A sermon preached by Father Michael Harper in St Botolph‟s Church, Bishopsgate, February 19th 2006

Introduction

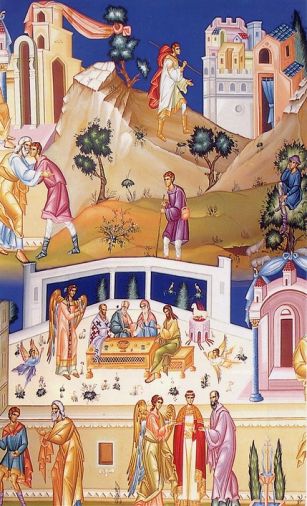

The parable of the prodigal son is the best known of all Christ‟s parables. If is very different, for example, from the parable of the unjust steward that follows it (in chapter 16), which reflects Middle Eastern business life, and which is very hard for westerners to understand. But the parable of the prodigal son, although as we shall see it has eastern nuances, is about family life, and so much easier to understand and appreciate. It has been called “the Evangelium in Evangelio” and so it is – the “gospel within the gospel”..

Kenneth Bailey in his book Through Peasant Eyes, write of this parable, “nearly everyone has a sense of awe at its inexhaustible contents”.

This parable is not an allegory, for the father is not “God incognito”. Yet the father in this story is a profound symbol of God the Father.

In some ways the parable has been misnamed, it should perhaps be called the parable of the elder son. Surely the punch line of the story comes at the end with the conversation between the father and his elder son. We are also told about the audience which was composed of a mixture of tax collectors, sinners and Pharisees. The Pharisees were disputing about Christ sitting at table with those they regarded as the riff-raff of society. Their attitude matched that of the elder brother when his brother returned.

The parable is a superb introduction to Lent, because the centre point of it concerns repentance. It is to challenge, so to speak, our preference for the equivalent of feeding on pig‟s swill rather than to dine at our father‟s table. Lent should be for us a change of direction. It is a return to the Father who has been waiting patiently for us to come.

The Love of the Father

Nearly sixty years ago I made an important discovery about this parable. I found that whenever I read it, or heard a sermon on it, there was always something new to learn. I have to admit that when I started preparing for this, I wondered, “does the magic still work?” Well, I am glad to say the answer was “yes”.

I want us to see two aspects of the Father‟s love, and it is the first that came fresh to me. For we see this love in the father‟s response to the demand of his son to share the inheritance with him.

Kenneth Bailey describes this as “unbelievable love”. He has lived much of his life in the Middle East and North Africa. In his book he describes a period of fifteen years during which he travelled from Morocco to India and from Turkey to the Sudan, asking villagers the same question, “do you know of anyone who has asked his father for the inheritance while the father is still alive.” Here is the conversation which was repeated over and over again:

“Has anyone ever made such a request in your village?”

“Never”

“Could anyone ever make such a request?”

“Impossible!”

“If anyone ever did, what would happen?”

“His father would beat him, of course!”

“Why?”

“This request means – he wants his father to die!”

L Levison writing about this says, “there is no law or custom among the Jews or Arabs which entitles the son to a share of the father‟s wealth while the father is still alive”.

To sum up, Kenneth Bailey writes, “it is difficult to imagine a more dramatic illustration of the quality of love than this”.

An Arab, Ibrahim Said, who has written a commentary on this Gospel has written about this, “this action is unique, something which has not been done by any father in the past”.

The second aspect of the love of the Father which I want us to look at is the demonstration of it when his son returns.

The father is said to be “filled with compassion”. The Greek word (splanchna) literally refers to the bowels – the very centre of our being. Hence the way the word “guts” is used in English. This love is not primarily mental or emotional, but comes from the father‟s total being.

We also read that the father RAN to meet his son. There may well have been a practical reason for this – the desire to be there before the villagers, who might have given the prodigal short shrift. But Kenneth Bailey states clearly that “an oriental nobleman in flowing robes never runs anywhere.” In the East it is regarded as humiliating. The Greek philosopher Aristotle once wrote, “great men never run in public”. But the father did – as a demonstration of the intensity of his love for his son.

But more evidence of that love and acceptance follows:

– The kiss of reconciliation

The Greek word means to kiss “again and again”. It was not a ceremonial peck, but an outpouring of affection. In eastern villages to this day the kiss was the traditional sign of the end of a dispute.

– The best robe

No doubt this was his father‟s own robe, and so demonstrated his father‟s full acceptance of him.

– The ring, which meant “you are trusted”

– The shoes, which signified that he was a freeman, not a slave.

– The fatted calf, which showed that the whole village community was involved, not just the close family.

In the early church confession was normally made to the community not privately to a priest. So here the reconciliation of the father and son is seen not merely as a private and individual matter; everyone in the neighbourhood was also involved.

There is a story told about another “prodigal” who left his home and led a dissolute life, which was a disgrace to his parents. He too decided to go home, but he was uncertain what the response would be. So he wrote to his parents to tell them what he was intending to do. And he asked them to put a small white handkerchief in the top left corner of a window as a sign that he would be accepted back.

As he drew near to his home he looked carefully for the hankerchief. It was not there – but in its place was a huge white sheet; the message was plain, you are welcome home and all is forgiven.

So it is with God‟s love for us. Yes, God does part with the inheritance if that is what we want; but when we come home the response is overwhelming – there is no period of probation, no regime of penances, and no tagging. Total acceptance – no questions asked.

In the Orthodox service of Matins for the Sunday of the Prodigal Son we read: “God restores all the signs of glory”.

The Repentance of the prodigal

We see this in two main steps. First of all we are told that:

“He came to himself”

This is not repentance, and the normal Greek word for repentance – metanoia is not used. In the Syriac version we read “he came to his nefesh”, which is certainly not the word for repentance. The words “he came to his senses”, although not accurately translating the Syriac, is probably as close as we can get in English to what is being said.

It would seem important as we approach Lent that we realise our need to be arrested by it, and to realise fully the seriousness of our condition. The prodigal began to change when he realised where he was and how he needed to go home.

Then we are told that he rehearsed what he was going to say to his father:

“I have sinned against heaven and before you”.

We notice again the connection between God (heaven) and the community, symbolised by his father. Both are to be joined together.

Our sins against God are also sins against the community.

The response of the elder brother.

The German theologian Helmut Thielicke has written a book called The Waiting Father. In it he makes an interesting suggestion. What would have happened if the prodigal had met his elder brother before he met his father. He might well have gone back to the far country.

Ibrahim Said writes, “the elder brother has been living in the house with the spirit of a slave, not with the familiarity of a son”.

How often it must be that people never get to meet God because they meet elder brothers. Some years ago I was travelling on a Lebanese airliner and talking with one of the stewards. I asked him the question “are you a Muslim or a Christian?” His reply was “neither, I‟ve had to live through the Civil War.”

St Paul writes that “because you are children, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts crying „Abba! Father! So you are no longer a slave but a child, and if a child then also an heir through God” (Gal 4:6-7).

The elder brother, although he was living at home, had the spirit of a slave; on the other hand his brother was ready to be a slave in his father‟s house, but was treated by his father as a son.

Let us allow the Holy Spirit to give us that Spirit of Sonship, which will bring us from the far country to the Father‟s love and presence.

Source: Antiochian Orthodox Deanery of the United Kingdom and Ireland