints on people’s decisions to marry. So, if the words about the free and unconstrained will truly mean an absolute freedom and a complete lack of constraints, then few marriages rise to this standard, or the words must mean something different–not what we think of initially. Perhaps, at that moment, the free will is “created”–a person makes a choice to say “I do.” In other words, the question is not so much asking whether the couple came to the temple under a complete lack of constraints, but whether they are willing to put their free and unconstrained will into this relationship from this point forward. This is not a meaningless choice, since on the other side is a rejection. In other words, what is happening will be happening regardless of whether the two people consent or not–the wedding will take place. But it is within the couple’s power to make the marriage work. And even though the context of the wedding service seems to suggest otherwise at first glance, this very act of putting human will into the service is a necessary intrinsic element of the sacrament. Elsewhere, I have written about a distinction between miracle, works of man, and sacraments. When God acts alone, it is a miracle; when man acts alone, it is works of man; when the wills and acts of God and man intersect, it is a sacrament. The “free and unconstrained will” of the human participants, then, is necessary in order for marriage to be a sacrament. And it cannot be some general will to marry, it has to be specific and immediate–the will to take this person whom you see here before you as your spouse. Again, there is a Eucharistic parallel to this mystery: man cannot become the Body of Christ; God cannot turn man into the Body of Christ against man’s will; only at the intersection of God’s will and man’s will the sacrament of the Body happens.

On the other hand, I also have to pause and ask what exactly the two people are consenting to or willing to do? It is certainly not the matter of living together or having babies–people have been doing that without the Church’s blessing for thousands of years. So, when we speak of marriage as an icon of Christ and His Church, it is not the image of cohabitation or procreation but of martyrdom. The crowning, the central element of the service, really only has one meaning–the bestowal of the martyr’s crowns. The real question to which the spouses respond, “I do,” is not whether they want to live together and make babies, but whether they are accepting the cross and making the sacrifice: “Do you have the free and unconstrained will to give your life for this person whom you see here before you? No lists of vows or contracts with small print to negotiate, because when you give away your life, you give it all and you lose it all, expecting no barter, or deal, or benefit in return.”

I think that this is the only way that the question about the free will makes sense. Marriage may be pre-arranged or the decision is constrained in some way–and this is acceptable, but the self-sacrifice in the image of Christ is a free choice, just like His.

How is this concept expressed liturgically? I think that the connection between wedding rites and the Eucharist is not a mistake–it makes intuitive sense, even if it lacks historicity. Thus, ideally, every Liturgy should point to Christ’s sacrifice to us and compel us to reflect this image back to our spouses and to the world. And when Christ’s self-sacrifice is realized as the model for our marriages, the Eucharist becomes the liturgical expression of answering “I do,” which then transforms that brief moment at the beginning of the wedding service from something temporal and not altogether memorable into something which is connected to the timelessness of the Eucharist.