Valery Anatolievich Burkov is known as the last officer to receive the highest distinction in the Soviet Union, the title Hero of the Soviet Union. A professional soldier in the second generation, air combat officer, he lost both legs in the war in Afghanistan, clinically died three times, survived, and returned to combat. In the nineties, he made a brilliant career in politics, worked as a consultant to the President of the Russian Federation, was a member of the Duma. Then, Burkov vanished. Disappeared from public view. There seems to be a gap in his biography from 2009 to 2016. He returned in 2016, but as Monk Kyprian. When asked, what happened during those years, he answers, “I was learning to be a Christian.”

Valery Anatolievich Burkov

Getting ready to meet father Kyprian (Burkov), studying his earlier interviews, listening to the songs of the Afghan war he had written and sung, I think I expected to see someone different. Valery was only tonsured recently, in the summer of 2016, so most of his life he was a military-man, an officer, and a politician.

We saw a man of colossal height, with bright twinkly eyes and a grey beard. Our cameraman kept forgetting himself, he kept trying to get a blessing from father Kyprian as if he were a priest – there was almost nothing worldly left in his appearance. By the way, you would never have thought that father Kyprian has walked on prostheses for over twenty years!

Though monasticism was a logical step in the life of the Hero of the Soviet Union, yet, he is now a different person, very different from the man awarded the highest military distinction, the Gold Star (an insignia worn by recipients of the title Hero of the Soviet Union), in 1991.

War is unnatural

“A person’s path to God goes through the whole life,” says father Kyprian, “Christ said, ‘Behold, I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears My voice, I will come in to him and dine with him.’ (Rev. 3:20) I heard many “knocks at my door” in my lifetime, and obvious ones at that!”

One of the most serious reasons to stop and think, to re-evaluate life was obviously the war.

When he was still a young officer, a graduate of the Chelyabinsk Red Banner Institute of Navigators, he had a nightmare. He dreamt he got blown up on a landmine. “It can’t get any worse than that,” he thought to himself. Burkov told a friend about his dream. “God forbid! I’d rather shoot myself!” said he back then…

1979. The war in Afghanistan begins. Valery’s father, Colonel Anatolii Ivanovich Burkov, sets off for Afganistan as part of a restricted contingent of Soviet troops. In October 1982, news of his death reaches home. While on a mission to rescue the crew of a helicopter that was downed, Burkov, Snr. was hit and went up in flames in his Mi-8 (the crew were saved).

Anatolii Burkov was awarded the Gold Star posthumously.

Valery served since the mid-seventies. A graduate of a military university, he served in the Russian Far East, but after the death of his father he literally forced the army command to send him to Afghanistan, though he could have avoided going on medical grounds. Some thought he sought revenge, but, in fact, having made a promise to his father the last time they spoke.

Father Kyprian can look at war from only one angle – it is not a game, nor a place to flex one’s muscles, it is something terrifying, something completely alien to man.

“When I saw the dead and the wounded in my first offensive, I felt sick, nauseous, it was very unpleasant. War is psychological trauma in any case, because you see death, blood, and tragedy every day. You cannot get used to death, but some sort of inner defence mechanism kicks in, and you begin to look differently at what’s happening. In war, you’re constantly faced with a choice of whether to overstep the moral law implanted in us by God or not.”

Once Burkov did not stand by when he could have, thus saving a man’s life. War is war, they captured a dushman (rebel), who turned out to be no dushman, but a regular Afghan, but to avoid having to drag him along or doubting whether to free him or not (you should never let an enemy go, yet it is also dangerous to take him along), the command decided to get rid of him.

Burkov would not let the battalion commander do it to the immense relief of the soldiers who had been ordered to execute the man. To this day, he considers it to be the only worthwhile act in his whole life and in the war.

Any soldier, says he, hates war:

“No one can hate war more than soldiers do, especially those who’ve experienced fighting. I would not wish it on anyone to participate in combat! War is tough, unnatural.”

