A translation of American journalist William Lobdell’s book, Losing My Religion: How I Lost My Faith Reporting on Religion in America – and Found Unexpected Peace, has recently been published in Russian. This book is interesting in many regards. Lobdell cannot be placed alongside the popular anti-religious propagandists; he is a much more serious and profound writer. Most likely this comes from his experience as a professional journalist. Lobdell raises a series of very important questions that we would do well to consider. One of these questions concerns bad religious people, which the journalist sees as the main reason for his fall from faith.

Lobdell writes about egregious cases of pedophilic Catholic priests and how the fact that these cases took place decades ago, with the victims now long part forty, renders them no less egregious. He writes about how the ecclesiastical authorities maintained a policy of “not airing dirty laundry in public,” allowing the villains to inflict more harm than if they had been properly dealt with at once. He writes about Protestant televangelists who preach the “Prosperity Gospel”: donate all your money to them as an act of faith and firm hope in God and He will “bless” you with healing from all illnesses and with heaps of money. Many people give their last resources or, as an “act of faith,” even refuse essential medical procedures in expectation of the promised “blessing” – alas, in vain. Meanwhile, these televangelists live on these people’s money in luxury and debauchery, from time to time getting involved in public scandals.

Lobdell writes about egregious cases of pedophilic Catholic priests and how the fact that these cases took place decades ago, with the victims now long part forty, renders them no less egregious. He writes about how the ecclesiastical authorities maintained a policy of “not airing dirty laundry in public,” allowing the villains to inflict more harm than if they had been properly dealt with at once. He writes about Protestant televangelists who preach the “Prosperity Gospel”: donate all your money to them as an act of faith and firm hope in God and He will “bless” you with healing from all illnesses and with heaps of money. Many people give their last resources or, as an “act of faith,” even refuse essential medical procedures in expectation of the promised “blessing” – alas, in vain. Meanwhile, these televangelists live on these people’s money in luxury and debauchery, from time to time getting involved in public scandals.

Indeed, “bad religious people” is the most popular argument against the Church and against faith in God generally; we would do well to consider it in detail. Lobdell bases himself on Western material, but we should not take comfort in this: there are nasty religious people everywhere.

Of course, much that is simply bunk gets published in the scandal sheets. But there are also real evildoers. Why am I so certain of this? Because it says so in the Gospel: Many will say to Me in that day, Lord, Lord, have we not prophesied in Thy name? and in Thy name have cast out devils? and in Thy name done many wonderful works? And then will I profess unto them, I never knew you: depart from Me, ye that work iniquity (Matthew 7:22-23). The people being spoken of were Christians in both name and appearance – moreover, they were quite active and prominent Christians. They prophesied in the name of Christ, cast out demons, and even worked miracles – but the Lord says that they were strangers to Him all the while. He never knew them.

How should we react to such people? Lobdell describes two reactions: he himself walked away from faith in Christ. But he is honest enough to point out examples of another choice: people, themselves believers, who take great pains to expose false preachers out of their devotion to the Lord. Many people who have suffered from religious scoundrels have kept their faith. They are no less outraged by iniquity than Lobdell; unlike him, many of them have suffered personally. But they have remained with Christ. Why? Because this was their personal choice. In this situation, who chose wrongly? Let us try to get to the bottom of this.

The reality of the choice

We ourselves decide whether or not to believe in Christ. To say, as Lobdell does, that “people who identified themselves as Christians had driven me away from a faith I loved” is to engage in self-delusion. One might say: “I made the decision to leave the faith (or to refuse to believe) for such-and-such reasons,” and then examine the reasons behind this action. One person might consider them valid, another not. But the notion that someone else makes our decisions for us should be put aside in any serious conversation. If you have made the right decision, then why ascribe it to others? If you are just a feather in the wind, and if your decisions are made by some external power rather than by you, then discussion is pointless. Discussion of the reasons for our decisions, and in particular how bad religious people have influenced them, can come about only if we make our own decisions.

Guilt by association with scoundrels

Once I happened to say some good things on my blog about our Uzbek concierge. One commentator bitterly reproached me for praising an Uzbek on the anniversary of a high-profile crime committed by other Uzbeks. These were indeed monstrous and shocking crimes; it was obviously expected of me to redirect the indignation caused by these atrocities by association to another person, our innocent concierge. I was being reproached for not redirecting this indignation.

Guilt by association with scoundrels is fairly simple. First, elicit righteous indignation; second, readdress it by association to someone else. There is nothing specifically anti-religious in this; it is anti-whatever. It can be used against any randomly selected group of people: Uzbeks, the police, coaches, Jews, teachers, doctors, Russians, Americans, or cyclists. (Did you know that during the First World War Hitler was a courier and went about on a bicycle? Those awful cyclists!)

The weakness of this approach is that it is openly manipulative: no attempt is made to convince you by argument that the concierge is an evildoer; they incline you to hate her using a wave of emotion stemming from crimes committed by someone else entirely.

Its other weakness is what might seem its strength: its universality. Among any group of people – doctors, teachers, scientists, whoever – one can find plenty of scoundrels within minutes. Doctors have experimented on prisoners, teachers have beaten students with rulers, and scientists were largely responsible for Hiroshima. Do you hate physicists as much as I do? No? Then you are a very, very bad person who does not care about the horrible death of children in Hiroshima!

