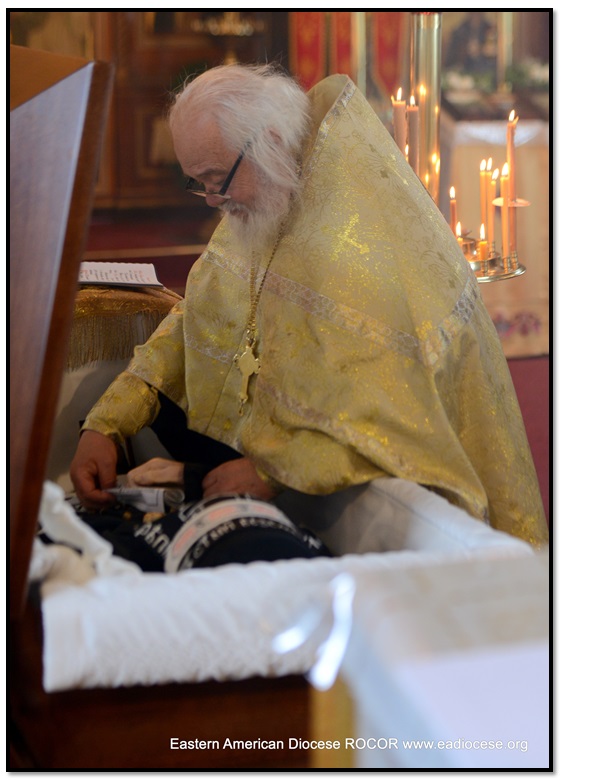

On Friday, January 10, the funeral for Abbess Irene (Alexeev) was held at Holy Dormition Convent “Novo-Diveevo” in Nanuet, NY. Abbess Irene was rectress of the convent, and reposed on Wednesday, January 8, the feast of the Synaxis of the Mother of God. With the blessing of the First Hierarch of the Russian Church Abroad, the funeral was led by His Eminence Gabriel, Archbishop of Montreal & Canada.

His Eminence was co-served by monastery cleric Archpriest Alexander Fedorowski, New England dean Archpriest George Larin, diocesan secretary Archpriest Serge Lukianov, Archpriest George Kallaur (rector of the Church of our Lady “Unexpected Joy” on Staten Island, NY), Archpriest Ilya Gorsky (cleric of Holy Virgin Protection Church in Nyack, NY), Archpriest Mark Burachek (rector of Our Lady of Kazan Church in Newark, NJ), Archpriest George Zelenin (rector of St. Michael’s Cathedral in Paterson, NJ), and Priest Vladimir Kaydanov (cleric of St. George’s Church in Howell, NJ). Praying in church were the recently orphaned sisters of Novo-Diveevo Convent, as well as many pilgrims, who came to pay their last respects to the Mother Abbess. The choir sang prayerfully under the direction of monastery cleric Protodeacon Serge Arlievsky.

Upon conclusion of the funeral, Archpriest George Zelenin addressed the faithful with the following sermon:

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit! We have been orphaned today; our convent has been orphaned. The sisters of this convent have been orphaned first and foremost. But orphaned also are all of us who, while the Mother Abbess was still alive, could come to her and receive more than anyone can receive from someone steeped in wisdom and experience: we could receive not only counsel, but also that which holds the entire world in place, which is stronger than any life experiences: we could receive prayerful support, without which it is impossible to survive in this life, and which is truly greater than any merely human experience. Moreover, we have been orphaned because now we feel as never before that, in the spiritual war being waged in this world, we no longer have this reliable, very firm line of defense against the enemy of mankind. There has been a breach in the front. And it would be good if we could close this breach. But if not? What if we cannot attain this same experience of prayer, this experience of the spiritual life, which is at all times eternal, which unites all times, and of which the Mother Abbess was the standard? She was born with the name Zoya in a simple Cossack family in 1922, in a small Cossack military village on the banks of the Amur.

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit! We have been orphaned today; our convent has been orphaned. The sisters of this convent have been orphaned first and foremost. But orphaned also are all of us who, while the Mother Abbess was still alive, could come to her and receive more than anyone can receive from someone steeped in wisdom and experience: we could receive not only counsel, but also that which holds the entire world in place, which is stronger than any life experiences: we could receive prayerful support, without which it is impossible to survive in this life, and which is truly greater than any merely human experience. Moreover, we have been orphaned because now we feel as never before that, in the spiritual war being waged in this world, we no longer have this reliable, very firm line of defense against the enemy of mankind. There has been a breach in the front. And it would be good if we could close this breach. But if not? What if we cannot attain this same experience of prayer, this experience of the spiritual life, which is at all times eternal, which unites all times, and of which the Mother Abbess was the standard? She was born with the name Zoya in a simple Cossack family in 1922, in a small Cossack military village on the banks of the Amur.

