And be not conformed to this world; but be ye transformed by the renewing of your mind, that ye may prove what is that good, and acceptable, and perfect will of God. (Rom. 12:2)

Some time age I accepted a parish that had many third- and fourth-generation émigrés: Just as had their fathers and grandfathers, these parishioners devoted a good deal of energy and money to the growth of their church, building an impressive modern-style edifice in a prosperous section of their city. They organized many social and profit-making events, kept their finances with a bookkeeping system that could have matched that of any reputable business, and in general seemed a model enterprise. Having spent all my years as a priest in relatively poor and small communities, I expected to welcome the material change.

Some time age I accepted a parish that had many third- and fourth-generation émigrés: Just as had their fathers and grandfathers, these parishioners devoted a good deal of energy and money to the growth of their church, building an impressive modern-style edifice in a prosperous section of their city. They organized many social and profit-making events, kept their finances with a bookkeeping system that could have matched that of any reputable business, and in general seemed a model enterprise. Having spent all my years as a priest in relatively poor and small communities, I expected to welcome the material change.

Very soon, however, the contradictions between form and content began to appear. No one came to vespers and matins services on Saturday nights, children were taken away for religious lessons from the Sunday Liturgy itself, and the bulletin’s persistent “did you light a candle for, someone today?” began to sound more like a .demand for money rather than a suggestion to remember the faithful in one’s prayers. Our whole family began to feel part of an actor s troupe, coming out for performances at the scheduled times. The secular world of drama, however, can prove surprisingly moving on occasion, but religion here did not appear to offer even this satisfaction. Growing increasingly dismayed at the dearth of genuine spiritual life, I began to search for an answer.

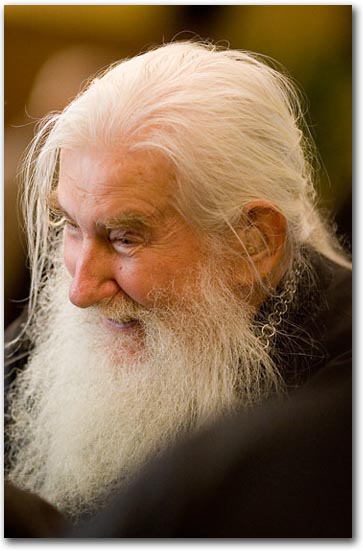

I did not have to look long. The members of the General Committee approached me themselves with what they, too, perceived as a problem. Just as I worried over their overlooking the forms of Orthodoxy–attending services, privately praying, keeping the fasts–so they felt concern over my preserving the forms. They wanted someone who could continue to lead the parish along the course it had developed for itself in isolation over the decades: integrating with modern society around it to satisfaction, it was a community of already well-established and upwardly mobile businessmen, both full of ambition and the desire to succeed, wanting a pastor and parish commensurate with the status they desired. And so they approached me, a man admittedly poorly versed in the’ ways of the corporate world, with a specific request. Could I cut my hair and beard, wear a dark suit and collar instead of black robes? My appearance as an Orthodox priest struck too much of a jarring note; it did not fit in with their image of a proper leader. The classic ideal of an Orthodox pastor walking within those living on the earth as a reminder of the other world only disconcerted them as an awkward anachronism. I went home that night to think about my obligations both as their parish priest and as a servant of the Orthodox Faith, about form and essence, and realized several things.

Why am I the way I am, I wondered. It is not because I am stubborn. It is possible that the modern way would even be more convenient for me. But I am Orthodox. It was my personal decision during World War II to serve God as an Orthodox priest, and appearance is an integral part of this.

If we study Church history and the lives of our martyrs, we find that they often gave up their lives for Orthodoxy, even though sometimes nothing special was asked of them–only some incense · in front of an idol, for example. They could have done that and remained orthodox at heart, going on to many good deeds. For some reason, however, they preferred to give up their lives so that generations to come would have an example of how to cherish this Orthodox Faith. Our faith is interwoven with traditions and customs, like a beautiful design. When one takes something out, it loses its completeness. And yet, if we look back over time, we will notice that instead of preserving Orthodoxy, we keep adjusting it to the times.

In the time of St. John Chrysostom, the saint was concerned that people came to church, but did not take part in Holy Communion. Through the centuries, however, people grew used to this, and now they consider it odd if someone goes to Holy Communion· very often. As the years went by, people started breaking the fast on Wednesdays and Fridays and other prescribed fasts. Later it became too much for them to attend services in the evening, so in many parishes they are omitted entirely. Later some decided that it was too hard to stand through the one service they did attend, so they have the pews. Sometimes people are ashamed to cross themselves in public, so they avoid it. In some parishes they have even changed the calendar, and who knows what other changes the times will demand. Future generations coming into a modern Orthodox church will well wonder what the difference is between the Orthodox Church and the Western churches, and why bother going to the Orthodox Church if it is like the one next door.

We must be very careful. Do we want to be Orthodox in name only, or Orthodox in faith? Calling oneself Eastern Orthodox and feeling Orthodox within cannot be separated from being Orthodox in our actions as well. Our faith is many things, but it is above all a light illuminating all aspects of our life. It is both a miracle and the most natural thing in the world . The earth’s ephemera will always flit past to catch our fancy, but it can only underscore the eternity of our faith. We can love the life Christ redeemed through His Resurrection, and we can love the life to come still more.· As long as we are soul and body, creatures of both matter and spirit, we need-to fulfill Orthodoxy’s instructions on both. Let us rejoice in our unity within the Eastern Church, try to unite form and spirit, and “commit ourselves and one another and all our lives unto Christ, our God.” Amen.

Orthodox America, Issue 19, Vol II, No. 9. May, 1982