In order to become a victim of manipulation – whether nationalist, anti-scientific, anti-religious, or whatever – there is a certain element of acquiescence and consent: “I’m glad to delude myself.” We need to decide whether we are in fact glad to delude ourselves. Someone who has kindled a sense of righteous indignation within himself on account of some truly evil deed and who then readdresses it to other people can easily feel himself to be in the right. The question is whether we want to feel ourselves to be in the right or whether we want to be right. One can turn to guilt by association with scoundrels in order to suppress one’s own doubt, or one can carefully examine these doubts to see just how well justified they are. This is what we will do now.

The grounds for choice

Lobdell, to his credit, also mentions some good and honest believers, whom he even admires. He mentions that the majority of Catholic priests did not commit any crimes and that there are televangelists, such as Billy Graham, who are entirely blameless – except for the fact that their faith in God (from Lobdell’s perspective) is mistaken. He speaks warmly of the pastor of the community to which he belonged until he decisively left the faith. Then why did he make his decision based on bad people? Are these people in the majority? No – and he makes no attempt to pretend that they are. He admits that his experience was formed by the fact that he, as a journalist, investigated instances of abuse – just as officers investigate murders. An ordinary citizen (and not an investigating officer) might never in his life meet a murderer; the ordinary member of a religious community will never see the awful religious people about whom Lobdell writes. Do their communities offer them as role models? Do they approve of their behavior? No, certainly not. Then on what grounds must they be used for deciding on faith in God? Why, on a bunch of grapes, is it necessary to search out the rotten ones?

I am afraid that I understand why. Scoundrels and their scoundrelism make us feel bad about the world in which we live and in which they do such terrible things. But they help us to feel good about ourselves: compared to them we have reason to see ourselves as good and virtuous people full of righteous indignation, as indignant prosecutors – and by no means as the accused. Ordinary people do not make us feel so good about ourselves. With genuinely good people things become even worse: we understand that compared to them we look quite trifling. We feel as if we are being judged: why did we not become like them? What is preventing us? Nothing. We simply have not wanted to. It is not sinners, but the righteous who make us feel uncomfortable.

How can we respond to this discomfort? Here we find ourselves at a crossroads; we need to decide what we want. We might want to improve ourselves, to change, to set out on the path of moral growth – in which case we will look for good examples. We will seek out fellowship with virtuous people and read about such people whom we can no longer meet (on earth, at least). We will become interested in good people in order to emulate them. But we can also choose another path: to suppress every feeling within ourselves that there something is wrong with us and that we need to change. Then we will be in urgent need of the scoundrels, whom we will search out. They can be found; they do exist. But the question remains whether we want to make vital decisions by basing ourselves on scoundrels.

“Be ye not unwise”

Let us return to the words of the Gospel we cited at the beginning of this article: the Lord never knew some of the people who played the role of spiritual leaders. The New Testament is full of warnings against false prophets. The spiritual journey can be dangerous. There is nothing specifically religious about this: living among people endowed with free will is always difficult. Sometimes people are faced with betrayals that leave deep wounds that take a long time to heal. A young woman, madly in love, might marry a brilliant, artistic, charming young man – who can then turn out to be a psychopath who will turn her life into a living hell. Someone can trust his best friend, who might then betray him. Trust always involves risk. Wherever relationships are built in trust, whether in the family or in the Church, there is always the danger that someone will misuse it. Moreover, sometimes very bad people have the ability to produce an initially very positive impression.

This is no reason not to marry, not to become friends with anyone, or not to join the Church. By avoiding people you might insulate yourself from betrayal, but even more surely you will insulate yourself from love and friendship and, ultimately, from eternal salvation. But this is reason to be prudent: that scoundrels manipulate people’s best (especially religious) feelings is, alas, a reality.

Those who attack our faith often call it “credulousness.” There is nothing further from the truth: the Prophets, the Apostles, and the Lord Jesus Himself repeatedly call us to prudence and discernment. Faith is devotion to God’s truth, the readiness to endeavor to find it and to amend one’s life in accordance therewith. Faith may require you to confront evildoers and deceivers in the name of Christ, Whom they betray, and in the name of the people they harm.

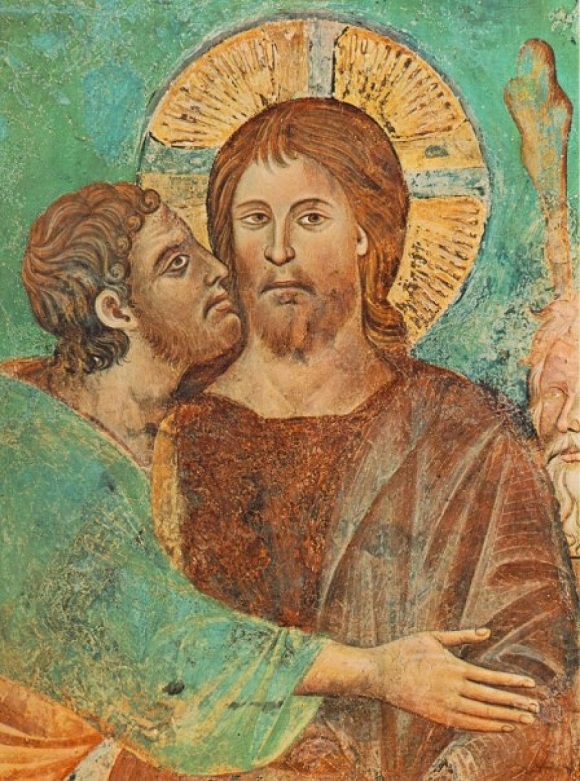

Yes, there have been traitors in Christ’s army, beginning with Judas Iscariot. But if you decide to desert, making reference to these traitors, then this is your decision and not theirs. Someone else’s treachery cannot prevent you from remaining loyal – if this is in fact what you want to do.