She was, from her birth, a true picture of humility. She always maintained that her very life on this earth was a miracle. It so happened that she was the fourth child born in her family ‒ three children died in infancy, and she herself was born very weak. But the Lord appointed for her a different path: she survived, and became very strong. And her life was one of great hardship. We know and remember what was taking place in 1922 in our homeland, especially in Siberia, especially in the Amur region (Outer Manchuria), especially in those places. Her family was not exempt from deep sorrows and tragedy. More than once she would share the recollections of her father – an Amur Cossack, a warrior, a hero, a paramedic – a healer of human bodies and of their souls, as well, because he was able to raise her in the same spirit. She would recall how they fled after the persecution of dekulakization, first to the neighboring village of Nikolskaya where her grandmother lived, and later farther, in 1928, to Harbin, China. Here began her travels and years of exile. She attended school there, and it was there, after the death of her sister in 1946, that she came as a 24-year-old girl to the monastery. The Mother-Abbess herself – and herein also lies a great act of her humility – would share stories of her own blunders in life. But these blunders revealed something entirely different – they revealed the greatness of this person’s spirit. “The first day, when I came to the convent – it was one of the more famous monasteries, of the four in Harbin (two male, two female), named in honor of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God ‒ I entered the territory of the convent and did not know to whom to turn. I looked and saw a nun lighting a samovar. I approached her and asked where I should go. She did not respond. I stood there in silence. Much time went by, until someone appeared and explained where I should go. Only much later would I come to find out that the nun in question was deaf and dumb.” But she, in her humility, stood there, patiently waiting for someone to take notice, waiting for someone to answer her question.

This was her greatest trait – her humility, which conquered all in her life, and became her lifelong companion. Even there, in the convent, all did not go swimmingly. We do not now know the reasons, but for whatever reason the abbess at that time was forced to leave the convent and live in the city. And she became her cell attendant. In obedience she went, humbly, with the abbess and cared for her all those years, until the Lord called away her spiritual instructress – Mother Irene. For this reason there was great joy when then-Fr. Adrian (the future Archbishop Andrei) tonsured her with the name Irene. How great was her joy! She would speak of this often later in life.

She arrived here in the convent in 1962. She was one of the last nuns to come from Harbin. Let us recall that this was in the years of the Cultural Revolution, years of terrible persecution, which every Russian in China endured. She did not leave, because she was caring for the elderly abbess, and would not evacuate from China until she had fulfilled her obedience. Moreover, she was supposed to wind up with her sisters at the Convent of our Lady of Vladimir in California. But it seems that she was so weakened by the journey, or perhaps there was another reason, that she was told to stay here. They feared that she would not survive all the way to California. And the nuns here recalled – this may be hard to imagine – that she arrived a tall, very tall, young woman. It is hard for us now to see a tall, stately Cossack woman in the hunched eldress that we knew. No one knows how much she weighed then, but she arrived at the convent’s threshold a skeleton, skin pulled tight over her bones, her clothes hanging off of her, as though on a hanger. The older nuns hustled and bustled to restore her to health, feeding her ice cream. And they did not labor in vain: they received first a wonderful sister, and later a mother for their entire habitation.

Here is one curious instance relating to her arrival at the convent. She did not know how monastery life worked here, and knew nothing of Fr. Adrian. “The first, then second days passed, then a third, and suddenly the nuns approached me, saying: What’s the matter with you, little dove, that you won’t go up to Father? He’s getting annoyed. But I didn’t know who he was, I didn’t know anything.” How much humility and simplicity! Of course, Fr. Adrian warmed up to her, and soon grew to love the future abbess, the future Mother Irene. It is no coincidence that the future abbess bore the obedience of serving on the kliros, among her other obediences. That was a characteristic trait of hers, that she would fulfill without complaint the most varied obediences; but her primary job was on kliros. How and where did she learn to sing on kliros, how and where did she acquaint herself with the order of church services? We only know that she did this in the years she spent in Harbin, while living with the abbess, for whom she was caring; while she was with her family, attending church; and, principally, here in the convent, where her every day, as an assistant to the future Archbishop Andrei, was filled with the countless panihidas that were served here. According to some, on Sundays they would return from the cemetery only at four o’clock in the afternoon, when Liturgy had finished at 11 that morning. The whole day was full of labors of prayer. So she continued under Fr. Alexander, and Fr. Alexander can testify that for more than ten years she bore this obedience, until a new obedience was placed on her.

And throughout all this, one of the most striking characteristics of the Mother Abbess – and we already heard of her humility and obedience – was her vow of constancy, which every monastic vows, and which she fulfilled in her life. Few know this, but in her more than 50 years in the monastery, the Mother Abbess left its walls once in her life. And even then it was not of her own accord. When the elder sisters, participating in a charitable lottery, won a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, they forced their younger sister to travel. This was the only time in 50 years that she left the convent grounds! Of course, this does not include the final years, when she had to go the hospital, but again this took place only in obedience. She did not want to leave the convent. But if those two magic words were spoken – “Father said, so I must go,” that was the end of it, with no argument, no debate. What a stunning example of obedience.

Even her entire life here, in the convent, the minutes and hours when she was free from any monastic obedience were spent in her small, salvific triangle ‒ the church, her cell, and the refectory. Even here no one saw her wandering about without purpose. And of course the cell is a continuation of the church; the refectory is a continuation of the church; it is ceaseless, unbroken prayer. This is why I say that she could give us more than anyone who is wise with life experience: she learned to pray in life, and prays for us now. Can we close this breach; can we learn to pray as she prayed?

Now we have a good chance to accomplish this for ourselves. Moreover, we now have a faithful intercessor. She now stands before the throne of Him, to Whom she was betrothed in life. Awaiting her now is a meeting with her Bridegroom, and there, with her Bridegroom, she will continue to pray, and pray for all of us. And we here will pray for her. Amen.

The burial of Mother Irene was held in the monastic section of the Novo-Diveevo Cemetery. Memory eternal to Abbess Irene!

Source: Eastern American Diocese ROCOR