Wretched prophetic nightmare

…The nightmare came true in April, 1984. During a Panjshir offensive, the young major got blown up on a land mine. It was mountainous terrain, with great difficulty he was evacuated by helicopter. Awaiting help on top of a cliff, in pain, he thought only of how his mother would take the news. His father had died first, now the son got blown up – how would she bear it?

Military hospital, three clinical deaths, the doctors managed to save the officer’s arm by a miracle, his legs had to be amputated. “In the morning, when I came to after being wounded, my right arm was in a cast, so I lifted up the bed sheet with my left hand and saw the remnants of my legs in a cast. Suddenly, as some kind of icon, there appeared in my mind a vision of Alexei Maresiev, the pilot of the Great Patriotic War who having lost both his legs, returned to flying his jet. I thought, ‘He was a pilot; I am a pilot; and I am a Soviet man, too. Why can’t I achieve what he did?’ And I stopped worrying, ‘It’s going to be fine! They’ll make me new legs!’ Since then I worried no more. I was positive I would stay in the military and return to combat.”

Once, when Burkov was already on prostheses, the very friend in whom he had confided his nightmare came to see him. “So, what now?” – he asked. “Are you going to shoot yourself?” “Of course, not!” That nightmare turned out to be prophetic, and it was a “knock on the door” from the other world, because such coincidences made you think, where did that prophetic communication come from? And the light at the end of the tunnel he saw when he was clinically dead, where did it come from?

– Father Kyprian, – I ask, – Did you ever ask yourself, “what have I done to deserve this?”

– I did ask it in song, but it was more of a metaphor, “Why do gods punish me so? I lay there on the cliff, crucified, grinding my teeth, straining my nerves.” No, I never had those emotions. I made a conscious choice in going to Afghanistan, I knew how serving there might end.

And the military service ended. The father was dead, the son lost limbs, what was it for? Afterwards, Burkov answered his question himself and wrote a song,

And the military service ended. The father was dead, the son lost limbs, what was it for? Afterwards, Burkov answered his question himself and wrote a song,

“So, what can I say, what did I understand?

Yes, for the happiness of youth,

Though they’re from a foreign land,

It is worth to live and die.”

Though in a radio interview, father Kyprian, at that time still Valery Anatolievich Burkov, let it slip that the war in Afghanistan was not necessary and that those who had spent some time there realized it, nonetheless, military service is service to an officer, duty is duty, and both he and his father were raised that way,

“Motherland said, ‘The Afghan people need our help,’ and we went to help the Afghan people.”

I never thought I could weep like that

The Afghan phase of his life was drawing to an end. Father Kyprian says that despite all its horrors the war gave him a kind of inner strength he had never had before. He describes how he re-evaluated his whole life there. He remembers the people who sacrificed themselves there,

“I’ll give you a simple example, more eloquent than any description. It happened during a military operation. According to regulations, our sappers walked before us. All of a sudden dushmani jumped out from behind a mud brick fence and opened fire at them.

“Our commanding officer, the First Lieutenant, with whom we sat around having tea only the day before, got a bullet right in the stomach. The Sergeant walking next to him was shot in the head, half his skull was gone, you could see his brain. And in this condition, he pulled his commander aside and only then he died. Basically, he would not let his commander get killed, but died himself.”

Father Kyprian admits to becoming sentimental after the war – the emotions that were being forcefully contained there came rushing out.

– Did you ever cry? I ask.

– I never cried because of the war or because of anything worldly. But I burst out crying at my father’s funeral when I read his last letter and reached the words, “Do not pity me, mother, I do not suffer, and my life isn’t hard. I’ve been burnt and still am burning, but I will give you no cause to be ashamed of me.” He literally went up in flames in that helicopter. Afterwards, I wept and wept much more before God. I never knew one could cry so much – torrents were coming from my soul, purifying torrents…

It is 1985. Valery Burkov does return to the army after a year spent in hospital. He enrols in the Gagarin Air Force Academy where he meets his future wife Irina.

It is 1985. Valery Burkov does return to the army after a year spent in hospital. He enrols in the Gagarin Air Force Academy where he meets his future wife Irina.

