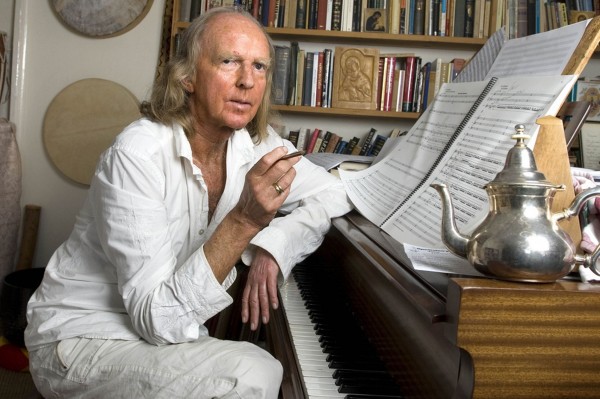

At the conclusion of the festival, Pravmir interviewed the British composer and conductor, Archpriest Ivan Moody of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, who had personally known and worked with John Tavener.

Father Ivan, will you please tell us about the festival “From Taverner to Tavener. Five centuries of English sacred music.” which was held in Moscow? How did the Russian audience like the music by Sir John Tavener?

The festival was intended to make both English renaissance sacred music (Taverner) and English contemporary sacred music (Tavener) better to known to Russian audiences. A great deal of interest was generated both by the concerts and the musicological conference.

You are a priest of the Orthodox Church, pastor of the church of Saint John the Russian in Portugal, could you tell us, please, how did it come about that you found yourself in the Orthodox Church, what has influenced your choice?

It came about as the result of a good deal of searching, for the fullest expression of Christianity. The idea that the theology of the Church is made manifest in its worship led me from the beauty of the Byzantine rite to the beauty – and the truth – of its theology. When I became Orthodox, at about the age of 23, I sang in the choir of the Russian Cathedral in London, under the direction of Father Michael Fortounatto. We would sing the service of the Resurrection at Pascha knowing it was being transmitted to Russia. At that time Metropolitan Anthony (Bloom) of Sourozh was still very active, and a great inspiration.

You are also known as a composer, choir conductor, chairperson of the International Society of the Orthodox Sacred Music, what do you think is the influence that sacred music has on the contemporary classical music? Is there, in your opinion, the interpenetration between the sacred music and the classical music?

I think there can be, yes. I think that there is, so to speak a “space” between the Church and the concert hall, where paraliturgical music has a place. I do not consider myself a “church composer”, and do not train my students to become Kapellmeisters; I think that in order to write good church music one must have the full technical range and abilities available to any composer. But to answer your question more directly, when I write music for the concert hall based on sacred texts, for example, I am writing for this “space”, but never with the intention of converting people. The music is what it is, and must stand or fall as music. Many of my works fall into this category, such as Anastasis, based on texts for Holy Week and Pascha, and Seven Hymns for St Sava, using vesperal texts in honour of the Serbian St Sava. There is also the problem of what is often called “spiritual” music, a label often used for music that is simply slow and relatively free of dramatic incident – New Age, if you like. This is not “spiritual music”, but a kind of whitewash. Real spiritual music, from the Orthodox perspective, must be incarnate, not insubstantial. How else can it project the Resurrection?

Orthodox choral singing is in the first place singing of the choir at the divine service, how can the tradition of Orthodox choral singing be popularized in the modern society?

Firstly I have to say that there is a great deal of interest in Orthodox church music as an aesthetic phenomenon, which can also lead to a deeper appreciation. I see this a great deal at the various conferences and festivals I attend, including those of the International Society for Orthodox Church Music (www.isocm.com). Very often people are struck immediately by the beauty of the singing when they attend an Orthodox church for the first time, and it is important to remember that music is one of the ways by which God can call us. Equally, I believe that we need to involve contemporary composers in composing for the Church, but for this to happen there needs to be an awareness of the Church’s musical traditions.

You work with the choirs in Europe and the USA, what kind of music do you sing? Will you please tell us about your methods of work as a choir conductor?

I tend to concentrate on contemporary church (and paraliturgical) music, not only my own, but, for example, the work of contemporary Finnish, Serbian or Greek-American composers, but I have also tried to promote more generally the music of Bulgaria and Serbia, little-known outside these countries, in a number of concerts. I have just been conducting on a course in Serbia, and we sang music by the Greek-American Tikey Zes, by John Tavener and by me. Next year in the USA I will conduct the Penitential Psalms by Alfred Schnittke, and music by Galina Grigorjeva and by me. Conducting methods vary according to what kind of choir I am dealing with: in the case of Cappella Romana, with whom I often work as a guest conductor, we are talking about a very high musical level and one can concentrate on the tiniest details of the music. In other cases, where I may be dealing with a choir of young students on a choral course, the approach has to be different and more directed to practical things such as singing through lines, projecting text and even simply learning the notes! But in all cases it is important to transmit an understanding of the music you are performing, and know its context, liturgical and spiritual.

