“So, what’s so special about Lazarus Saturday?” asked my kids, meaning: “So why do we have to go Liturgy twice this weekend?” It’s a legitimate question. One should know these things as an Orthodox Christian.

I will live and survive

By Irina Ratushinskaya

I will live and survive and be asked:

How they slammed my head against a trestle,

How I had to freeze at nights,

How my hair started to turn grey…

But I’ll smile. And will crack some joke

And brush away the encroaching shadow.

And I will render homage to the dry September

That became my second birth.

And I’ll be asked: ‘Doesn’t it hurt you to remember?’

Not being deceived by my outward flippancy.

But the former names will detonate my memory –

Magnificent as an old cannon.

And I will tell of the best people in all the earth,

The most tender, but also the most invincible,

How they said farewell, how they went to be tortured,

How they waited for letters from their loved ones.

And I’ll be asked: what helped us to live

When there were neither letters nor any news – only walls,

And the cold of the cell, and the blather of official lies,

And the sickening promises made in exchange for betrayal.

And I will tell of the first beauty

I saw in captivity.

A frost-covered window! No spy-holes, nor walls,

Nor cell-bars, nor the long endured pain –

Only a blue radiance on a tiny pane of glass,

A cast pattern- none more beautiful could be dreamt!

The more clearly you looked the more powerfully blossomed

Those brigand forests, campfires and birds!

And how many times there was bitter cold weather

And how many windows sparkled after that one –

But never was it repeated,

That upheaval of rainbow ice!

And anyway, what good would it be to me now,

And what would be the pretext for the festival?

Such a gift can only be received once,

And perhaps is only needed once.

(Irina Ratushinskaya, the Ukrainian poet and dissident, was sentenced to 7 years jail in Mordovia in 1983 for “anti Soviet agitation and propaganda”. In prison, she wrote poetry in miniscule script on cigarette papers or bars of soap which she later dissolved in water after memorizing the verses.)

“So, what’s so special about Lazarus Saturday?” asked my kids, meaning: “So why do we have to go Liturgy twice this weekend?” It’s a legitimate question. One should know these things as an Orthodox Christian. And I’m pretty sure I was all over it ten years ago, when learning to adjust to this ancient faith was like a full-time occupation. Somewhere along the line, however, I fell wholly into the rhythm of the life of the Church and those hyper-vigilant inquiries naturally quieted. I just got down to the business of showing up whenever services were scheduled, because that’s what I do now: Show up “as is”, both when I feel like it and when I don’t.

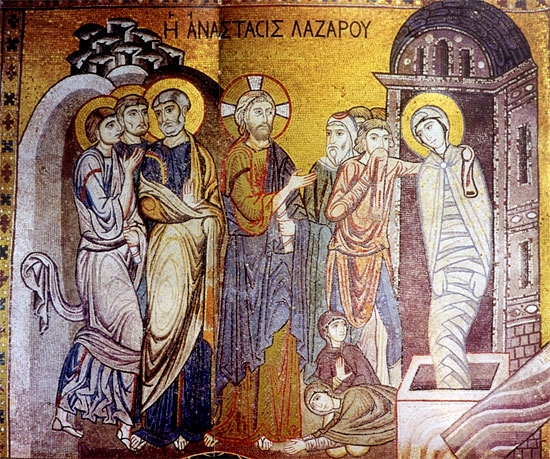

Resurrection of Lazarus

As a feelings obsessed over analyzer, it’s probably healthy that my affinity for answers and explanations has been dulled some. Still though, the fact I equated Lazarus Saturday with but the parish beautification event taking place afterwards, should be a wake-up call. Had my children not asked specifically why the raising of Lazarus from the dead is so significant to us as Christians, particularly right now, only two weeks from Pascha, I most likely wouldn’t have taken the time to reflect a whole lot on the matter. It all comes down to either claiming the spiritual treasures the Church, for two millennia, has mercifully offered our impoverished souls or passing them by. Heaven knows I could use a little encouragement; I’m awfully tired. Thus my choice this afternoon to journey back to that tomb containing the four days dead brother of Mary. What does it mean for me presently that Jesus wept there before defying the natural order of things by breathing life into a corpse? “Come and see!” says the Church. God, help me see more clearly.

It’s probably best to start with this official explanation, a profound one I lifted from the Orthodox Church of America website:

Lazarus Saturday is a paschal celebration. It is the only time in the entire Church Year that the resurrectional service of Sunday is celebrated on another day. At the liturgy of Lazarus Saturday, the Church glorifies Christ as “the Resurrection and the Life” who, by raising Lazarus, has confirmed the universal resurrection of mankind even before his own suffering and death.

By raising Lazarus from the dead before Thy passion, we will sing during the Liturgy of Lazarus Saturday, Thou didst confirm the universal resurrection, 0 Christ God! Like the children with the branches of victory, we cry out to Thee, O Vanquisher of Death: Hosanna in the highest! Blessed is he that comes in the name of the Lord! (Troparion).

So first and foremost, it would seem, the message is this:

Death has been crushed.

Death, and all its finality, has been trampled, vanquished by Christ who is all love, all mercy, omnipotent. This is phenomenal news, obviously. But there is more to the story of Lazarus than just that grand, life affirming, finale. What I’m particularly drawn to currently is the events preceding Lazarus’ resurrection. I am captivated by Jesus’ own emotional reaction to the anguish of Mary and Martha, so convinced by that point all was lost – so heart wrenchingly unsalvageable. Jesus knew that in the end, life would reign, joy would outweigh the sorrow, and yet he grieved before performing that great miracle of miracles. He grieved for his beloved friend decaying in the tomb. And He grieved for us, I’d like to think, all of humanity who must endure great trials, loss, abuse, injustice, as a result of our free will and fallenness – for us who, while on this earth, must fight hard and ceaselessly to believe in what cannot be seen, in a divine compassion we cannot fathom.

I’ll be the first to admit it sometimes seems irresistably easier to just surrender to the despair, or the instantly gratifying pleasures of materialism and the approval accompanying the embracing of worldly priorities and ideals. When you’re exhausted, from day after day battling doubts, struggling against the current, resisting the urge to lie down and allow the fear, resentment, selfishness, hatred (all the vices we as Christians are called to resist) to bury you alive, seizing rest, welcoming help, becomes critical. If I can, with humility, accept my need to be carried along for awhile, by the sacraments of the Church, and the prayers of others, there is hope for me yet. Lazarus becomes then for me a shining example of how to not assume I am ever too far gone for a resurrection, a rebirth – of how to come forth when called, even still wrapped in the ties that bind me, and acquiesce with gratitude to His undeserved grace.

And I will tell first of the beauty I saw in captivity, wrote the poet Irina. That is a war cry against death, despair and hopelessness if I’ve ever heard one! Blessed are they who mourn. Blessed are the meek. Blessed is He that comes in the name of the Lord.

Source: The Self-Ruled Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America

You might also like

Palms in Hand, Pressing on to the Resurrection! by Fr. Thaddaeus Hardenbrook