But perhaps “moral” is the wrong word; maybe moralistic would be a better term to use. These days, one has only to light up a cigarette to be met with jeers and contemptible looks or harsh criticism. If one has a momentary lapse and succumbs to one passion or another, or shows any sign of weakness, he is likely to be condemned forever as a bad person. Our so-called “immoral” society is ready to condemn all manner of sin (or should I say sinners), even if that is a word that would not so readily be used. And of course that would not be the preferred nomenclature. For sin can be forgiven, but moralists are not keen on forgiveness: they are more interested in passing judgement.

From a moralist point of view, the rich young man in today’s Gospel reading was a “good person”: he had no addictions, he was not sexually immoral. He was the archetypal law-abiding citizen and religious goody two shoes. Yet deep down he knew this was not good enough. So he approaches Jesus asking what he must do to have eternal life, and he does so by addressing Jesus as “Good Master!” Our Lord’s reply is surprising: “Why do you call me good? Only God is good”. This answer alone could be the basis of a lengthy theological treatise about the divinity of Christ, His relationship to the Father and the meaning of being the Son of God. But maybe I will attempt that another time. For the purpose of this lowly sermon, our Lord’s reply forms the foundation of Christian “morality”: only God is good, because to be truly good is not to be “law-abiding”, but to be holy and the embodiment of love.

Despite this response, Christ then condescends to the moralistic mind-set of the young man, and tells him if he wants to be saved to keep the commandments. As if he is trying to narrow down the list to a few bare essentials, he asks which ones. And our Lord lists a few, including an injunction that is not one of the “Ten Commandments”, but which is to be found in Leviticus 19:18: “You shall love your neighbour as yourself”. The young man replies, “I have done all of this since my youth. What am I still lacking?” Here the inadequacy of morality is made abundantly clear: despite keeping God’s law, he knows salvation is still far off: something is wrong, and he cannot quite put his finger on it.

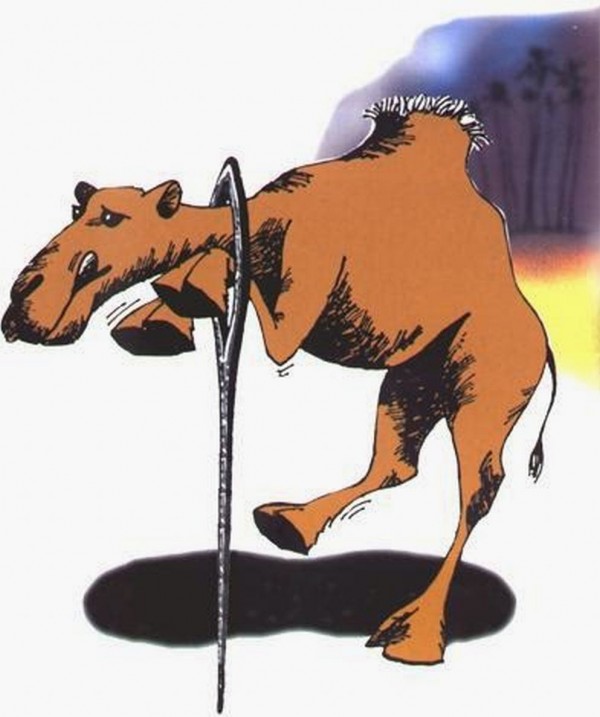

St. Basil the Great’s sermon on this passage is particularly interesting, because it reveals that the young man did not in reality keep the last commandment mentioned: “love your neighbour as yourself”. This is apparent from the vast wealth which the young man possesses while surrounded by people who are poor and starving. As St. Basil explains, “whoever loves his neighbour as himself does not possess more than his neighbour”. If we truly had that kind of love, we would all give what we do not need to those who have less. Therefore our Lord tells the young man that if he wishes to be perfect he should sell his possessions and give the money to the poor, and then follow Him (following Him would have meant living as He and the apostles did: poor and homeless). This the young man cannot accept, and he walks away. He turned down the offer of salvation in order to hold on to his abundant wealth.

The rich young man was moral, but he lacked love. He kept the commandments as religious obligations, as moral rules. He did not kill, he did not steal. but he was NOT a good person. For goodness and selfishness are mutually exclusive, and this man was certainly selfish, since he was unwilling to let go of a life of luxury and privilege to help his fellow human beings.

This is what we are all lacking. We may keep the fasts; we may pray; we may be sexually chaste; we may not smoke or drink to excess; we may not be gluttons; we may not be thieves and murderers, but we are still far from the Kingdom of Heaven, because we do not have love. But worst of all: we do not even have the humility to believe that we are really lacking anything. In this sense, we are worse than the rich young man, because he at least realised that something was amiss.