Myth:

Christianity, which recognizes only one God, engenders intolerance, conflicts and fanaticism, while paganism, easily recognizing many gods, leads to tolerance and peace.

As Schopenhauer said, “As a matter of fact, intolerance is only essential to monotheism: an only god is by his nature a jealous god, who cannot permit any other god to exist. On the other hand, polytheistic gods are by their nature tolerant: they live and let live; they willingly tolerate their colleagues as being gods of the same religion, and this tolerance is afterwards extended to alien gods, who are, accordingly, hospitably received, and later on sometimes attain even the same rights and privileges.”

And in fact?

We believe in the One God, and this means that all people, our friends and enemies, near and far, were created by Him. As one person said, “you cannot love an artist and hate his paintings”. Moreover, God considered His creations so valuable that He became a man embodied in Jesus Christ and accepted suffering and death for their salvation.

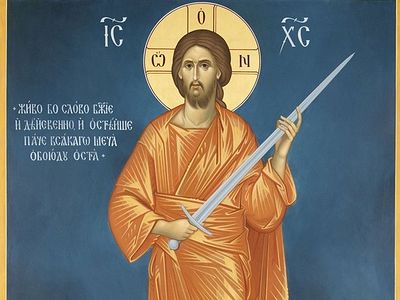

Any person, regardless of his race, nation or religion, was created by God in His image; Christ died for this person, as for all of us. Our faith, which teaches us to reject false gods, also teaches us that their worshipers, even though they are in delusion, are precious in the eyes of the true God, Who will have all men to be saved, and to come unto the knowledge of the truth (1 Tim. 2:4).

Intolerance – the inability to coexist in peace with your neighbors, which differ from you in something: a shade of skin, language, religion, views or customs – is an undoubted sin. As the Scripture says, depart from evil, and do good; seak peace and pursue it (Psalm 34:14).

But something else can also be called intolerance: the setting of clear boundaries and limits, doctrinal and moral, which separate true faith from error.

You may be accused of intolerance if you refuse to recognize a foreign religion as true as your own, or if you do not want to recognize a heretic as a member of the Church.

Religion scholars, however, call this attitude not intolerance, but theological exclusivism: a belief in the exceptional truth and salvation of their religion.

Does Christianity imply such exclusivity?

Yes, it does. The Bible excludes worship of other gods. As stated in the first commandment of the Decalogue, I am the LORD thy God, which have brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. Thou shalt have no other gods before Me (Exodus 20:2).

Moreover, there is a dogma in Christianity: a set of obligatory creed statements about God, so a person who refuses to share them cannot belong to the Church. Just as a person who openly rejects the commandments of God cannot belong to the Church (in our days the commandment “thou shalt not commit adultery” is in the worst position).

This stands in contrast, which is unpleasant for many people, with the practice of paganism, which is much more open both in dogma and ethics.

Pagans are usually ready to accept other gods with open arms and include them in their pantheon. This attitude is called religious pluralism. For Christians, it is incogitable.

Many see this as the root of intolerance in the history of the Christian world: the persecution of heretics and so on. But is it really so? Is there an easy way to test if there are intolerance and persecution in the pagan world? Indeed, if Christianity is the source of this evil, then in cultures that are not affected by it, things should be much better.

For example, Hinduism (and India is the last great ocean of paganism) is so undoctrinaire that religious scholars argue about whether it can be considered a single religious tradition, or it is more appropriate to talk about “Hinduism” as different religious systems, united only by belonging to a common cultural world of the Indian subcontinent.

Within the framework of Hinduism, there is a huge variety of deities, philosophical schools, spiritual practices, ideas about the universe, myths and narratives flowing into each other.

Although there is a practice in Hinduism called bhakti which means personal devotion to a particular deity, none of the Hindu gods require “Thou shalt have no other gods before me.” On the contrary, even within the framework of Krishnaism relatively close to monotheism, it is believed that by worshiping other deities, a person ultimately worships Krishna.

How are things going with the pagans? Does religious pluralism lead people to get along better with each other?

The historical experience of India shows that this is not true: the subcontinent has not only no less bloody history than Europe, but is still shaken by sharp intercommunal clashes, in which Hindus play a significant role. Indian cults can be of a very gloomy nature, such as, for example, a sect of the Tugs who worshiped the goddess Kali. According to historians, there are about a million murders devoted to her under their belt.

Turning to another great pagan culture, Buddhism, we find a no less turbulent history and not too blissful modernity. For example, in Burma, the militants persecuting the Rohingya Muslims are led by the Buddhist monk Ashin Viratu.

In practice, pagan cultures do not at all seem more tolerant.

What is the main mistake behind this myth? There are two views on the nature of evil. According to one of them (in the European tradition, it is primarily associated with the name of the French sophist of the XVIII century, Jean-Jacques Rousseau), a person is born good, and some external factors – the wrong social structure, religion, lack of education, repressive morality – spoil him. If you get rid of these factors: reorganize society on the basis of reason, save people from religion (or, at least, from the “wrong” religion), conduct the right training, then you can build a wonderful utopia. Experience shows that this does not work, or rather, makes the situation only worse.

According to another view, evil is a manifestation of the Fall. A man rebelled against his Creator and deeply damaged his nature, so the heart [of men] is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked (Jer 17:9), and, as Christ says, from within, out of the heart of men, proceed evil thoughts, adulteries, fornications, murders, thefts, covetousness, wickedness, deceit, lasciviousness, an evil eye, blasphemy, pride, foolishness: all these evil things come from within, and defile the man (Mark 7:21-23).

Evil is not imposed on man from the outside, it emanates from within and distorts everything: religion, social life, and it is sin, rooted in the human heart, that is the source of intolerance.

Who benefits from this myth?

First of all, those who, for one reason or another, would like to completely get away from the question of the truth of Christianity. Instead of discussing the substance of the question, “Is the Gospel true?”, they divert the discussion to the side of its supposed intolerance.

But any truth can incur reproaches of intolerance. Doctors are hostile to charlatans and all kinds of occult “healers”. Historians flatly refuse to recognize academician Fomenko and other authors of popular pseudo-historical works as their followers. Physicists look at the “theory of torsion fields” and other pseudo-scientific constructions extremely coldly. Why? Is it because science, and especially medicine, makes people intolerant of evil? Obviously, it is not. They simply proceed from the fact that truth exists and matters. True love for people requires that we adhere to this truth: medical, scientific, historical, and certainly theological.

Translated by Alyona Malafeeva