As soon as you have decided to prepare for Communion, all sorts of obstacles, both internal and external, appear immediately. But they will disappear if you show determination to repent, whatever the situation. Again and again we who are overtaken by idle slumber and are inexperienced in matters of repentance have to learn how to repent. This is the first thing. The second thing is that we have to draw out a kind of thread from one confession to the next, so that the gaps between preparation for confession may be filled with spiritual struggle, determined efforts to do good, which are inspired by the knowledge that a new confession is in the offing.

Now, as ever, we come to the question of the confessor. Who do I go to? Should I keep to one confessor or can I change confessors?

Priests who are experienced in spiritual life confirm that it is better not to change confessors, even if it is only a confessor, and not a spiritual father, who is guiding your conscience.

Priests who are experienced in spiritual life confirm that it is better not to change confessors, even if it is only a confessor, and not a spiritual father, who is guiding your conscience.

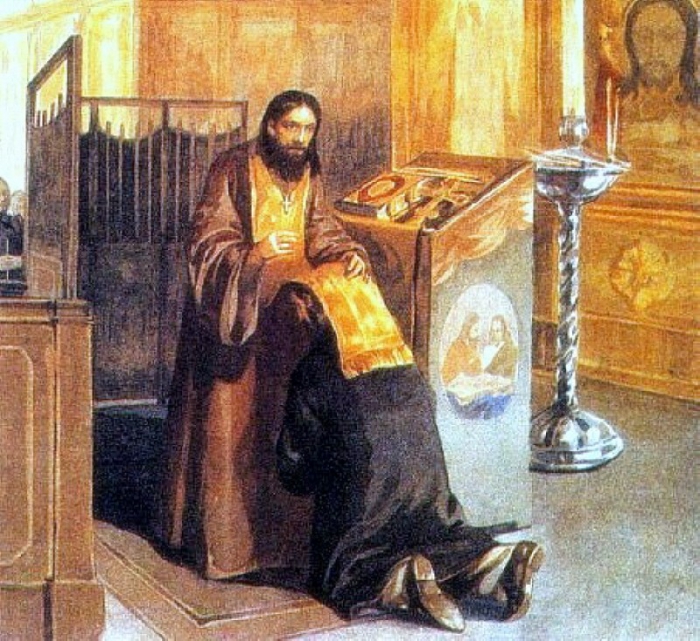

True, it often happens, especially after your first really good confession with a priest, that the next confessions are somehow feeble, cold and shallow, without any great emotions, and then the thought comes to you of changing confessors. But that is an insufficient reason for such an important step. A lack of spiritual uplift during confession is often not the confessor’s fault, but is due to our own lack of spiritual well-being. The best thing for someone who suffers from the disease of sin is to unburden himself as soon as possible from his yoke of sin and receive forgiveness. It is another thing if someone has put aside his personal repentance for his sins and engages in some spiritual conversation at confession or, even worse, engages in talking about everyday life. This is because a talk, even on spiritual topics, can only distract and cool the ardour of the penitent, and it may involve condemning others and so weakens the feeling of repentance. Confession is not a conversation, even about our faults and doubts, it is the burning repentance of the heart, a thirst for purification which comes from the feeling that the sacred is close – the feeling that Christ, the Gospel and the cross on the stand, is invisibly standing next to us – we are dying to sin and living for a new and holy life. Sincere repentance is already the first step in holiness. Coldness means the distancing of ourselves from holiness, that is, dying outside the presence of God.

What should our attitude be to the sacrament of repentance? What is the science of repentance itself?

The first step in worthy repentance must be the examination of the heart. Usually, people who are inexperienced in spiritual life can see neither the multitude of their sins nor the revulsion they produce. ‘Nothing special, the same as everyone else, only a few little sins, I didn’t steal anything or kill anyone’. This is what a lot of people are used to saying. Self-assurance, dryness, irritability, obsequiousness, weakness of faith, lack of love, cowardice, the spirit of complaint, despondency – surely these are not little sins? Surely no-one can say that his faith in God is sufficiently strong, that he has perfect love? That he loves everyone else as his brother in Christ? That he has attained meekness, complete humility, that he is never angered? If not, then where is our Christian life? How can we explain our self-assurance at confession if not as a stony-hearted lack of feeling, as a coldness and deadness of the heart, the death of our souls, which brings ever closer the death of our bodies? Why did the holy fathers, who left us prayers of repentance, consider themselves the first among sinners and cry out to the Sweetest Jesus with heartfelt conviction: ‘None has sinned on earth as I have sinned, for I am wretched and adulterous?’ Are we so sure that everything is OK with us?

The brighter the rays of the sun shine in the basement, the clearer we see the disorder among the various objects there; the brighter the light of Christ illumines the heart, the clearer we see the disorder in the soul, the more we become aware of our sins, the illnesses and wounds of our souls. And, conversely, people who are engrossed in the darkness of sin do not see anything in their hearts and, even if they do see something, they are not frightened because they have nothing to compare it with. Therefore, the most direct path to repentance is in the examination of the heart, cultivating the awareness of our sins by drawing closer to the light of Christ. In order to prepare ourselves for confession, we need to examine our conscience according to the Divine commandments, through a life which is closer to the saints, through certain prayers (for instance, the third prayer at Vespers and the fourth prayer before Communion).