That’s when doubts that had assailed him in hospital dissipated, “I used to think, will girls look at me with this wound? I was single back then. Later on, I found out they still did – they were fine with it!”

They got married after the first year of studies. Answering some journalists’ questions about how long Valery had courted her Irena said, “Are you kidding me! It was I who courted him for six months to prove to him I would make a good wife!” Finally, Burkov gave in and believed her.

Years later, his wife gave her consent to Valery becoming a monk.

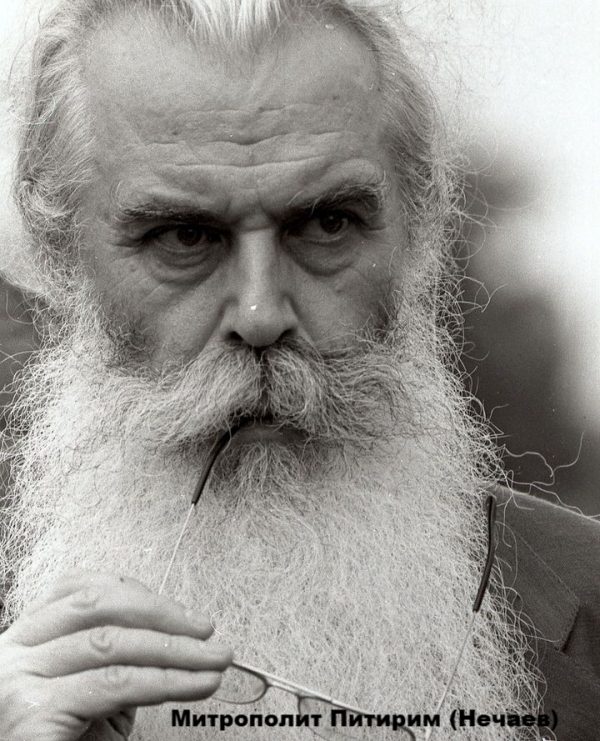

Metropolitan Pitirim and Patriarch Alexy

1991-1992. Valery deals with issues of the disabled as President of the Liaison Committee of the Affairs of People with Disabilities under the President of Russia. From 1992 to 1993 he is the President’s advisor on the issues of persons with disabilities. Russia is very much behind in this sector, they basically had to start from scratch. For example, the current concept “bezbar’ernoe prostranstvo” (access for people with disability) was introduced at that time.

Metropolitan Pitirim (Nechaev)

But the Lord is knocking at the door… Valery heads a delegation heading to a conference in Rome on the issues of people with disabilities. Metropolitan Pitirim (Nechaev) was also part of the delegation. During their free time, His Grace spoke to Valery of Orthodoxy, of its differences from Catholicism, they visited churches, both Catholic and Orthodox, spoke on different topics. Then he got to meet Alexis, Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia, so “the knocking got really loud!”

Then there was another memory, the image of an old lady who once lived next door, dressed in black from head to toe, reading a thick, old Bible.

Valery was about ten at the time, but since then he always really wanted to read that mysterious Bible. But, says he, as usual, there was never enough time, vanity of vanities (Eccl. 1:2)…

“Chocolate covered” on the outside, lonely on the inside

2003. Burkov returns to politics, he heads the party “Rus” at the National Duma elections. In 2008 he becomes a member of the Kurgan regional Duma. Back to doing social work in an attempt to help people.

2009. Burkov has everything that a normal man can dream of. His career is on track – in the Office of the President he is seen as one of the main candidates for governorship. He has a family with a grown son, a vocation, he is successful – all goals are achieved, life seems full. “However, inside, my soul was empty,” recalls father Kyprian. “I had reached a complete dead end in my worldly life, a void, a loneliness, and an absolute disappointment in life, though on the outside I seemed to be “covered in chocolate.”

Online there are some wild stories about his turnaround to the faith: through meeting psychics and then monks; through a poltergeist in his house and a miraculous blessing of the house with holy water from Theophany, fatal to the enemy of the human race; through a car accident. Whereas, actually, according to father Kyprian, he could no longer ignore the “knocking”, because God’s call was too obvious, too personal.

