One day Jesus asked the question, “Do people gather figs from thistles?” The answer is of course no––you harvest what you plant. Plant thistles and thistles take root and thistles they become. If you want to grow figs, you need to start with fig seeds. With this question, Jesus implicitly ridicules the idea that good can be brought about by evil means. Violence is not the means of creating a peaceful society. Vengeance does not pave the road to forgiveness. Spousal abuse does not lay the foundation for a lasting marriage. Rage is not a tool of reconciliation.

Yet, while figs do not grow from thistles, in the world of human choice and action, a positive change of attitude and direction is always a possibility. Sinners are the raw material of saints. The New Testament is crowded with accounts of transformations.

Yet, while figs do not grow from thistles, in the world of human choice and action, a positive change of attitude and direction is always a possibility. Sinners are the raw material of saints. The New Testament is crowded with accounts of transformations.

In the Church of the Savior in the Chora district of Istanbul, there is a fourteenth-century Byzantine mosaic that, in a single image, tells a story of an unlikely transformation: the conversion of water into wine for guests at a wedding feast in the village of Cana. In the background Jesus––his right hand extended in a gesture of blessing––stands side by side with his mother. In the foreground we see a servant pouring water from a smaller jug into a larger one. The water leaves the first jug a pale blue and tile-by-tile becomes a deep purple as it reaches the lip of the lower jug. “This, the first of his signs, Jesus did at Cana, in Galilee, and manifested his glory; and his disciples believed in him.”

This “first sign” that Jesus gave is a key to understanding everything in the Gospel. Jesus is constantly bringing about transformations: blind eyes to seeing eyes, withered limbs to working limbs, sickness to well being, guilt to forgiveness, strangers to neighbors, enemies to friends, slaves to free people, armed men to disarmed men, crucifixion to resurrection, sorrow to joy, bread and wine to himself. Nature cannot produce figs from thistles, but God is doing this in our lives all the time. God’s constant business in creation is making something out of nothing. As a Portuguese proverb declares, “God writes straight with crooked lines.”

The convert Paul is an archetype of transformation. Paul, formerly a deadly adversary of Christ’s followers, becomes Christ’s apostle and his most tireless missionary, crisscrossing the Roman Empire, leaving behind him a trail of young churches that endure to this day. It was a miracle of enmity being turned to friendship, and it happened in a flash of time too small to measure, a sudden illumination. Witnessing the first deacon, Stephen, being stoned to death in Jerusalem must have been a key moment in setting the stage for Paul’s conversion.

Peter is another man who made a radical about-face. Calling him away from his nets, Christ made the fisherman into a fisher of men. At the Garden of Gethsemane, the same Peter slashed the ear from one of those who had come to arrest Jesus. Far from commending Peter for his courage, Jesus healed the wound and commanded Peter to lay down his blood-stained weapon: “Put away your sword for whoever lives by the sword shall perish by the sword.” For the remainder of his life, Peter was never again a threat to anyone’s life, seeking only the conversion of opponents, never their death. Peter became a man who would rather die than kill.

How does such a conversion of heart take place? And what are the obstacles?

It was a question that haunted the Russian writer Leo Tolstoy, who for years struggled to turn from aristocrat to peasant, from rich man to poor man, from former soldier to peacemaker, though none of these intentions was ever fully achieved. As a child Tolstoy was told by his older brother Nicholas that there was a green stick buried on their estate at the edge of a ravine in the ancient Zakaz forest. It was no ordinary piece of wood, said Nicholas. Carved into its surface were words “which would destroy all evil in the hearts of men and bring them everything good.” Leo Tolstoy spent his entire life searching for the revelation. Even as an old man he wrote, “I still believe today that there is such a truth, that it will be revealed to all and will fulfill its promise.” Tolstoy is buried near the ravine in the Zakaz forest, the very place where he had sought the green stick.

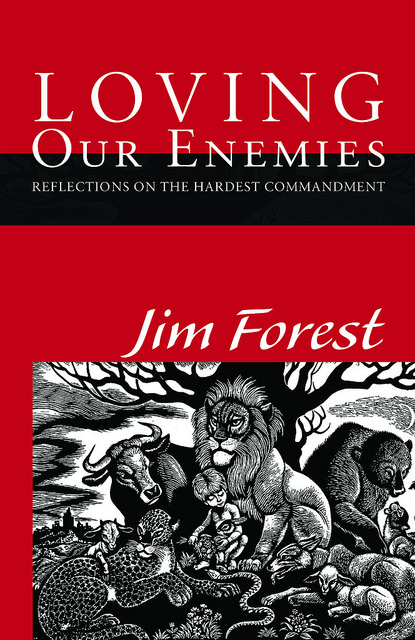

Were we to discover it, my guess is that the green stick would probably turn out to bear a three-word sentence we have often read but have found so difficult that we have reburied it in a ravine within ourselves: “Love your enemies.”

Twice in the Gospels, first in Matthew and then in Luke, Jesus is quoted on this remarkable teaching, unique to Christianity:

You have heard that it was said you shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy, but I say to you love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father who is in heaven; for he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust. For if you love those who love you, what reward have you? Do not even tax collectors do the same?

Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you. To him who strikes you on the cheek, offer the other also; and to him who takes away your cloak, do not withhold your coat as well. Give to everyone who begs from you; and of him who takes away your goods, do not ask them again. As you wish that others would do to you, do so to them.

Perhaps we Christians have heard these words too often to be stunned by their plain meaning, but to those who first heard Jesus, this teaching would have been astonishing and controversial. Few would have said “amen.” Some would have shrugged their shoulders and muttered, “Love a Roman soldier? You’re out of your mind.” Zealots in the crowd would have considered such teaching traitorous, for all nationalisms thrive on enmity. Challenge nationalism, or speak against enmity in too specific a way, and you make enemies on the spot.

