If we go to the local bookstore and open up a biography of a famous man and turn to the first chapter, we will almost always encounter a story of that specific person’s early life. It will begin with him, end with him and take on hundreds of pages about him. Historians can write thousands of pages on one person, with that person being the center of attention at all times.

How odd it is to the modern age that when we open the Life of Saint Mary of Egypt and the story begins with a monk named Zosimus. Where is Mary of Egypt? So humble is this great saint and mother, that even in the story of her life, she hides from us until nearly four pages in. Maybe Saint Mary offers us a call during this season of lent: a call to humility! And not humility for the sake of pride, or for the sake as appearing holy to others. No, not at all. The monk Zosimus revealed to us the life of Saint Mary of Egypt to teach us to be humble for the sake of our salvation. For as Saint Mary teaches us holiness is revealed to us to show us the pathways to salvation, not for our own glory.

Why in the middle of our Lenten journey on the 5th Sunday of Lent do we focus on this story of Saint Mary of Egypt? Humility is almost too easy an answer. Saint Mary of Egypt’s example is a cure to a double-edged sword. In the fires of Lent there is a temptation to feel exalted and proud if we are championing the hardships of spiritual battle; and then there is also the temptation of lamenting and shedding tears over our failures to follow both the physical and spiritual demands of Great Lent.

Yet if we examine the life of Saint Mary, we will see the remedy for these problems. Her story begins with the great monk and elder Zosimus. He is a man who has nearly reached perfection. He almost never eats, and when he does, it is bread and water. He has attained the gift of unceasing prayer. He prays in his sleep, when he works, when at Church, when alone. He keeps all the fasts. He is revered as a great monk. He has more spiritual children than anyone else around him. He is a great man, according to men. But God has more plans for him, and aims to show Zosimus, for the sake of his salvation, a soul who is so high up the spiritual ladder that her body takes flight in prayer. God aims to show Zosimus the saint who hides in humility and repentance.

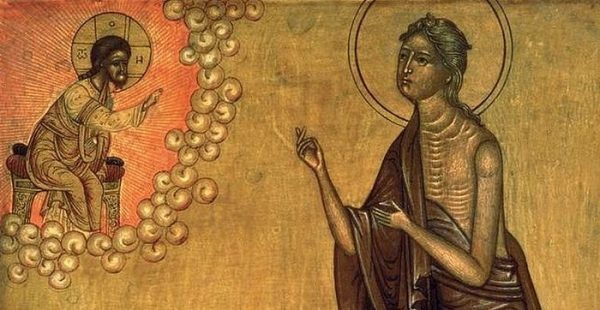

Zosimus follows God’s call to leave his monastery and his native land and to enter into a new monastery. He finds even deeper spiritual rigor, but as the story says, the rigor is not what will save him here. It is the journey he will take into the desert, which is part of the monastic rule at his new home. After journeying into the desert to accomplish what few in the spiritual life have ever done, Zosimus finds himself face to face with a woman so transfigured, so holy, so sanctified and purified of all evil, that she can recognize his priesthood and his whole person without ever having met him.

But who is this woman? Was she, like Zosimus, a monastic since her youth? Has she read through the scriptures dozens of times? Has she been reared by great spiritual fathers and trained in the catechetical schools? Do people come from around the world to seek her spiritual guidance? No. She is a penitent who wanders the desert. She is dead to the world. She seeks the favor of no man. She lives in secret. She begs forgiveness. She has no books. She has no people of this world to teach her. And even more, she is not from the ranks of monastics. She was, in her former days, from the rank of harlots.

In her own words she tells Abba Zosimus that she lived for debauchery. Every corruption and abuse was, in her former life, the source of her joy. There was no sin of fornication she did not commit. And these things were not even done for a profit—she did not charge a fee. But even when she followed young Christian men to tempt them and lead them into darkness, God did not abandon her. As she tells us, God was seeking her repentance and salvation even in her darkest, most despicable moments. Alone in the desert, God and the Theotokos became her teacher—delivering to her scripture and wisdom. And from the tutoring and warm embrace of the Theotokos, Saint Mary of Egypt was formed in the desert to be the greatest of repentants and the greatest of Christians.

In the life of Saint Mary of Egypt, we are given a small glimpse of what it looks like to draw near to “God’s time.” When the world looked at Mary the Egyptian, they saw a harlot, a prostitute, a grifter and a lowlife. Yet when God looked at her, he saw deep in the heart of Mary potential to become the greatest of saints. Mary was not the harlot to God, she was the great repentant who, despite all her former voluntary sin, attained a heart of virginity so pure that she was transfigured into a holy mother of virtue and miracles.

This is the message given to us today. That God’s mercy turns harlots into saints, his forgiveness grants prostitutes hearts of virginity, and that the Mother of God chooses the likes of Saint Mary of Egypt—the likes of those who hide from glory, fame, pride, exaltation. Those who are lowly, those who are cast away by the world, those are the ones chosen to be taught and nurtured by the Theotokos, as she did Christ, to prepare us for the judgement day when we shall meet God.

So, when we leave the doors of the Church, let us not be built up by the pride of our fasting or discouraged in our struggle to maintain it. Let us return into the world seeking repentance and a newness of life. Let us seek the virginity and innocence of the spiritual life in Christ. Let us look upon each other and even strangers, or those who we rank as our enemies, as saints being formed in the fire of struggle, who will one day intercede for us and help us reach the kingdom of God. Let us hide from the passions as Saint Mary hid from the world. Grab onto the coat tails of Saint Mary of Egypt, and let us all together reach the great humility and repentance that allows us to resist pride and embrace tears of repentance.