What Russian or Western composers of sacred or classical music do you feel closest to as a composer? What musical traditions paved your way as a composer?

I love many traditions of Orthodox chant, both monophonic and polyphonic. I greatly admire the work of conductor Anatoly Grindenko, for example, in Znamenny and other Russian chant repertories; I also have a great love of Byzantine and Serbian chant traditions, and have worked with all of these in my own music. As for contemporary composers who interest me, I could mention Alfred Schnittke, Sofia Gubaidulina, Valentin Silvestrov, Giya Kancheli, Arvo Pärt, Henrik Mikolaj Górecki, Peter Sculthorpe, James MacMillan, John Adams, Einojuhani Rautavaara and, of course, John Tavener. I also feel very close to English music of the renaissance period – Taverner, Sheppard, Tallis, Byrd. And from the 19th century-20th century, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov, Puccini, Elgar, Britten, Shostakovich…

Have you ever met John Tavener?

Yes indeed! I studied with him for several years, and he was the godfather at my wedding. I knew him very well.

Have you ever cooperated with him as a composer? What do you like in John Tavener’s music?

I have conducted many of his works, and organized concerts with him in London when I had a chamber choir there: we gave the London premières of several of his works, and the first performances of such works as the Panikhida and Apolytikion for St Nicholas. What I admired in Tavener’s music, and what led me to study with him, was the great transparency in works such as the Great Canon of St Andrew of Crete or Ikon of Light, and at the time he was the only composer working in England to be so openly concerned with the question of the sacred in music. But I also already admired his early work, the richness of such pieces as Celtic Requiem and the austerity of Requiem for Father Malachy and Canciones Españolas, for example. I was present at the première of the Vigil Service in Oxford in 1984, and that made a huge impression on me, with its “pan-Orthodox” tapestry, as the composer said, from Byzantium to Russia. One thing I particularly remember is him showing me the newly-completed score of The Protecting Veil: he was concerned that he had written something unacceptably romantic!

In 1977, John Tavener was baptized by a famous Metropolitan, Anthony of Sourozh, and later he said: “The fact that I accepted Orthodoxy is highly significant and so is the fact that my music is inspired by Orthodoxy”. Was John Tavener always true to these words in his music?

This is a complicated question. Initially, yes. He would talk of nothing but the decadence of the West and its music, the Byzantine octoechos, and so on, and all his music looked to Orthodox sources, whether Russian or Greek. But his spiritual orientation changed later in life – he felt that he could draw upon other religions for his sources, in a search for the eternal wisdom, the Sophia perennis, but he insisted that he remained Orthodox in his personal spiritual life. I found this difficult, and we had long discussions about it, but that was his position.

John Tavener said that Orthodoxy helps him to “move the hearts of the English people”. Do you think that there is an evident influence of John Tavener on British Culture by means of Russian spirituality?

I think that many people responded to his music in a way that nobody would have predicted, to its transparent openness to the sacred. But people were free to interpret that music as they wished: I cannot say that particularly Russian (or Greek) spirituality had a large impact, but the fact that he was concerned with these things certainly did. Two very good examples are The Protecting Veil, which is based on the theme of the Protecting Veil of the Mother of God (Покров). Many people wrote to him after its first performance because they were dazzled by it, moved by it, touched by it, but one cannot say that all those people responded directly to its Orthodox “programme”. The second is Song for Athene, which mixes Orthodox funeral texts with excerpt from Shakespeare, and which was sung at the funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales. That piece achieved a similar thing, but it was intimately involved with the unique nature of that occasion, and suited it perfectly. I think, actually, that this is one way in which Orthodoxy can reach out to people of different faiths, or of no faith.

Orthodox choral singing is based on a capella singing, without the use of musical instruments. John Tavener has followed this tradition. Why is the voice the best musical instrument? Do you use a capella singing in your compositions?

Yes, of course, both when writing specifically liturgical music and music for the concert hall. In fact, one of my longest works, the Akathistos Hymn (Акафист) is a cappella. It lasts some 90 minutes. I also recently completed a complete setting of the Liturgy of St John Chrysostom, in Greek, for an American ensemble, the St Romans Cappella, which is of course a cappella. But I have also written works for choir and instruments – I have a new piece, for example, The Land Which is Not, which will be performed by the BBC Singers later this month, scored for 24 voices and solo ‘cello, and another example is my Stabat Mater, which includes texts by Anna Akhmatova, and which I wrote for the Oslo Soloists Choir, and is scored for choir and string quartet.

A famous ancestor of John Tavener, the composer and organist of the 16 century, John Taverner, accompanied most of his voice compositions (Mass, Magnificat) by organ. What was John Tavener’s attitude to this western tradition of combination of liturgical singing and organ playing?