Nationalism is as powerful as an ocean tide. I recall an exchange during the question period following a talk opposing the Vietnam War that I gave in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, back in 1968. I had recently been involved in an act of war resistance that would soon result in my spending a year in prison, but for the moment I was free on bail. During the question period, an angry woman holding a small American flag stood up and challenged me to put my hand over my heart and recite the Pledge of Allegiance. I said that flags ought not to be treated as idols and suggested instead that all of us rise and join in reciting the Our Father, which we did. Her anger seemed to recede a bit but I suspect in her eyes I was a traitor. I had failed her patriotism test.

We tend to forget that the country in which Jesus entered history and gathered his first disciples was not the idyllic place Christmas cards have made of it, a quiet pastoral land populated with attractive sheep, colorfully dressed shepherds and tidy villages crowning fertile hilltops. It was a country enduring military occupation in which most Jews suffered and where anyone perceived as a dissident was likely to be executed. In Roman-ruled Palestine, a naked Jew nailed to a cross was not an unfamiliar sight. To Jesus’ first audience, enemies were numerous, ruthless and close at hand.

Not only were there the Romans to hate, with their armies and idols and emperor-gods. There were the enemies within Israel, not least the tax collectors who extorted as much money as they could, for their own pay was a percentage of the take. There were also Jews who were aping the Romans and Greeks, dressing––and undressing––as they did, all the while scrambling up the ladder, fraternizing and collaborating with the Roman occupiers. And even among those religious Jews trying to remain faithful to tradition, there were divisions about what was and was not essential in religious law and practice as well as heated arguments about how to relate to the Romans. A growing number of Jews, the Zealots, saw no solution but violent resistance. Some others, such as the ascetic Essenes, chose the strategy of monastic withdrawal; they lived in the desert near the Dead Sea where neither the Romans nor their collaborators often ventured.

No doubt Jesus also had Romans and Rome’s agents listening to what he had to say, some out of curiosity, others because it was their job to listen. From the Roman point of view, the indigestible Jews, even if subdued, remained enemies. The Romans regarded this one-godded, statue-smashing, civilization-resisting people with amusement, bewilderment and contempt––a people well deserving whatever lashes they received. Some of those lashes would have been delivered by the Romans in blind rage for having been stationed in this appalling, uncultured backwater. Judaea and Galilee were not sought-after postings for Roman soldiers––or for the Roman Prefect at the time, Pontius Pilate.

Jesus was controversial. Not only were his teachings revolutionary, but the more respectable members of society were put off by the fact that many drawn to him were people who had lived scandalous lives: prostitutes, tax collectors, and even a Roman officer who begged Jesus to heal his servant. The Gospel says plainly that Jesus loved sinners, and that created scandal.

Many must have been impressed by his courage––no one accused Jesus of cowardice––but some would have judged him foolhardy, like a man putting his head in a lion’s mouth. While Jesus refused to take up weapons or sanction their use, he kept no prudent silence and was anything but a collaborator. He did not hesitate to say and do things that made him a target. Perhaps the event that assured his crucifixion was what he did to the money-changers within the Temple precincts in Jerusalem. He made a whip of cords, something which stings but causes no wounds, and set the merchants running, meanwhile overturning their tables and scattering their coins. Anyone who disrupts business as usual will soon have enemies.

Many devout people were also dismayed by what seemed to them his careless religious practice, especially not keeping the Sabbath as strictly as many Pharisees thought Jews should. People were not made for the Sabbath, Jesus responded, but the Sabbath made for people. Zealots hated him both for not being a Zealot and for drawing away people who might have been recruited. Those who led the religious establishment were so incensed that they managed to arrange his execution, pointing out to the Romans that Jesus was a trouble maker who had been “perverting the nation.” It was the Romans who both tortured Jesus and carried out his execution.

Any Christian who believes Jesus to be God incarnate, the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, who entered history not by chance but purposefully, at an exact moment and chosen place, becoming fully human as the child of the Virgin Mary, will find it worthwhile to think about the Incarnation happening just then, not in peaceful times but in a humiliated, over-taxed land governed by brutal, bitterly resented occupation troops. Jesus entered by birth, lived in, and was crucified and raised from the dead in a land of extreme enmity.

Transposing Gospel events into our own world and time, many of us would find ourselves alarmed and shocked by the things Jesus said and did, for actions that seem admirable in an ancient narrative might be judged unwise and untimely, if not insane, if they occurred in equivalent circumstances here and now. Love our enemies? Does that mean loving criminals, murderers, and terrorists? Call on people to get rid of their weapons? Apprentice ourselves to a man who fails to say a patriotic word or wave a single flag? Many would say such a man had no one to blame for his troubles but himself.

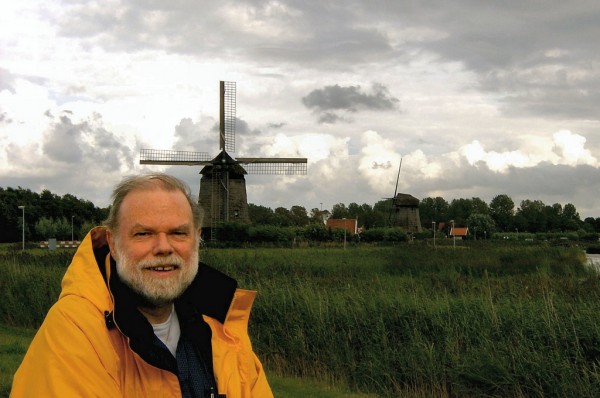

It was a big step, and a risky one, to become one of his disciples. Had you lived in Judaea or Galilee when the events recorded in the Gospel were happening, are you sure you would have wanted to be identified with him? IC