There was a car accident, however: once again he was an inch from death, for the fourth time, and again the Lord saved and protected him. But the accident happened later and, according to father Kyprian, it was obviously demons’ vengeance who wanted him beat up and killed for baptising Muslims…

But back in 2009, even before he lay down his deputyship, Burkov set off on his path to God. Diligently he began studying the New Testament, spiritual literature, the holy fathers. In 2010 he had his first Great Lent and then he says he took a sort of oath of allegiance to the Lord on Pascha.

Father Kyprian speaks of his first confession with irony and laughs at himself,

“I brought a list seven-page long to confession – a fabulous report of the sins committed! I went about it as a military man, as an analyst – all the sins listed by line, pluses, minuses, basically, all as it should be!

“Hieromonk Panteleimon (Gudin) (today, the acting Abbot of the patriarchal metochion in the church of the icon of the Holy Theotokos “Multiplier of Wheat” in the Priazov Stanitsa) who took my confession glanced at my table of sins and said, “Wow, I’ve never seen anything like that before!”

I ended my confession with, “As for pride, I don’t really see it in me…” The hieromonk glanced at me affectionately and smiled, “Don’t worry! The Lord will show you some day.” The following morning, I communed, then went to the church bookstore. The moment I stepped on the threshold I saw a book “Lord, help me rid myself of pride.” I bought it and spent the remainder of the day laughing at myself – I hadn’t seen the forest for the trees!”

For many of the military people he knew it was enough to “have God in their souls.” But it wasn’t enough for him. “To this I always replied, ‘Friend! What makes you think it’s true? Did you at least ask God or did you just stuff Him inside your soul?’

“Many Soviet officers find it hard to switch from something they believed in since their infancy to a new outlook on life. He did switch however, “The obstacle is only internal – we are used to living in a certain way and we do not want to renounce our opinions – there’s nothing else! We’re just too lazy to think. Vanity of vanities!”

“It was hard to renounce one’s false understanding of things. I found myself resisting and doubting every single line of the New Testament: who says Christ is God? Why on earth should I believe this?

“But that is how the Word of God works,” explains father Kyprian. “No matter how much you resist it, deep down you know, the Truth is there!”

Father Kyprian recalls watching a priest on a television talk show for the first time.

He listened and thought, “But why were they executed during the Soviet times? They preach love!”

Another time, the priest, appearing on the show, turned out to be very young, and combat officer Burkov chuckled,

“What could this young priest, this beardless lad, teach me? I’ve been to hell and back. What about him? Rookie, he knows nothing of life!” Yet, I kept on watching and then, “at some point, I felt like a complete idiot with all my life experience compared to this young priest through whom spoke God! A little later I understood that that was because the priest spoke not from himself, but the Word of God, which is where real strength is!”

They are like my children!

2010. Valery Burkov resigns from his deputyship.

He no longer gives interviews, refuses to appear on radio and television shows, “A person getting to know God can no longer be bothered by such vanities.” He started refusing to speak before schoolchildren – something he had got used to during those years – because he no longer knew what to talk to them about. Before he used to speak to them of patriotism, of the love for their homeland, of morality, afterwards he realized it was all meaningless without God, that even love wasn’t love without God, it was nothing but feelings, and feelings tend to change.

Once, they managed to talk him into appearing on television. They said a married couple, war veterans, would appear on the Channel One show coming out on May, 9, Victory day. He agreed only because he had admired war veterans since childhood, because he respected these men of incredible courage, nobility, and patience, hard as a rock. He went there only because of the veterans only to realize that he was a “completely lost cause for television!”

A new phase in his life had begun, “I was discovering God, the Holy Scriptures, I took theological courses, I was adjusting my mind, repenting by any means known.” However, since faith by itself, if it doesn’t have works, is dead (James 2:17), he finds himself a new occupation…

His country house in the suburbs of Moscow becomes some kind of rehabilitation centre for people with serious problems: alcoholics, victims of religious sects, people who dabbed in magic, psychics, as well as people who simply felt lost.