Analyzing our soul, we have to try and distinguish the basic sins from those which are the result of those sins. For example, distraction in prayer, sleepiness, inattention at church, a lack of interest in reading the Holy Scriptures. Do these sins stem from a lack of faith and a lack of love for God, or from laziness and negligence? We should note in ourselves any lack of determination, disobedience, self-justification, intolerance of reproaches, stubbornness, but it is even more important to discover their connection with vanity, arrogance and pride. If we notice in ourselves a heightened care for our outward appearance, the situation of our home and so on, is this not a sign of growing vainglory? If we take our failures in life too much to heart, if we suffer separation very deeply, if we are inconsolably sad because someone has passed on, does this not testify to a lack of faith in Divine Providence?

There is another technique which leads us to the knowledge of our sins; this is to recall what people generally accuse us of, especially those who live alongside us, those who are near to us. Their accusations, reproaches and attacks virtually always have some foundation. What is also vital is mutual forgiveness, in fulfilment of the commandment about forgiveness (Matt 6, 12).

When we examine our hearts in such a way, we also have to be careful not to fall into an oversensitivity or excessive suspiciousness towards every movement of the heart. If we do this, we risk losing the ability to distinguish between what is important and what is not important, getting caught up in petty matters. In such cases the holy fathers advise us to put aside this examination of the soul for a time and go on a simple spiritual diet, simplifying and brightening the soul with prayer and good deeds.

Preparation for confession does not consist of just recalling or even noting down our sins, but of gaining an awareness of our guilt, of raising our sense of repentance to the level of heartfelt contrition and, if possible, of shedding tears of repentance. From here stems the second step which is necessary for confession – heartfelt contrition.

Knowing what your sins are does not actually mean repenting of them. Sorrow for what we have done, tears for sins are the most important thing of all in confession.

But what can we do if the heart which has been ‘dried up by the heat of sin’, is not watered by the vivifying waters of tears? We still need to repent, to repent for our very coldness and lack of feeling in the only hope of Divine mercy. Our lack of feeling at confession is for the most part rooted in the absence in us of the fear of God and a concealed lack of faith or even absence of faith. All our efforts must be directed towards this. This is why tears are so important at confession. They soften our hearts of stone, removing the main obstacle to repentance – the concentration on our egos (Bishop Theophan). The proud and the vain do not cry. Those who do not forgive their neighbours, who conceal evil and offence in their hearts, accusing others and justifying themselves, none of these can cry. What happiness to have tears of repentance! And they are granted to humble sinners.

We should not be ashamed of tears at confession as they water our face. Let our soul be cleansed from foul sin and be clothed in the raiment of innocence and purity.

The examination of the conscience and heartfelt contrition lead inevitably to the oral confession of sins in purity of heart. In this way, we see the third stage in confession – the oral confession of sins.

The holy fathers teach us that we should not expect the confessor to ask any questions at confession, but we should confess our sins ourselves, without being so ashamed that we cannot say them and without concealing or diminishing their seriousness. Confession is a feat of doing violence to ourselves. We need to speak precisely, without covering up the ugliness of the sin in general terms (for example, ‘I have sinned against the Seventh Commandment’).

It is very hard at confession to avoid the temptation of self-justification, attempts to explain ‘mitigating circumstances’ to the confessor, referring to other people, as if they had participated in the sin. All this is a sign of vanity, the absence of deep, personal repentance. Sometimes, in repenting for some sin (for instance, anger, quarrelling), penitents involuntarily fall into condemning others, protecting themselves and accusing others. This is false repentance, it is cunning, hypocritical and displeasing to God.

Sometimes at confession we make reference to a poor memory which does not allow us to recall our sins. And it is true that we often forget our sins. But is this because of a poor memory? Not at all. For example, we know that when we are praised and our vanity is flattered, we remember it for years. But we do not remember our falls into sin. Does this not suggest that we live inattentively and are distracted and do not place any real importance on our sins?

A sign that repentance has been sincere is a feeling of lightness, purity, unspeakable joy and profound peace. On the other hand, unworthy repentance is characterized by a feeling of dissatisfaction in the soul, a special heaviness in our hearts, and a sort of dull, vague feeling of unease.

It must be said that repentance is not complete or useful, if the penitent has not inwardly affirmed a rock-like determination not to return to the sin that has been confessed. But, as some say, how is this possible? Would it not be closer to the truth to say just the opposite – a certainty that the sin will be repeated? After all we all know from experience that in a while we will once more return to the same sins. Following ourselves year in year out, we do not notice any improvement, we take a step forward and then go back again, or, even worse, we take a step forward and then go back two steps.

It would be awful if this were really so. But fortunately, this is not at all the case. There is not a single case where, given goodwill and the desire to correct ourselves, successive confessions and Holy Communion do not produce changes for the better in our souls. But the point above all is that we cannot be judges of ourselves. We cannot speak of ourselves accurately, whether we have got better or worse. Perhaps, a growing strictness towards ourselves and a heightened fear of sin create the illusion that our sins have multiplied and strengthened and that the state of our soul has neither improved nor worsened. Apart from this, through His special Providence, God often closes our eyes to our successes in order to defend us from our worst enemies – vainglory and pride.

Often the sin remains, but frequent confession and Communion of the Holy Mysteries have shaken it and significantly weakened its roots. In any case, is the struggle against sin (perhaps, against its falls) in itself, the sufferings resulting from sins, not a victory? St John of the Ladder says, ‘Do not fear, if you have fallen every day but have not abandoned God’s ways, stand courageously, your Guardian Angel will honour your patience’.

Thus, the science of true repentance can be defined as consisting of the three above-mentioned steps:

- а) The examination of the heart;

- b) The contrition of the soul;

- c) The oral confession of our sins.