No, this is not true. The 16th century John Taverner’s music is also a cappella, though the organ was certainly used in the Roman Catholic Church at that time. Tavener was in fact a very accomplished organist and pianist. In his younger days, he played organ in a Presbyterian church, and later on he still enjoyed improvising on the organ occasionally. Some of his works include organ parts, such as God is with us, and there is a remarkable solo organ work, Mandelion.

Could you please tell us about the composition Ikon of Light, which was performed for the first time in Russia? Was it composed specially for the ensemble The Tallis Scholars? What was the cooperation of John Taverner and this ensemble based on?

Yes, it was written specifically for the Tallis Scholars. It is an extraordinary work, at the same time highly structured and mystical, based on the writings of St Symeon the New Theologian and the idea of light. Tavener’s cooperation with the Tallis Scholars began because he was searching for a new direction in his work after he converted to Orthodoxy, and not only did he go to hear them sing renaissance music, but he began to write new pieces for them, and the first result of this was a recording that included Russian music from the mediaeval period, Rachmaninov, Stravinsky and new music by Tavener himself. Ikon of Light came a little later, and beautifully exploits the vocal qualities of the Tallis Scholars (in combination with a string trio) and allows Tavener’s wonderful melodic invention to flower.

John Tavener described the process of composing in the following way: “I would compare my method of composing to the method of icon-painting”. Does it explain the name he has given to his composition – Ikon of Light?

Yes, during this period he was very concerned with the idea of trying to compose “musical icons”, and a number of his other works are also called “Icon”. It is a difficult thing to do, because of course music is not a precise equivalent to icon painting, and in any case here we are dealing with paraliturgical music, not music written for use in church services. But it led him in very fruitful spiritual and technical directions.

Ikon of Light is a polyphonic composition but at the same time it sounds very much like Znamenny Chant, which is most clearly seen in the solo parts. When speaking about the influence of Russian culture, John Tavener admitted that the tradition of Znamenny Chant had a great effect on his music. Do you feel this kind of influence in his music?

Yes, but not in Ikon of Light! I cannot hear any Znamenny influence in that piece at all. The only chant reference is to Byzantine chant, in the “Trisagion” section. In other works, however, there certainly is an influence of Znamenny chant – I am thinking, for example, of Funeral Ikos, The Great Canon of St Andrew of Crete and especially the Orthodox Vigil Service.

Znamenny Chant is often called icon-painting music, Znamenny Chant has a special austerity, greatness of soul and impassivity in it. Was John Tavener inspired by this monophonic style in creation of his own compositions?

As I said above, there are works that clearly reflect it, and certainly austerity and impassivity were qualities that interested Tavener greatly.

When he was composing Ikon of Light, he was inspired by hymns by Symeon the New Theologian. Do you think that the melodiousness of ancient Greek language played a great role in the success of John Tavener’s composition?

Yes, it is quite clear, especially in the central movement, St Symeon’s Mystical Prayer to the Holy Spirit, that Tavener’s cascading melodic patterns are inspired by both the magnificent of the poetry and the sound of the Greek. He loved the Greek language.

In one of his interviews John Tavener said: «I actually adore the Coptic icons because they have a childlike mentality», and said it is important “to be like children”, that is why he was attracted to the music of American Indians and Sufi music. What did the composer mean by saying about his idea of restoring innocence?

Well, of course, Christ said that we should be like children to accept the Kingdom of Heaven. I think it’s as simple as that. Tavener always sought this innocence, this state of grace that existed before the Fall of Man, and in Orthodox theology this innocence is what has been lost: the image of God has been blurred by mankind, but not entirely lost. We have the possibility of recovering it if we accept the Kingdom as children.

What parts of the Divine Liturgy were most important for John Tavener? He said in one of his interviews that he finds the words of Cherubic Hymn most moving, especially the passage that says: «Let us now lay aside all cares of this life»?

Yes, he often spoke of the Cherubic Hymn, and I think it held special importance for him as an image of crossing the threshold from the earthly to the heavenly.

What parts of the Divine Liturgy are most important for you?

I find that a difficult question to answer, since I am so aware both as priest and musician of the “dramatic curve” of the Liturgy, and find it impossible to remove things from it, but there are clearly points that are “peaks” on this curve, such as the Cherubic Hymn, the Megalynarion (Hymn to the Mother of God) and the Communion Hymn and, in Greek use, the Trisagion, which is not accorded so much musical importance in Russian use.

John Tavener pointed out the fact that Patristic Literature influenced him greatly, especially works by Dionysius the Areopagite, St Isaac the Syrian and St Gregory of Nyssa; he was very much inspired by the words: “God became man because of us. Let us become God because of him.” Why is the intellect is so important in music? As John Tavener said: «Composers have to be highly developed intellectually».

Tavener always recalled the hesychast ideal of the “mind entering the heart”. He did not consider the intellect to be merely a faculty for understanding in the worldly sense, but understood, patristically, the intellective organ to be the heart, by which genuine understanding, and theosis, may come about.