“There were some,” recalls father Kyprian, “who got to the point where they hated everything: Russia, people, children, in short, everything that should have made them happy. Their life was nothing but hatred, it was hell and constant pain. It is not a condition a person reaches easily, they are driven over the edge. As a rule, it all starts with the parent-child relationship, which means, it’s not someone’s fault, but their misfortune… And the only thing that can conquer hatred is love, it’s a long, slow process.”

Oddly enough, even Baptists came, there were quite a few Muslims, of whom twelve got baptised.

“They are all like children to me,” says father Kyprian, “They call me, ‘dad’.”

The former deputy gave them room and board, studied Orthodoxy with them, told them what they should read or listen to, and watched them change,

“I can only marvel at the mercy of God! How much does the Lord change people! Afterwards, they would ring me, ‘Thank you, father Kyprian, everything is different now because of your prayers,” and I would be wishing the ground would swallow me up – what prayers?! I don’t even know how to pray properly. It was obvious to me that the Lord worked the miracle, I was only a transponder.

When a person opens the door to Christ, everything in their life begins to change drastically. People are amazed, and at one time I used to be amazed: when a person opens their heart to God, they become happy! The same thing happened to me: I had felt empty and lonely, then my life was full and happy, and full of enjoyment!”

“They say physical flaws are nothing compared to ‘flaws’ in the soul, ‘What does it matter if I don’t have legs? So, I don’t have any, but I have prostheses. To me personally it doesn’t matter at all. However, what is on the inside, that is what a person’s happiness or misery depends on.”

Seven years went by in this quasi monastic life.

Yet, something was missing… “Obedience was lacking!” says father Kyprian. There was a want of something more, a feeling that something else has to happen in life. There were always anywhere from three to nine people living nearby, whereas he craved solitude.

Is it God’s will that I become a monk?

Schema Archimandrite Ilii (Nozdrin)

Then, suddenly, in 2015, a visit to Elder Ilii (Nozdrin) was organized. The future monk Kyprian did not ask to join in, he was invited. He did not know what to ask father Ilii, but the latter was an Elder, he would probably tell what the will of God was of his own accord. Father Ilii first went up to Konstantin Krivunov, the friend with whom Burkov had come, and said, “Well, you’ll become a priest!”

“Konstantin and I had discussed priesthood before,” recalls father Kyprian. “His answer to my question was ‘You know, Valera, as for the priesthood, I don’t know if I’d be able to handle it, as for a deacon, that I probably could do…”

When Burkov’s turn came, the only thing that the Hero of the Soviet Union could think of was, “Is it God’s will for me to become a monk?” The elder did not reply straight away, but prayed for a minute or two, then slapped him across the head and gave him a blessing.

Half a year went by, and suddenly there is phone call from Hieromonk Makary (Eremenko), dean of the Kazan male hierarchical metochion in the town of Kara-Balta of the Bishkek and Kyrgyzstan Diocese, “Check your email. You have a blessing to become a novice. You will be in charge of the Kyrgyz community in Russia. You will look after religious education and social work.”

And eight months later, in June, 2016, another phone call, “Come during the Apostles’ Fast for monastic tonsure! The Bishop blessed!”

“I thought to myself,” recalls father Kyprian, “My, my! Everything was done without me! But I believe in not refusing anything, except sin, especially when an offer or request comes from a priest, and in not asking for anything myself. Nonetheless, it was very sudden. I was filled with doubt, hoping that maybe they would make me a monk during the following fast…”

It turned out that the Bishop had already signed the ukaz, there was no way of changing the date. So, without any step of his own, Valery first became a novice, then a monk.

And a man who had spent his whole life calling the shots, giving orders, was under another’s authority, gave himself fully in obedience,

“At first, when I read the prayer, ‘Thy will be done, not mine,’ I could not understand it at all, what does it mean? What happens to me now? I always made all my decisions myself and acted upon them. In time, however, I realized there was nothing better than giving yourself up to the will of God and obeying an experienced person. Because no one knows better than God what is best for you!

“You yourself will never be able to arrange your life as God can. And then you act surprised!

