For most of the twentieth century, western psychology has made observations on the basis of trends that can be repeatedly confirmed in the readily available population of American, white, middle-class college students. Some of these observations make a lot of sense in a world where individualism, achievement, self-esteem, and personal rights are upheld as primary values that guide thought and action. In terms of forgiveness, psychologists who’ve studied the phenomenon have found that the severity of the offense as well as the presence or absence of an apology contribute to one’s ability to forgive. Blake M. Riek and Eric W. Mania, in their article, “Antecedents and Consequents of Interpersonal Forgiveness,” have noted that “the severity of the offense has a significant impact upon forgiveness, such that more severe transgressions are more difficult to forgive.” The authors also found that the presence of an apology greatly increases the chances of forgiveness: “As perceptions of an apology increased so did participants’ level of forgiveness toward the offender.”

From a purely psychological perspective in a world of individualistic values this explains everyday behavior rather well. However, if we enter into a world with values deeper than life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, we find other possibilities that can make it easier to forgive, approaches that focus not so much on the offender and the offense as on the heart of the person who is offended. Ultimately, this is more helpful since we are never able to control the actions of others. However, we do have a modicum of control over our own thoughts and attitudes, which exert powerful leverage on our actions.

From a purely psychological perspective in a world of individualistic values this explains everyday behavior rather well. However, if we enter into a world with values deeper than life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, we find other possibilities that can make it easier to forgive, approaches that focus not so much on the offender and the offense as on the heart of the person who is offended. Ultimately, this is more helpful since we are never able to control the actions of others. However, we do have a modicum of control over our own thoughts and attitudes, which exert powerful leverage on our actions.

In her article entitled “Interpersonal Forgiveness from an Orthodox Perspective,” Elizabeth Gassin writes, “An important prerequisite to forgiveness is coming to terms with one’s reaction to the offense. Orthodox thinking emphasizes how the passions, especially pride and anger, impede our struggle to forgive, and how the virtues can facilitate offering forgiveness. Several Orthodox writers claim that a lack of forgiveness is due to pride (Alekseev, 1996; Aleksiev, trans. 1994; Archimandrite Sophrony, 1974; Staniloae, trans. 1982). Pride involves several elements, such as ascribing goodness to self rather than God (John Cassian, trans. 1979), assuming one ‘knows better’ than others (most profoundly illustrated in Eve and Adam’s disobedience to God’s command), and refusing to see one’s own sin.”

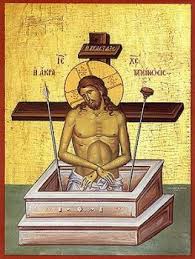

The presence of angry pride and the absence of peaceful humility are important, if not well-known, considerations for discussing human forgiveness. They situate the problem in the context of spiritual warfare, the perfection of the soul, and the imitation of Christ in which the person who loves and forgives becomes united with the Savior and all the Saints. This blessed context is obviously quite different from that of contemporary North American psychological models, which in placing such emphasis on the psychological antecedents of severity and the presence of an apology turn the issue of forgiveness into another forum for the issue of justice. These two antecedents in particular assume that the human scales of justice are operative when any discussion of forgiveness arises.

An anonymous author commenting on the great Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky and his disdain for western moral concepts and the tendency to divide humans into categories of good and bad writes, “The first significant observation is that by demolishing morality which differentiates people into good and evil, Dostoevsky undermines the arrogance of humanism, which believes that with morality, it can eradicate evil from the world. In this manner, Dostoevsky theologizes patristically: the salvation of man cannot come from man himself, but only from God. Secondly, by recognizing in every person the coexistence of good and evil, Dostoevsky invites everyone to refrain from censuring other people and concentrate their interest and their care on their own sins. That way, they simultaneously attain repentance and love. Dostoevsky thus moves within the spirit of the Gospel, but also of the neptic Fathers (“grant me, O Lord, that I might see my own trespasses, and not pass judgment on my brother” – a prayer by Saint Ephraim).”

In this Eastern conception of the psychological antecedents to forgiveness, humility is the lynchpin. Gassin writes emphatically, “Humility can be defined as the opposite of those elements that constitute pride, as defined above. In addition, an etymological analysis of the word in various languages sheds light on the meaning of this virtue. The Latin root of the English word for humility, humus, calls to mind soft soil. Perhaps this refers to the fact that humble people think of themselves as lowly (Mother Alexandra, 1983) or may also be connected to the parable of the good soil (Matthew 13:1-9). According to this parable, a humble person eagerly receives and nourishes the “seeds” that God has planted. The Russian word for humility, smirenie, is lexically connected to reconciling oneself to something, such as to God’s will in the case of a Christian, and/or to acting with peace (Fr. K. Podlosinsky, personal communication, October 1998). Although some western models have noted the role that humility can play in forgiveness (e.g., Enright et al., 1991, 1996; Sandage, 1999; Worthington, 1998), an Orthodox perspective would emphasize this virtue much more strongly than has been done in most scholarly writings to date.”

For the humble, the severity of the offense and the existence of an apology are extraneous factors in terms of one’s willingness to forgive. This new perspective on forgiveness offers freedom (a favorite theme of Dostoevsky) in that the one offended has the power to forgive in each and every circumstance and is not constrained by such factors as the severity of the offense or the presence of an apology. It is a freedom based on knowing who we are, what God has done for us, and what we desire to give Him in return. Always aware of the ten thousand talents that we owe God, always aware that He has forgiven us with His grace and loving kindness, always aware that all of us will stand together one day before our Maker, we come to understand what ultimately matters is not so much what was said to us or done to us, but our faithfulness to Christ’s love, our imitation of His forgiveness, and our humility before the weaknesses of others.