“It’s better not to plan anything. Before I actually used to plan everything a year ahead. These days I don’t know what will happen in a few days times and I don’t make plans anymore!”

A monk with a Hero’s star

2016. The day after his monastic tonsure monk Kyprian was blessed to wear his insignia, the star of the Hero of the Soviet Union. He was very surprised! He had thought he was done with his worldly life, and with his insignia as well, as he would no longer have to wear suits. Yet he was told wearing it would be preaching. He could not understand it at first, but during the several months spent travelling across Russia, everything fell into place.

“There is still no solitude, however,” smiles father Kyprian. “I used to think, finally, I get to lock up in my cell and pray, but the Lord willed otherwise.”

He’s been travelling around the country since the autumn of 2016. He admits that even as a politician he spoke less than he does now. It is very different now of course, it is preaching.

And, it seems, studying never ends. A degree in education from St. Tikhon’s University to focus on religious education, a degree in psychology from the Russian Orthodox University to assist the suffering, a course in missionary work – it is hard in Kyrgyzstan without special skills and knowledge. “We must bring light to our Muslim brothers, and it must be done intelligently,” explains father Kyprian.

There are only six monks in the male metochion in Kara-Balta, in Kyrgyzstan. They live in mudbrick cells with wood heaters, father Kyprian fixed one of them up. The conditions are very basic, there is no heating in church. The restoration of the monastery is not going well. It is hard to provide even the most basic conditions for a Sunday school, for a centre of spiritual and psychological help. There is nowhere for people to stay even if they come for one night, there is nowhere to talk to people who come to the monks for help, except their own cells, which is not really proper.

The Hero of the Soviet Union now has to look up old ties and travel to assist the mission in Kyrgyzstan. Father Kyprian describes the Kyrgyz people as simple, kind, and friendly. He never stops marvelling,

“Interesting! In Moscow who did the Lord send me? The Kyrgyz and the Kazakhs, the non-Orthodox. And where did I become a monk? In Kyrgyzstan! This is how the Lord arranges things. I would never in my life have thought that I would end up here. Yet, if I’m here, it means I am needed here.”

Father Kyprian hasn’t forgotten about life completely. He mentions the officers in Syria whom he knows, thinks the new generation of the military is estimable and praiseworthy. Says the attitude towards the army has changed, has improved. Many people are now vying for admission to military schools and to serve under contract.

“What is the most important thing for a military man? The home front, to know that if he dies at war, his family will be taken care of. In that case, there is no fear of death, because your family is your homeland.”

These days the most important thing in his life has nothing to do with either politics, or the army, or social work,

“Preaching is the most important thing, impressing upon hearts, “Love the Lord with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind, with all your might, and your neighbour as yourself.

“The centre of a person’s life is love. God is love, and he who abides in love, abides in God, and God in him. Where there is no love, there is no God.”

In 1992, when Valery was in hospital, he heard the expression, “faith moves mountains.” And these words gave him strength, helped him remain optimistic. These days…

“These days,” says father Kyprian, “I do not believe, I know! I am simply a person who knows and who became convinced through knowledge that everything will be well for those who love the Lord. While those who reject Him, are in hell already – those are the people that come to me.”

Burkov’s war still hasn’t ended, but it is a very different kind of war. “Being in the military is nothing compared to monasticism!” smiles the retired Colonel, the new monk. Internal war and battling the spirits of evil is a lot harder,

“Let me tell you something. There are three kinds of endeavour: in war, in the world, which is everyday life, and monastic endeavour. I have experience in all three. I went to war, I lived in the world and was married, now I am in a monastery.

“Let me tell you something, monastic endeavour is much harder than the others. I would rank it as the hardest! Yet I’d rank it as the most joyful as well… They say if people only knew how hard it can be in monasticism, nobody would become a monk. But if they knew what joy belongs to monks, everyone would become monastics.”

Prepared by Valeria Mikhailova. Video, photo by Viktor Aromshtam. Photos used in preparation of the article eparchia.kg, Sputnik, mil.ru, shadrinsk.info, museumnahimov.ru, optina.ru, Газета.ru

Translated from the Russian by Maria Nekipelov